First stop: Medieval Jewish Prayer House—Középkori Zsidó Imaház

American historians say Hungary’s political system is dangerous, but conservatives find inspiration in its Christian government. I expected dark shadows in Budapest storefronts, people yearning for freedom. Instead, I found old stones with Hebrew etchings of familiar names, Jewish memory on the hilly side of a fast river.

The fourteenth century sanctuary is small, wooden chairs like sentries, Jewish stars a lattice, like clasped hands linking generations. On a modern Shabbat, old men pray timeworn words.

Ceilings rounded like Jerusalem architecture, just a four-hour flight from Holy Land. I came to Budapest to visit my son. Is it brave to return to the Eastern European killing fields my ancestors fled? My twenty-first century son looks for beauty in its stone streets, but my soul remembers.

Hebrew letters inked onto the plaster in this medieval synagogue: a priestly blessing in David’s shield, Hannah’s prayer arched with an arrow. The bows of the mighty are broken; those who stumble are girded with strength. Red secco ceiling painting discovered during a 1964 restoration. Ancient words evoking an Ottoman siege of the nearby Buda castle. Jews defending our neighbors, desperate to blend.

Everywhere, the color red: in a velvet mantle over the prayer podium, in a drape hiding ancient scrolls. The color of blood, sacrifice, danger, courage. Also, the color of passion, and anger.

This synagogue sits on a residential street behind a typical door, blending into a stucco landscape of sunrise yellow, summer peach, ballet pink. Congregants gather in a cobbled courtyard, too like the hidden coves in this city where Jews were shot. But here, no plaque commemorates the dead, only tilting tombstones bearing familiar names. No stories, only evidence that they lived. It’s a working synagogue come Friday dusk and Saturday dawn, a museum all the other days, paying homage to dead Jews.

We started here on our tour of Jewish Budapest, foreshadowing the story of my people in Hungary: we would visit an equal number of exquisite sanctuaries and cold memorials. To be a Jew is a pendulum-swing existence, a constant living in extremes, a balance of horror and beauty. In this city, I ate matzoh ball soup and goose-stuffed cabbage in fashionable restaurants with names like Mazel Tov and Rosenstein. I clapped at a klezmer concert on a Friday-night stage in the most cosmopolitan district. As if we had made it into the popular culture.

One day, an old lady on a tram said she preferred Hungary to the United States. Hungarians believe in God, she said, and Americans love money. She studied economics in Washington, DC, when she was young. Now eight-five, she’s at home in her authoritarian country. This place brings her comfort, but I couldn’t wait to leave. My son appreciated the public transportation, and how cheap everything was. A country in flux: absolute adherence to rules, and short supply on everything.

I came to Budapest on Election Day in a midterm year, wanting to avoid the results, for fear of extremists erasing democracy. But I couldn’t escape. I landed in Europe to scrolling headlines: extremism defeated by candidates preaching justice for all. I settled into my seat and eased into a dreamless sleep.

Second stop: Shoes on the Danube

Thick boots, simple pumps and baby tie-ups bolted into concrete. A memorial of a moment, of Jews ordered by Nazis and eager Hungarians to step out of their valuable leather and wait for the bullets to kill them. Men, women, children, lovers, friends, families, shot, their limp bodies falling like dominoes into cold water, floating away in a red-stained river.

A bronze plaque, flush against the concrete, reads: to the memory of the victims shot into the Danube by Arrow Cross Militiamen in 1944-45, erected 16th April 2005. They were Jews, damnit. I want to scream into the open sky. A cleansed message with no mention of the reason these precious people were murdered. Gunned down, one after another after another falling limp against the cold and lonely earth.

This famous memorial sits in the shadow of the Hungarian Parliament, politicians just out of sight. You have to know the site is there to find it, descend wide steps toward milky-gray waters. No signs lead to horror.

In the rainy cold, squirming teenagers and barking teachers shuffle past the shoes. Are they oblivious because of their age or because they’ve consumed too much harsh memory? Do they even know the truth? Who does their teacher say died here, and why?

I wait for their noise to dissipate before kneeling, hot tears on wind-cold cheeks.

It’s not hatred that kills good people. It’s the not-knowing what to do with difference.

I would never vacation in an authoritarian country. But my son was studying math education in an old building with a Jewish star in its courtyard. So I slept in a nice hotel in the heart of a bustling city and tried to see past conflicting histories. Nothing screamed fascism. I never saw Viktor Orban and found the Communist ruin bar sort of hilarious. I could almost believe in safety.

Third stop: Monument to the victims of the German occupation by Péter Párkányi Raab, Szabadság Square

An eagle representing Nazi Germany beside archangel Gabriel, Hungary’s patron. Isn’t the eagle a symbol of American independence? And Gabriel a Jew? Of course, the eagle is a predator, soaring above all other life, eying prey with precision, swooping in unannounced.

The words, remembering the victims in Hungarian, English, German, Russian, and Hebrew. The real memorial is just in front of this, wind-flapping pictures, handwritten notes, melted candles, and old suitcases. And the concrete monument never mentions how eagerly Hungarians rounded up half a million Jewish neighbors for slaughter.

Ever had a dream you couldn’t wake up from? You kick and flail in the muted night, claw toward the surface of awakening, but lay prone, heart thick with thumping. It’s the Holocaust for me. I can never escape it, and I don’t want to because it’s become ok again to openly hate Jews. When I was young and single, I dreamt they were banging at my door in the dark night. I woke before they pushed inside, but kept a hammer under my bed, just to be safe.

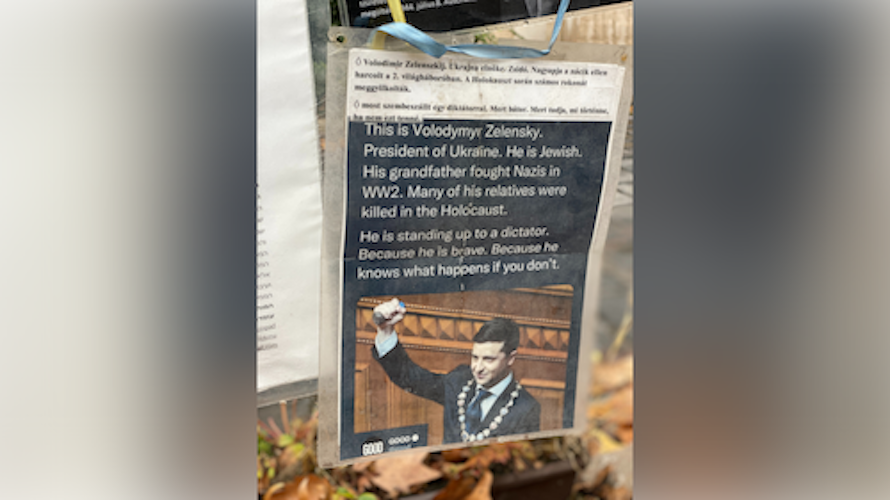

Photos dangle from barbed wire—a little girl in a tutu, a family of four headed to Auschwitz, the words: anyone who denies the crimes of the past is ready to repeat them anytime. An old cracked suitcase, a mangled black shoe. A sweet picture of an older boy and his doting sister, cheek to cheek. Chiding comments by woke Hungarians, blaming their government for the slaughter of my people. A chilling photo of an old man with a cane, his shadow a family of four holding hands. An image of Volodymyr Zelensky, the Jewish president of Ukraine, fist raised, a slight smile on his young face, and the words: He is standing up to a dictator. Because he knows what happens if you don’t.

I never used to vote in midterm elections. In the 1990s, it was just something we didn’t do, complacent in budding careers and big-city living. Too busy loving the freedom of being American, believing we had it all.

When I turned religious and married a conservative man, I awakened. Our votes canceled each other out. I left him before another election came round, but in 2016, screens turned red with American fascism. We might have to move to Canada, I texted my thirteen-year-old daughter, who was at her father’s house on Election night. My ex emailed at one in the morning, what the hell are you saying to the children?

I’ll do anything to protect my family. I’ll do what it takes to keep us alive. This is Germany in the 1930s. They always come for us. Again and again and again.

Could I have prevented the fall of America in the twenty-first century by voting in the twentieth? Did my adolescent indifference pave the way for fascism? How stupid I was to take freedom for granted, to give it all away.

Fourth Stop: Klauzal Ter., “You shall tell your son . . .” Exodus 13:8

The streets of Budapest are like spokes on a wheel. I was constantly confused by courtyards and alleys, old buildings with the memories of people running for their lives.

In the midst of twenty-one Michelin star restaurants, high fashion boutiques and gleaming hotels, sits a quiet courtyard where people leave pebbles on a plaque. “You shall tell your son . . . “ Exodus 13:8 Another place Jews were rounded up and killed. Late fall, the leaves have fallen off two scraggly trees; the ground is cold. This is the third place today where Jews were murdered. I’m bored by repetition, like those teenagers on the banks of the Danube.

Tour groups crowd in to see where Jews were killed. An Italian explains the site. Then a Hebrew speaker. Above the memorial, red flowers on balconies are not yet winter-wilted. The patchy plasterwork of this building conflicts with a smooth new hotel next-door. Horror and beauty are bedfellows.

Viktor Orban rode financial turmoil to power. Now, he’s stacked the courts, claimed the media, created an “us or them” rhetoric—real Christian Hungarians versus immigrants and Muslims and gays. Jews are too small in number to matter. History saw to that.

What authoritarians do really well is make us afraid. But we are to blame for their rise. When they care more than we do, we get what we deserve.

There’s a woman trying to reclaim Hungary: Katalin Cseh, a twentysomething leading the third biggest political party. We needn’t choose between identities, she says. We can be everything all at once.

If the twenty-first century is about identity, who do we want to be?

Fifth Stop: Kazinczy Street Synagogue

Built in 1913, with pale blue walls, gold metallic stars of David and flower-shaped stained-glass windows. I’ve seen the Holocaust sites, and now I step inside a gorgeous synagogue. There’s seating for women on the second floor, hard wooden benches for the men on the first, everyone facing the Ark and its holy scrolls. Only seventy parishioners regularly pray in this echoing sanctuary, in the same neighborhood where the young go at night, to ruin bars and raving restaurants.

A wedding song etched in metal: kol sasson v’kol simcha, the voice of joy and the voice of gladness. Jewish stars in glass and metal, wood and cloth. An art nouveau tapestry of identity. Sunlight filtering through skylights.

There is light everywhere, bright and shining. All the detail and thought that make a space holy. Beautiful, I say. Yeah, but I came on Rosh Hashanah and there were only a dozen old men, my son says.

After college, I lived in Washington, DC, the air thick with humidity that peeled back the paper covers of my favorite books. It’s not easy to live in a swamp, even if it’s paved over with concrete and plaster.

Every city has a story, and versions vary between storytellers. In Budapest, a soaring synagogue tells me Judaism is accepted by all. But then I pass another plaque commemorating death. No memorial says the word Jew, not one expresses remorse or lament or even temporary sadness. It happened, so a story is told. We consume the words and keep walking.

Sixth stop: Rumbach Street Synagogue

Minaret towers and Moorish Alhambra columns, this place once drew Jews looking to reform old ways. Today, it’s a concert venue and a museum.

A black stage fills the sanctuary. Circular windows with orange and turquoise flowers in the glass. A gold-etched, domed ceiling. Heavy lights hang low, to illuminate the performance. A gaudy gold Ark. So many conflicting details. I don’t know where to look first, or last.

Built in 1872, Jews worshipped here until it became a Holocaust deportation point. Then the Soviets came. Jews only returned to the crumbling façade in 2006, staking claim over decades of decay. Birds had flown in through holes in the roof, built nests in the sanctuary. Now, nonprofits and charities inhabit upper-floor offices. An exhibit on the third floor details the history of Hungarian Jewry, through stories of the Pulitzer family. Jewish integration is everywhere. Come quick and take your seat. The show’s about to begin.

Seventh stop: Dohány Street Synagogue

The largest European Jewish house of worship, the second largest synagogue in the world. Three floors for worshipers. Flags indicating the languages of visitors. It’s so big and overwhelming that the rabbi must climb to a podium suspended above the first floor to be seen and heard.

I couldn’t worship here. Too ornate, too big, too much of a show. Jews on display. I’d feel lonely. And I want to belong.

On the street, authoritarianism doesn’t look different from democracy. The buildings are old and spackled, with exquisite frescos and metalwork. At a selfie store, employees wear pink, next to a Burger King, and buses and trams come frequently with an app that tells you in real time how long you’ll wait. People hustle along. Little cars drive fast. They won’t stop for pedestrians, so look before you walk. Restaurants and cafes and bars, down narrow lanes, tuck into significant buildings, new life in old spaces. Across the river, as the craggy hills rise, people go to school and work and buy a kebab at a kiosk and pull coats tight as the winter wind sweeps down from tree-heavy hills. In subway stations, bakeries sell hot dough rolled in cinnamon and sugar and nuts. Sometimes, the sun shines, and the early mornings are cold, but people walk fast and smoke cigarettes in cafes with tiny cups of espresso.

Budapest looks like any place. Men wear the same tapered jeans as any European city, have the same haircuts. On the bus, all the shoes are black, and the people smile when you stand near them, gripping the pole for balance.

Final Stop: Bethlen Gábor tér 2, BSME Building

The building where my son is studying used to house the National Institute for Jewish Deaf-Mute. Built in 1876, it expanded to include a synagogue in 1931. Before the Jews were rounded up, it was an elementary school and headquarters for various Jewish organizations.

In the courtyard is a memorial: a bronze tree between narrowing walls of rocks contained by wire. The focal point: a concrete Star of David. All I can see is the wire keeping the rocks from tumbling down and burying everything.

There are no waves on the Danube. The water is milky gray and flat. Hungary is land-locked with only one river bending through the countryside. No easy way out.

I have circled the globe, adjusting to time zones and elevations. My son and I climbed to the highest point in Budapest. Midway, he scrambled up a sheer rock face. Careful, I called. Don’t lose your footing. Please stay safe. At the top, the sun shone without interruption.

One night, my son played a piano in the rail station. The click-click of heels on marble beat a dull rhythm as his fingers flew over the ivory and a beautiful melody lifted to the high ceiling and out onto the tracks and through the open doors and over the wet pavement in the dark night. I was naïve to believe extremism lived abroad, to think hatred was an old story.

Authoritarianism is defined as favoring complete obedience or subjection to authority as opposed to individual freedom; exercising almost complete control over the will of another. I had no control over where my son studied, and I wanted him to know the world. I’ve never been in a place where the Holocaust actually happened, he said when he landed in Budapest. I spent a half century avoiding it.

But we go where we are called. After the hike, drenched in exertion, we ate hot dogs and hamburgers and salted fries in the café on the mountaintop. Then, we rode the chairlift down, tired from the enormity of it all.

Lynne Golodner

A former journalist, Lynne Golodner is the author of eleven books and thousands of articles and essays. With an MFA from Goddard College, she lives in Huntington Woods, Michigan with her husband and a rotating combination of her four kids. Lynne works as a marketing consultant and writing coach, helping authors build brands and market their books.