As a Marine, I grew to appreciate contour lines—those brown lines and spaces on a topographical map–at The Basic School, in Quantico where I struggled to find marked ammo-cans attached to stakes jutting out of the earth, and hidden in vegetation or plain sight. All Marines learn orienteering at initial training and how to use the terrain to our advantage, but we also learn to view the battlefield from our enemy’s perspective–turn the map around–to find vulnerabilities and use it to influence plans, fortify positions, or lull forces into an ambush.

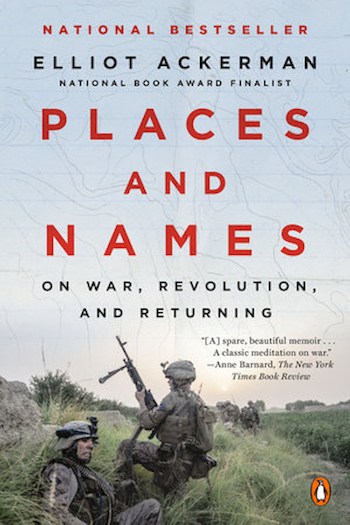

I suspect Elliot Ackerman turned the map when he wrote Places and Names. The book is laid out in a series of essays, not necessarily in chronological order, tying past to present where they collide in Fallujah–the summit. I came to this conclusion well into the chapter titled “Paradox,” where Ackerman admits “the story of Gunnery Sergeant Ryan Shane, a Marine from my infantry battalion, has always remained close.” He recounts the paradox of Fallujah while in attendance for Ryan’s award ceremony, where Ryan admits “I’m finding it really hard to accept that my greatest achievement as a Marine, this medal, also comes from my greatest failure.”

Ackerman reveals his greatest fear, while eating lunch in 2013 with Abu Hassar in Turkey: getting lost, which is both surprising and counterintuitive considering he served as an infantry platoon commander during the Second Battle of Fallujah or Operation Phantom Fury, the highest point of conflict during the Iraq War. I often think back to my deployment to Iraq and driving in a two-vehicle convoy there, and fearing a drift in longitude or latitude and getting lost in the barren landscape. This may seem trivial to the uninitiated, but Ackerman shapes the perspective with, “The great fears are chronic, never abating, threatening to wear you down. I’m still afraid of getting lost. You should see the map software on my phone.” The stress, sense of dread, the buildup of anxiety, of any time-length patrol or convoy is exhausting and compounded by the fact that so many other lives depend on you staying the course and arriving on time and on target. Not knowing where you are on the map affects fire support by air or artillery–possibly leading to fratricide–or casualty collection points for evacuation to the hospital via helicopter or plane (MEDEVAC).

Ackerman isn’t alone in his journey and throughout Places and Names he has several guides to help him navigate, like Abu Hassar who is introduced early on. Abu fought for al-Qaeda in Iraq, or AQI, where he smuggled guns and foreign fighters across the Syrian border into al-Anbar Province from 2005 to 2008, the same borders my fellow border transition teammates and I patrolled from January to September 2008. My transition team served as advisors to the Iraqi Border Defense Forces, with an area of operations that traced the Jordanian border to the Syrian border up until al-Qaim, a Port-Of-Entry town along the Euphrates. In a report to Congress at the end of 2008, Iraq Security Forces made significant gains in securing Iraqi population areas and the focus shifted to the borders and slowing the inflow of foreign fighters and weapons into Iraq. I don’t recall if my transition team and our Iraqi counterparts were tracking Abu. I wondered how things would have fared for Ackerman, if my team captured Abu.

Abed, a Syrian and former activist, arranges the meeting with Abu Hassar in a café in the town of Akҫakale, Turkey. Abed translates their conversations but then he excuses himself to go to the bathroom. Two veterans, on opposing sides are in fact left sitting side by side on a bench in Turkey. During this uncomfortable and awkward moment of silence between the two, Ackerman’s quick wit releases the pressure when he opens his notebook and sketches the Euphrates. Abu Hassar immediately recognizes this sketch and takes the pencil from Ackerman’s hand and draws the straight borderline between Iraq and Syria. Along the border Abu Hassar drew, Ackerman writes al-Qaim. They play this game, like Marines and veterans often do, of dates and places where each served–Haditha: 07.2004 / 02.2005, Hit: 10.2004 / 11.2006, and so on. I thought about the dates and places where I would fit in. I wondered about those intersections of space and time. I felt myself drifting, crossing wadis and porous borders like the Bedouins I encountered in the Syrian Desert. I suspect Ackerman intended the reader to add their own notes to the map and make the same connections with veterans of war on both sides.

In Places and Names, Ackerman makes his pilgrimage from Gaziantep, Turkey to Fallujah, Iraq. He’s unsure why he’s making it or what he will find. His carefully crafted essays jump from his wartime experience–Iraq and Afghanistan, to his recent days as a journalist. Ackerman ends the book with a combination of reflective memories and the Silver Star summary of action during Operation Phantom Fury.

Upon initial inspection, I questioned why an OIF veteran would want to return to Iraq–especially as a civilian and without a rifle, a platoon, artillery and air support. In one of the chapters, Ackerman writes about meeting expatriates while in the Middle East as commonplace. I grew to appreciate and develop a better understanding when I caught a glance at my wrist while my right hand supinated, holding the book–my wrist with a memorial bracelet similar to one Ackerman describes, the only differences are the place and name etched into the black metal. I recalled the different stages of grief and remembered everyone grieves differently and at their own pace. Most are familiar with five stages of grief–denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, but recently David Kessler, an expert on grief, presented a sixth stage: meaning. Ackerman’s travels was part of his grieving process. His descent from Fallujah concludes at home where he hid his old uniform after Operation Phantom Fury. He will take it out. He will look at it, press his fingers in the holes, trace out the blotchy stains, and wonder what to do with it. He will not be the same, he will still have the scars, but he will have the watch he wore at war to give to his son, and he will have his medals to give to his daughter. These gifts will serve as reminders of the paradoxes of life–our greatest achievements are tied to our greatest failures.

Francisco Martínezcuello

Francisco is a student at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. He was born in Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, and raised on Long Island. He deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan while serving on active duty in the United States Marine Corps. He has been published in Iron & Air Magazine, Wrath-Bearing Tree, Hippocampus Magazine and elsewhere.