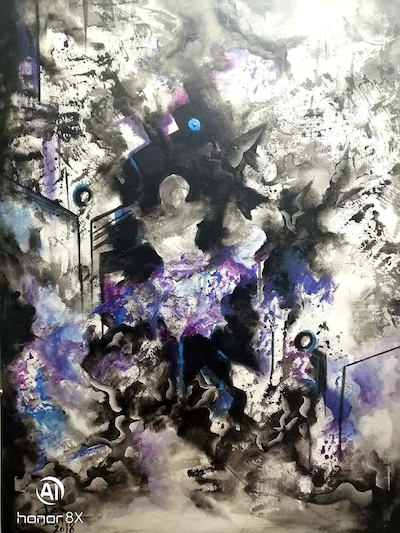

Infiltration by Asmaa Samir

Editor’s Introduction: Written by Elham Al-Zubaidi—and translated by Amir Al-Azraki and Sharon Findlay—“Camp Seagulls” makes a necessary contribution to Arab women’s literature in translation through highlighting lived experiences of Iraqi women, who must bear the burden of a continued war and the presence of ISIS. “Camp Seagulls” is an auto-fiction, based on actual events and real people whose names have been changed to protect their identities. This text draws from Al-Zubaidi’s notes taken during visits to IDP camps as part of her work as the director of the Lotus Cultural Women’s League. Portions of the text are followed by brief readings in varying languages by the artists, scholars, and writers Elham Al-Zubaidi, Tamara Alattiya, Thawra Yousif, Aruba Bayazed Esmail, and Souma Kaabia.

When confronted with real pain one must be willing to hear the irrational.

Our tires plunge through deep potholes filled with yesterday’s rain. The driver cuts sharply to the right in the direction of Khamsa Mil IDP camp located in the northern-most part of the city of Basra. He curses the miserable road conditions under his breath.

Fairouz’s melodic voice emanates from the car radio: Enough! I tire of blaming and my body withers.

What beautiful memory inspired this soulful refrain? I wonder, wishing that Fairouz’s song had the power to transport me to the countryside of Damascus . . . the tune fades, and my musings dissolve as well, replaced now by the words, phrases, and memories of displaced women whose stories I have faithfully recorded in my notebook:

Mariam and her three children are allocated, by the camp, a small room. In strange contrast to their grim surroundings, bright floral designs adorn the mattress upon which her children now sleep. A flicker of a smile appears as she recalls her husband watering similar flowers in the garden of their home in the countryside . . . she can visualize him there so clearly. Tentatively she extends a hand in his direction, willing this moment to last longer, before he is swallowed up by the harsh darkness of her room.

Fairouz begins another song.

The urge to cry nearly overtakes me as I draw in a deep breath and fix my gaze out through the rain-streaked window. Sabirah, the volunteer doctor seated on my right, looks at me with concern. Are you okay, Elham? she enquires gently.

I don’t know, I whisper.

Turning partway around in the front passenger seat, Qadir, our colleague, remarks over his shoulder, She would be better if she broke her pen and destroyed that notebook of hers. His flippant remark somehow momentarily breaks the tension, and I smile grimly in spite of myself.

The road seems endless, choked with traffic. Noisy vehicles heedlessly splash the filthy water and muck everywhere under the miserable grey sky.

I catch myself contemplating how my perception of rainy days has changed. There was a time when I enjoyed the wet grayness washing everything clean . . . today, I respond with different emotions. Why does this weather make me so sad? I shiver and feel hot simultaneously. Maybe I’m coming down with the flu, maybe that’s why it all feels so ugly and distorted. A poem comes to me, which I record in my notebook:

And I repeat in my silence,

When rains pour from the sky

My heart pours with tears.

Others mistake

That what is happening on my cheeks

As rain-drops, not tears

From a broken heart.*

*Drawn from Elham’s poem, “Hamasat Shajerat al-Jowz” (Whispers of the Walnut Tree).

The car halts at a red light. A small figure stands on the street corner, a child begging in the rain. The foggy, streaked pane does not obscure my view of her face as her eyes fix desperately on my window. She watches intently for any sign that someone may offer charity, and steps off the curb toward our car. The driver hollers at her to stay out of the way. The light changes and we begin to move. On the other side of the street, I glimpse a woman in black, splattered with mud. Twisting in my seat, I try to get a better look out the rear window as we pull ahead. Is it possible that she has escaped the IDP camp in Baghdad only to end up begging on the street here in Basra? Or is she simply one more old woman, like so many others, who carries the same pain, the same burden, and the same loss?

Rashida was in her sixties. Her pale strained face, the mud spattered on her clothes and the impatience in her eyes, told a thousand stories. I met her in the IDP camp in northern Baghdad. Rashida would walk back and forth repeating her story to everyone who would listen. That day, at dawn, I was stoking the mud-oven to bake bread as usual . . . when I heard voices getting louder and louder, blaring from the speakers on their cars that came bearing down on us. Black banners blotting out the brightness of the rising sun. Through megaphones, they ordered everyone outside. “Do not carry anything but the clothes you are wearing.” They assembled us in the town square where we were lined up before them. First, they took all of the young men then they ordered them all into the mosque, my two sons among them. With relief, I believed that surely the holy books of God and the prayers of so many devoted people would protect them in that mosque . . . I said to myself, I can die happily now knowing my dear sons are safe in the house of God. But suddenly the minarets of the mosque flew upwards as the building collapsed and fire consumed everything. They would not let me search for my sons among the ruins and rubble. I hope that the holy books saved them. My father told me that fire cannot consume holy books. They didn’t let me search in the rubble of the house of God.

Enough! by Elham Al-Zubaidi

Enough! by Elham Al-Zubaidi

Excuse me, Cicero, but your famous proverb, Inter arma enim silent leges or In times of war, the law falls silent, is sadly inadequate. Where weapons are concerned, not only are laws silent but so too is the human conscience. Even God is resoundingly silent.

I am haunted by my memories. Why do I recall these accounts so vividly? Cursed memory . . .

Our car arrives at the camp gates. I am jolted out of my recollections and back to the reality of guards at the car window.

They are asking for our permits, our reasons for entering, documents, IDs and so many questions. As usual, we parrot back our routine replies: we are a volunteer team from Iraq Foundation, we have a female doctor with us to examine and treat female patients in the camp because a male doctor runs the health center and female patients require a female doctor. It feels clichéd or farcical that we are forced to repeat these explanations even though everyone knows our reasons thoroughly by now.

As we wait at the gates for the authorization to enter, a guard asks, When did they tell you that they needed a female doctor? It’s always the same.

Dr. Sabirah whispers impatiently in my ear, How much time will this take before they let us in? She asks this rhetorically because the ritual has become so predictable to all of us.

Eventually, in their own time, the guards allow us through the gates.

Time. In a church, just a few days ago, I was struck by the word time as articulated by Bashira, a Christian refugee:

Don’t tell me about my rights, or UN Resolutions, and or what we need. I don’t understand the things you’re talking about in this workshop and I really don’t care. Instead, tell me when it is time for us to go back. Just get me back to Nineveh, to my home where I lived for fifty-three years. I want to clean it and prepare food for my children and grandchildren. Water the garden, do the laundry, iron, clean the dust from the pictures, bake and then send some to my neighbors. I want to light a candle of gratitude by my statue of the Virgin Mary, which was a gift from my uncle. Her holiness stands in the middle of my house with fresh flowers, candles and incense at her feet. In the evening, I sit on the swinging chair in the garden and complain of my daily tiredness to my husband. He smiles gently and erases my fatigue with his words: “May God keep you, protect you and never take you from us.” Then I get started on dinner . . .

I wanted to cry on Bashira’s shoulder. I so wished that I had an answer for her. I wondered how I could tell her that her situation today is better than that of Aunt Josephine whom she may know . . .

Shall I tell her or leave her dreaming of return? I asked myself. Better to leave her with her dreams.

How can I avoid the memory of the church in Sheqlawa and of Rita who escaped by a miracle with the rest of her family members? They fled with their widowed neighbor, Aunt Josephine, whose grown children had moved away, leaving her all alone, but for the grave of her husband, in Nineveh. How could I wipe Rita’s tears from my memory as she told me the story of Aunt Josephine?

Sitting in a corner of a former classroom in the camp that has been allocated for five families, Aunt Josephine, sixty-five years old, unrolls her pain on the bare ground. She draws a cross on the wall and lights half a candle that she has carried in her pocket since her last devotions at the Church of Sheqlawa. After being ordered to leave her house and everything behind, she managed only to bring this single candle stub. In Khamsa Mil camp Aunt Josephine closes her eyes to pray, to make a proper petition to God, but finds herself unable to remember a single word of the prayers she has always know. She abandons the effort, which is too much for her overburdened old heart. Aunt Josephine has one simple request to beg of God before the light of her candle expires. A single tear rests under her eye without sliding down her cheek. As the candle flickers dies into darkness, her final wish is granted, her last breath released, as she passes on.

Alienation by Asmaa Samir

Alienation by Asmaa Samir

Having proven to the guards that we are not terrorists, we are finally given their blessing, and the gates of the camp open before us. Now we can continue to the medical center where crowds of women and children await us.

Just leave your pen and book, Elham, Qadir urges. Don’t take any notes today; surely you have enough collected from what you’ve taken down over the past year. Perhaps he’s trying to be helpful. I smile at him; he well knows that I am not about to follow this advice.

Women and children shove against one another in their hurry to enter the medical center of Khamsa Mil camp.

A sobbing woman, whose voice quivers with grief and fear, calls, Please, doctor, try to stop the bleeding. I don’t want to lose this baby. He is all I have left of my husband whom I lost with one stroke of the blade. With him I lost my dreams and hopes. I couldn’t carry with me our beautiful bedroom . . . the orange curtains, the clothes I wore for him, our wedding picture. She appears to be five months pregnant.

Turning toward Qadir with a sigh, I remark, Is this the type of story you think I should turn my back on? Looking again at the pregnant woman, I attempt a reassuring smile but feel ridiculously inadequate to provide any actual assistance.

The pushing and shoving of these women and children, desperate to see the doctor, continues.

Another woman, dressed in black, grabs my attention. She’s lying on a stretcher. I overhear the doctor giving her the news that there is a tumor in her breast. Further analysis at the hospital is required. She receives this bleak prognosis with delight and asks if the tumor is fatal. She hopes it is, so that she may join her children and husband without committing the sin of suicide. Her obvious joy at the prospect of death shakes me to the core and I recoil. I withdraw to sit on a nearby bench just to process my own turbulent emotions. The specter of cancer is transformed into a source of comfort, of solace, for this woman. To her, death is a preferred replacement for life, and cancer becomes the life raft to which she clings when all she has ever known and loved has been washed away by a tidal wave of devastation. I cannot cast her twisted visage from my mind no matter how hard I try.

Being a receptive and careful listener invites people to pour their grief into you but, when they leave, their stories remain. This is what I am now accustomed to, and these women seem to intuit that I am such a vessel who willingly receives and holds what they have to share. They do not, and cannot, see its impact on my soul.

I notice a few women have observed me on the bench and are moving in my direction. One, clad entirely in black, approaches me. It seems that black is the constant unrelenting color on those bodies. I rarely see women wearing anything else other than black. They are clothed in profound sorrow.

Don’t be surprised by what Um Shamil said. It takes me a moment to realize that the speaker is referring to the woman with the death wish whom I have just seen on the stretcher. Sometimes seeking death is much better than life because it puts an end to torment. Do you know, Miss, when my neighbor called me to tell me that they had beheaded my husband and hung his head on the fence at the local police station, because he was a police officer, I did not cry for days. But when I remember my Christian neighbor, who sang sweet hymns every year before their feast, I break down, I collapse into tears. The only reason I do not wish for death is because of my remaining children, not for lack of suffering . . . death would be a sweet release.

This refrain is taken up by another woman, who sits nearby and idly plays with a stick.

I am jealous that you still have tears. My tears dried up the day I left my house on the banks of the Tigris in Nineveh. Now when I cry, I do so without tears. My sons are not dead, and my husband fled with me here, but my heart lives in Mosul on the riverbanks, and I mourn the death of my heart.

A Shabaki woman, overhearing the conversation and observing us with the eyes of a ravenous eagle, shouts over everyone,

What is the purpose of your crying? I have lost ten members of my family. My young sister, whose beauty we envied, was taken captive; my oldest son stayed and fought by his father’s side until both of them were killed. My brother was beheaded. My house became a pile of ashes, and my daughter consumed by leukemia. Don’t tell me about crying for it can never express the magnitude of our pain. Find us something greater than your crying, a cry equal to our suffering to make those black banners tremble with shame!

Yes, with shame. Once again, the present carries me back into a memory. Suddenly I am back in Erbil and a Yazidi fighter is telling me her story.

We no longer feel ashamed before men, because we became like them. We climb mountains carrying weapons, we fight under the cover of night. Even though I am proud, I am sad because I have forgotten that I am a woman. I miss that femininity in myself. I lost her since becoming a fighter. She left me when I left Shankal and I don’t know, even if Shankal returns to peace one day, whether she, my femininity, will ever come back after I have killed so many men of the black banner.

Body Hymns by Asmaa Samir

Body Hymns by Asmaa Samir

Qadir gestures towards us. He wants us to move aside so he can take pictures of routine procedures, and document the condition of the medical center. I take a walk. Who knows where my compass of pain will direct my steps.

A child peeks from behind his grandmother’s black robes, gripping her legs for safety and protection. His eyes dart about the courtyard, fearfully alert to danger. This is Ibrahim who is six years old.

He fled from their village with his grandmother and his wounded, bleeding mother. The three of them walked along countless dusty roads. Ibrahim took upon himself the task of being the lookout. As his grandmother and ailing mother pulled him ahead, he constantly checked behind to see if the black banners were following. His mother did not survive. They buried her in a cemetery en route, and Ibrahim and his grandmother continued. The need to maintain his position as sentinel for his grandmother, even here in the camp, has not left him. Clinging to her skirts and looking behind them, he is always alert to any threat.

While I cannot recall her name, I will never forget the words of the woman who said, I dream of the day when innocence is restored and children ask their mothers, “What was the war like?”

I dare not tell her that this day will never come to us in Iraq.

If I were to draw the face of Ashi, how would I depict her distraught features, those of a desperate mother in search of her daughter?

Ashi intercepted a journalist who was accompanying our team through the camp, insisting on giving him a photograph of her daughter and begging the newspaper to publish the picture and write about her missing child. “Please write that she is a young woman the color of flowers, with eyes like turquoise stones, and brown hair and a child’s smile. She was a top student in school and dreamed of becoming a doctor for our village. She wanted to invent a medicine that would not taste bad instead of the injections that always make the children cry . . . find my girl!

Across the compound, a group of refugees and activists gather around a religious cleric giving a sermon. He urges the congregated people to have patience and pray with him.

The shrill voice of one of these displaced women rises above his monotonous droning.

She shouts, Excuse me, sir, I once knew patience. As for praying, it has been a long time since I could remember the words or how to speak them. Her raspy voice penetrates the soul directly, bypassing the ears. I turn to her, meaning to say something but I hesitate, self-conscious before her raw pain. She leaves before I can say a word. I respect her need for distance, solitude. But the cleric pursues her, trying to entice her to join in the prayers. His efforts are in vain. She takes no notice of him, her heavy steps loaded with her misery. She disappears. I wish I could have said to her, You’re right, dear, about so much that has been forgotten. We have lost our way to many things, and much has been lost completely.

I wish I could have told her that she’s right not to allow the smug preacher to smother her fire with futile prayers and platitudes. And I fervently wish for the power to lead this cleric by the hand, walking among the Yazidi women and hearing their stories. Maybe then he’d understand how shallow and irrelevant his pretentious advice to have patience sounds. If he would look at them, I swear I would tear out the pages from my notebook and place them in his hands. He could read them in place of his precious scriptures, and learn about these women’s pain and loss!

A Yazidi woman, Arjin, climbing the steep mountains behind a group fleeing for their lives, vainly tries to keep pace with the others while pulling her stumbling and heavily pregnant daughter by the hand. She urges her forward, desperate to keep up, hauling her poor girl along. When the labor pangs begin, her daughter involuntarily screams in agony. Their pursuers of the black banner hear and intercept her cry before it can reach the ear of God. Moments later, headlights bear down on Arjin and her daughter, then the men emerge like shadows from their cars with their filthy beards and revolting black banners. As they approach, Arjin positions herself between them and her daughter, trying to protect her daughter, imploring them to have mercy. The men reassure her not to worry, only seconds before they the tear off all of her clothing and rape her on the spot. The cruelest black banner brute crouches over Arjin’s laboring daughter. I will help you give birth, he says crudely, before raping her mercilessly. After that, they all take turns with her. In the end, they leave Arjin’s daughter close to death, pregnant, her child smothered in the womb, her flesh ripped and torn . . .

I would tell the cleric this story.

I wish I could tell him that even heaven itself is ashamed of the grave of Hayat, of life’s forgotten tomb.

Hayat was the youngest. She slipped off her father’s shoulder while they climbed the mountains, fleeing the black banners. He had been holding her on one shoulder, and her older brother on the other. Hayat fell, rolled down the hill. When her head smashed on a rock, she was killed instantly. She was buried right there, underneath the very rock that had ended her life. Her father carved the following words into it: Here lies Hayat (life), and we proceed towards death.

Transcendence by Asmaa Samir

Transcendence by Asmaa Samir

I move away from the sermon coming from the loud, dispassionate, soulless voice of the cleric. I do not want to hear him. A nearer voice seizes my attention. It is Sana’s. She is speaking to me with sad sunken eyes.

That evening, when that monster tore my clothes to pieces, all prayers were shattered and the heavens became starless. I do not think there is a punishment in earth or in heaven that is equivalent to the crime of rape. Sister, let me give you some advice. Leave off lecturing about human rights and the United Nations’ Resolutions. These do not in any way decrease our suffering. How do your articles and agreements help us? Just forget that nonsense.

I return home and take a hot bath. My mother has prepared a warm meal. Yet, these comforts are unable to restore any sense of balance or wellbeing. Fatigue and hunger appeased, I find that I am in still in need of something, of what I am not sure. Maybe I need to forget, or maybe to scream. I wonder if playing with children would divert me as it usually does . . . no, I need something wild, to break free of horror, to rid myself of the oppressive pressure in my chest.

Visiting day at the IDP camp is over for the week, but the stories and faces remain indelibly fixed in my memory. Ghastly images, that have been shared, jump about in my brain, which flashes from scene to scene. The women’s stories visit me with vivid and obscure details, accompanied by the smell of death and gunpowder, summoning me to write, to draw, to record them all, but this urge clashes with my feelings of disgust and the need to weep. Sometimes I wonder what I should do with all the voices, the anecdotes, and the tokens of terror that fill both my head and my heart.

When one becomes a vessel of such horror, it is hard not to turn into a barrel of dynamite: reactive, explosive, and easily triggered even by a child when he persistently demands that you come to play, and tosses his ball in your general direction.

My nephew’s red ball, thrown light-heartedly in my direction, shoots across the room. Its impact is like the spark that ignites my grief. Tears well in my eyes and spill down my cheeks. The poor child is alarmed by my raw emotion and tears. His only crime is being playful. I have cruelly crushed his innocent attempt to engage his aunt in a game. Immediately filled with regret, I apologize and take him up in my arms, murmuring words of reassurance.

It is not my nephew’s fault that the ball he tossed struck another wretched memory to the surface of my disordered, fevered mind. It is Ahmed’s story that haunts me now.

His foot freezes as he is about to kick the soccer ball towards the other children in the camp who have dragged him outside to play. Suddenly, overwhelmed by terror, he begins to shout and scream at the other children to stop their game. He turns aside and vomits, then wails loudly, Ah ah, they are kicking the head of my neighbor’s son, Saif. He was only teaching me to play soccer. I just wanted to be as good as he was. Ahmed was a ten-year-old who loved soccer; his neighbor, Saif, a seventeen-year-old, was a role model to him and a very good player. Saif had dreams of one day playing for the national team. But because he made the mistake of wearing a Barcelona jersey, the black banners took him for an infidel and put an end to his dreams and his life. They said the color red was forbidden and his love for soccer meant he was corrupted. Saif’s punishment for wearing the wrong clothing was to be beheaded in the town square. To add insult to injury, the filthy black banners then played a gruesome game of soccer with Saif’s decapitated head.

Climbing into my bed, I hide under a blanket, desperately seeking safety and comfort. I am just beginning to drift off when I feel a gentle hand waking me, offering pills and a warm lemon tisane. I attempt to open my eyes to see who it is but they ache painfully in the harsh lamplight and I squeeze them shut again. I catch a brief glimpse of my sister standing over my bed. Slowly, I become aware of strange sounds. Someone is sobbing in the distance. Where is the sound coming from? I hear my sister’s soothing voice, You’ve been crying in your sleep, Elham. With relief I realize that I am safe at home, and not in the camp anymore, not near the old man who has been stalking my dreams.

Day after day an elderly man sits in the corner of his tent. His moans and sobs fill the air as he laments the death of his dear son and daughter-in-law. My son, Darwish, had dreams with his beloved Jian of making their home into a paradise. He didn’t know that hell was waiting for both of them right here on earth. Oh God! Jian was viciously raped, and my son Darwish beheaded in front of what remained of her. I ask myself, why did God let me live? This will be my question until my dying day, and I will not stop asking, I will not relent until He answers my question. Why, God, why? I have been your loyal and faithful servant all my life, so why, why? Is this how you reward me? Answer me! Why?

Maybe the luck of Shukria was better than Jian’s. For the first time, Shukria felt that the universe was not being so unfair to her.

When the savage black banners gathered the “beautiful” women of the village, she thanked God because she was ugly and short and dark. However, Shukria did not escape unscathed, for they kicked her around like a ball, and whipped her for wearing the color pink. She withstood the beating until she could no longer feel the blows or the pain. As the day ended and it grew dark, they discarded her in a heap of corpses. Her grandmother’s dead body was lying above her. Someone came to Shukria’s aid, pulling her out from beneath her grandmother, and then the rescuer ran by her side through rough roads to join the survivors. They fled towards the mountains but as she scrambled up a slope, she looked around for her savior only to realize that he had disappeared.

Captive by Asmaa Samir

Captive by Asmaa Samir

With difficulty, I swallow the medicine offered by my sister and drink the warm lemon tisane. Her ministrations are comforting. I am prepared to attempt sleep once again. As she tucks me in, I ask her to turn off the lights, and my phone as well, before she leaves me alone. Bright lights cut through the drawn curtains and into my room’s semi-darkness, illuminating parts of it erratically. My own cries wake me over and over again. Fever paralyzes my body and, even though I crave deep restorative sleep, memories and stories wash over me, holding me in the dark, preventing me from drifting off.

Women’s voices.

Children’s screams.

The caravans of the camps.

The minaret tower of Jonah exploding into the sky.

Images of explosions on newscasts.

Cities in ruins.

Cries of mothers.

The sinking of refugees.

Rapes of children.

Beheadings.

Doors of Christian’s houses marked with N.

The selling of Yazidi women in slave markets.

The black banners.

Distribution of medical aid.

The epidemic of diseases.

Low supplies of chemotherapy medicines.

The cackling of politicians.

Crying children.

United Nations’ Resolutions.

The extended hands of the poor.

Mud pools in the streets.

Black clothes for every size.

Piles of garbage.

Cables of power generators crisscrossing the streets.

Rising temperatures.

Decreasing petrol prices.

Songs of war.

Screams.

The funeral rites of heroes.

Sounds of destruction under the axes that destroyed the Winged Bull.

The crumbling of statues.

The beating of hands on chests.

Protests and demonstrations.

The spread of drugs.

Divorced women.

Undocumented refugee mothers and children.

Legal clinics.

Workshops.

Lectures.

Item 1325 of the UN Resolution, promising women’s freedom.

Screaming.

Pain.

And, and, and . . .

My failure to be a savior fuels my attempt to be of service to at least a few. I am a listener to the fears and grief of the wounded and dispossessed. To actually rescue anyone is impossible in a country where the march of war is relentless.

Feelings of despair and uselessness can push one into a deluge of daily anxieties and apprehensions.

My fever is getting worse. My breath is getting heavier and more labored beneath the blanket. I wish I could scream for help but my voice is suppressed deep inside me. There’s nothing to do but wait for someone to open the door and relieve the suffocating darkness. But I asked my sister to leave me alone. I also rejected Qadir’s advice not to write down all of the stories in my notebook . . .

Months pass, and the sun sets in Elmaghrib as the call to prayer sounds over the loudspeakers. It is time to break the fast on the first day of Ramadan . . . I receive a phone call from the IDP camp. A refugee named Hanna is calling. Midway through our conversation, she says, Ms. Elham, do you know that today is an even more difficult day than the day we fled our homes? Can you imagine how it feels when you used to give to the poor to break their fasting, and now that you are a homeless refugee, must now rely on charity to break your own fasting? Her choked voice overwhelms the call to prayer.

Our conversation ends before I can mention that my fourth journal is full.

I will buy a new one and on the first page I will write the following:

My shore is no longer a harbour of love.

Seagulls soar chaotically.

Unable to land,

They search the seas,

The coasts,

For a ship,

A sailor

Who sails far away . . .

Elham Al-Zubaidi (Author) / AmirAl-Azraki and Sharon Findlay (Translators)

Elham is an Iraqi artist currently living in Basra. She is a poet, visual artist, women’s rights activist and director of Lotus Cultural Women’s League whose mission is to empower women and provide a platform for the female voice in Iraq. Elham is a well-respected and published author of poetry. “Camp Seagulls” is her first work of auto-fiction. It is based on actual anecdotal encounters with women refugees displaced by war and violence.

Amir is an Iraqi-Canadian playwright, literary translator and an Assistant Professor of Arabic language, literature, and culture at Renison University College, University of Waterloo. His projects in Applied Theatre have been employed in workshops throughout Canada, USA, Argentina, and Iraq. He has worked with women artists, students, and refugees, utilizing Theatre of the Oppressed techniques to address human rights issues. Among his plays are: Waiting for Gilgamesh: Scenes from Iraq, Stuck, The Mug, and The Widow. Al-Azraki is the author of The Discourse of War in Contemporary Theatre (in Arabic), “A Rehearsal for Revolution”: An Approach to Theatre of the Oppressed (in Arabic), co-editor and co-translator of Contemporary Plays from Iraq, and co-editor and co-translator of several published poems by Arab female poets.

Sharon is a Canadian writer, editor and scholar with a special interest in cultural memory, oral history migration and concepts of home. Based in Canada, her current research is focused on North African and Middle Eastern immigration to Italy.

Asmaa Samir is an Iraqi visual artist, professor and the chair of the Visual Arts Department at the University of Basra, Iraq. Her work is mostly concerned with the social and political oppression of women in Iraq.