Editor’s Note: At the end of this review are three poems from I Will Not Name It Except to Say that Consequence previously published.

Toward the end of I Will Not Name It Except to Say, there is a poem in which Lee Sharkey recapitulates and partially rewrites The Book of Job. As we know, Job is a good man, observant in his faith, yet he has been grievously and inexplicably harmed. His children have died, his crops and animals are blighted, and his body is afflicted with disease. He complains to his God that he does not deserve this suffering. He has honored God’s law, and the deity has a covenanted responsibility to protect him. As Lee Sharkey puts it, Job is not just complaining; he wants “a few words with the Unnamable.” He wants to know why all this suffering? Why is this happening to him? How could his God have let this happen?

The Almighty hears Job, and visits him as a voice inside the whirlwind. God explains, somewhat impatiently, that creating and sustaining the universe are tasks beyond human comprehension. Human suffering is a small matter in the cosmic scheme. Job is told he should consider the raw power of the beasts God has created. Job would thus realize that “Hope is a lie.” Upon hearing this, Job resigns himself to his fate: “I will be quiet, comforted that I am dust,” a line that serves as the title of this poem. However, Sharkey’s poem does not end there. Job may be chastened and reduced to silence, but the poet is not. She writes that this is the exact moment “where we would enter.” We are the creatures, she writes, “who may not have expected reward, but perhaps not so much suffering either.” Like Job, we cry out in our pain, but, adds Sharkey, we cannot “stifle the hope that rises each day in our throats.”

Poet, editor, educator, feminist, a peace and justice activist, Lee Sharkey passed away in October 2020. A longtime supporter of and contributor to Consequence, she was a poet with a dozen books and chapbooks to her credit. In every aspect of her life and work, she was not someone who would be silenced by whirlwinds, be they metaphysical or political, or some combination thereof. She was someone who on principle asserted and affirmed humane values in the face of whatever would deny or trample them. No doubt that Lee Sharkey too, at some point, wanted to have “a few words with the Unnamable.” This posthumous book offers us a core sample of what she might have said. Her words would not necessarily be reverent. They would be probing, wondering, skeptical yet earnest, and eager to talk. There would be questions and disagreements. What is the meaning of suffering? Is hope only a lie? What is this hope that will not be stifled? Is it more than wishful thinking? Questions of this sort are at the heart of I Will Not Name It Except to Say. They are raised within a framework of Sharkey’s secular humanism intertwined with her skeptical yet profound connection to Judaism. Although Sharkey’s poetry does not provide answers to these questions, to even ask them asserts their importance, and the dignity those who, in their pain, feel the need to ask them.

This book begins with a suite of poems wherein Sharkey responds to the dementia that has overtaken her husband. In her poem “Letter to Al,” Sharkey notes that she and her husband must now “live a routine of catastrophe,” each day holding no certainty other than the slow erosion of his cognitive abilities, and how that steals their future. At one point Sharkey says the dementia feels like an “imbecile cousin” of death itself. She refers to the illness as “the thing without a name” and thus implies that the disease is connected to the “Unnamable” in the Job story, is in effect another aspect of the whirlwind. And yet, despite the loss voiced in her “Letter to Al,” Sharkey’s poem brings us moments of crystalline tenderness. She tells of a night when the couple woke in a panic, each calling out the other’s names, each “fumbling” toward the other. Terrified by a dream, the poet’s husband pleads with his wife not to abandon him. She too no doubt feels the same way toward him.

Later in this opening section we find the poem that gives the whole collection its title. Instead of dignifying the illness with a name, the poet instead tallies up what the couple has made of their days together.

I Will Not Name It Except to Say

that this has happened, is happening

We read each other as lines slip down the page

More than the cardinal’s call

is how she flicks her tail

We have owned little, loved much

We made our hearts a heart with many rooms

Is this a version of the hope that cannot be stifled? If so, such hope is not what we ordinarily mean by that word. To say one might make out of suffering a more capacious heart reminds me of Vaclav Havel’s remarks about hope. Having spent years in prison for his political dissidence, the Czech playwright (and later the President of his country) observed that hope was not simple optimism. It was more than wishing that things would turn out well. Instead, Havel believed in a hope that grew out of the certainty that what one did made sense, that it was inherently valuable or good, regardless of the ultimate results. Similar to Havel’s thought, Sharkey’s poems suggest that our unstifled hope is related to meaning and meaningful acts in the face of suffering. Sharkey does not flinch from loss and pain, but unlike Job, she does not go silent. She is not made content by the fact that we all become dust in the end. For Sharkey, hope is the effort of making meaning, even in situations that are dire and hopeless.

After the opening poems about dementia, this collection expands outward in space and time, its aperture wide enough to include history, art, and politics. Approximately half of the rest of the collection is devoted to a variety of ekphrastic poems. These include a dozen prose poems in response to the paintings of Samuel Bak, a Holocaust survivor. Then comes a set of ten poems that reflect on the works of several artists in the German-speaking world during the years when the Nazis came to power. Later in the book is a lengthy meditation on the work of the feminist American painter, May Stevens, and in particular her paintings about the murder of Rosa Luxemburg. Each of these types of ekphrastic responds to artwork that arose out of historical chaos, and a culture’s descent into massive violence and moral morass.

Samuel Bak was eight years old when occupying Nazis forces imprisoned him and his Jewish family in the Vilnius ghetto. Bak and his mother eventually escaped and after the war emigrated to Israel. In 1993, Bak moved to the United States, settling in Massachusetts where he has lived ever since. Prolific, exhibited around the world, Bak offers us image after image of a haunted and shattered dreamscape: broken buildings, trees, crockery, stone heads, giant floating pears, just to name a few of his totemic items. His enigmatic paintings often hone in on one fundamental question. What kind of God could allow this world to collapse into genocide and the chaos of its aftermath? Bak’s In Need of a Tikkun is one such painting, and it prompted Sharkey to write this prose poem:

Tikkun

The scroll of the Law’s gone blank. An angel unrolls and holds it. A hole the size of a country appears in it, with tears branching out. Look, look! says the Angel of Melancholy, pointing to the rupture. It’s the inverse of the gesture for blessing that hovers over the tiny shack on the workbench before him, where smoke rises from the chimney. The woman who lives there has lit candles, covered her eyes, muttered the prayer over bread. She sits for a moment as stars rise in the heavens. Bending to lift a letter that fell from the scroll of the Law, she carries it to bed.

In the image itself (easily found online) one sees that these are shabby angels, with bedraggled wings and old tunics. They look panicked. The Angel of Melancholy holds a blank scroll, and all it can do is point at the damage done. The Law certainly is no doubt in need of repair, as the word tikkun suggests. Initially Sharkey’s poem describes the painting literally, but when she gets to the tiny shack, her imagination takes over. She adds to the painting a woman who lives inside the shack. The poet imagines that woman finding and saving a single letter of the alphabet that has fallen from the scroll. And she imagines that woman carrying the remnant letter into bed, possibly with her, or possibly tucking it in as she would a weary child. As with her version of Job, Sharkey partially rewrites the “text” of this painting. This woman does not completely restore the Law, but saving that letter certainly seems inherently worth doing.

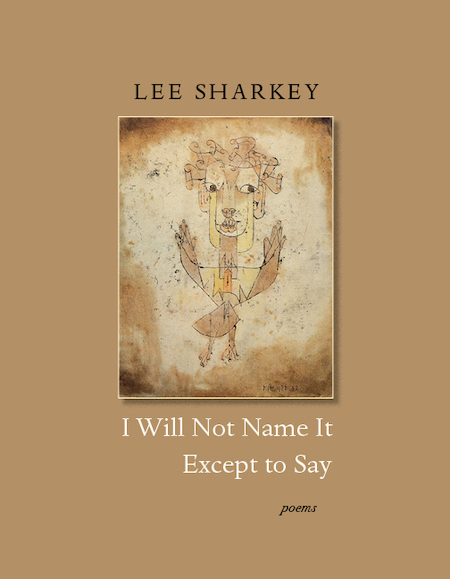

In the next section, Sharkey offers a suite of poems that deal with visual art that in one way or another bore witness to Germany’s political and moral descent into the Nazi era. These lyrics are rife with foreboding, with a poem based on Paul Klee’s 1920 monoprint, Angelus Novus, being a prime example. This is no guardian angel. With chicken wings and terrified eyes, it looks more or less helpless, and is being blown backwards by a storm in the world beyond the frame. Walter Benjamin, who owned this print, wrote in 1939 that this was an image of “the angel of history” frightened and carried backwards into the future by forces it does not understand. One art historian has even argued that Klee’s intent was to paint a satiric image of a young Adolf Hitler. For Lee Sharkey, the new angel is either a “dread messenger or dumbstruck witness,” and one can imagine it as both. The poem and painting both acknowledge how inadequate the “angel” is to the impending human catastrophe. It is also worth noting that this image of the new angel serves as the artwork for the cover of I Will Not Name It Except to Say.

The artists and their artwork in this section of the book bear witness to the unacceptable. Kathe Kollwitz’s 1923 woodcut, “Self-Portrait,” prompts Sharkey to write a poem in Kollwitz’s voice. Drawing upon what she calls “gleanings” from Kollwitz’s diaries, Sharkey’s poem presents a mother’s anguish. Kollwitz’s son was a soldier killed in World War I, and in both self-accusation and confession, Kollwitz in this poem says: “I am the woman who sent her son to war.” There is no way to change that fact. All she can do now, she says, is keep working, creating the images of her anguish, saying to herself, “I chisel in wood, a woman watching, / unmoving, no secret in her, just lines to rend, render me.”

In later parts of the book Sharkey brings in more fragments and “gleanings” from disparate other voices and texts. In “Thieves,” for example, Sharkey incorporates and responds to passages from Yitskhok Ruashiviski’s Diary of the Vilna Ghetto: June 1941-April 1943. In another poem she tells of a postwar letter from a cousin in Warsaw. In a note Sharkey says the long-ago letter “called on me to respond.” The texts that call on her to respond are not only the stories rooted in the Holocaust or earlier. For example, in one poem she writes of a newspaper account of librarians in Grozny who risked their lives to save books while under bombardment during the wars in Chechnya. In another she writes in response to the story of a Sumatran orangutan that had been shot seventy-four times with a pellet gun. The tortured animal was named “Hope” by the NGOs trying to save her. The poet is in dialogue with these narratives, and one can hear in these poems an echo of midrash, the scholarly Jewish practice of interpreting and commenting on sacred texts.

Responding to a passage from the Bible, or a work of visual art, or an excerpt from a diary or a letter lends a collage-like dimension to Sharkey’s poetry, the given “text” juxtaposed with her “reading” of them. There is also a meditative feel to these poems. Sharkey’s long lines move slowly across the page. Often they are end-stopped, sometimes without punctuation. Each line feels like a cluster of thought and feeling unto itself. Even the prose poems in response to the Bak paintings, with one poem per page, are surrounded with white space. From line to line and poem to poem I Will Not Name It Except to Say has a ceremonial pace. Grieving is the name of the ceremony enacted by Lee Sharkey’s poems, and grief is one of those places “where we enter” and try to sort out what our pain and loss might mean. Perhaps that labor is why Lee Sharkey’s poems don’t feel maudlin. Nor is there a hint of self-pity in this poetry.

In the final section of I Will Not Name It Except to Say, we return with Sharkey from her inquiry into public and historical grieving to the place where we began, to the poet’s private grief over the loss of her husband. In this last set of poems, there is solitude and pain, but there is also something else stirring within them. “Grief,” the final poem of the book, begins with Sharkey observing an emaciated woman going into a clinical setting for an infusion. The poet then thinks of her own husband, how she has tried to fathom and pry out what might be going on in his mind.

I study the woman’s bones and dark eye sockets and realize she’s a mirror

I study my love’s expression, looking to prise out what’s inside

A fingertip touches my throat

We are grass in a sandstorm

We may indeed be like grass in a sandstorm, but for Sharkey that it is not the whole human story. It is not even the whole story of this poet’s conception of or relation to the divine. At the end of “Grief,” Sharkey quotes from and responds to a passage in the Talmud, the collection of rabbinic teachings and commentary from the first to seventh centuries, C.E.

If a face arrives from the whirlwind calling itself indwelling

Not through gloom, nor through sloth, nor through levity or idle chatter

If the Shekhinah arrives and averts the sacrifice

If a wind with a face that speaks says build my dwelling here

Then I will remember joy

Then I will enter the sick man’s body

I am a citizen of this republic.

Some suffering makes us call out to whatever gods we believe in and ask why. Maybe, as with Job, the deity listens. Maybe the deity could do more than just put the questioner in her or his place. The “Shekhinah” in Judaism refers to the immanent presence of the divine, and it is thought of as a feminine dimension of deity. If the Shekhinah is just benevolent enough to avert sacrifice of any sort, then, Sharkey tells us, we will remember joy’s presence in our world and our lives. There is a huge if in these lines and elsewhere in this poem, but the ifs also express the hope of a skeptical believer, or a believing skeptic. We could call it a version of that unstifled hope Sharkey mentioned in the poem about Job. And if so, it is a hope that also undergirds our connections with our fellow human beings. We might empathically enter “the sick man’s body” precisely because that is what we are capable of, and sometimes actually do.

The declarative sentence that ends this book has an undeniable and nearly unbearable dignity to it. We are the creatures who know what loss is, and we are the ones who in our paintings, writings, and memories plumb the depths and meanings of suffering. We are the ones who shed the tears at the heart of things. Reading Lee Sharkey’s words here and throughout this collection, one cannot help but say in response, me too, “I am a citizen of this republic.”

![]()

SELECT POEMS FROM I WILL NOT NAME IT EXCEPT TO SAY

New Burnings Atop Old Burnings

A night march to a remote region of the country

An axe poised before striking the door of a house

The axe poised before striking

How many seconds to stare at a village in flames

To stay or to flee

To take off, or take the women and children

To run to the forest or cross to a neighboring village

To knock on a door and create a companion in fear

A gun to his back, will he plunder

Left to himself, will he steal the potatoes

Will he steal the potatoes but not the tractor

How many fields will he plow, over how many seasons

To walk past an old friend or meet at the bend of the river

To ask, where are the graves, or to answer

To count the old burnings and the new burnings

Our victims were second. Our victims were first.

~

Letter, Warszawa, 28 January, 1946

Three sheets of brown paper. Migrant. Survivor.

Ink burns what it doesn’t say.

How do I touch? Maker to maker.

Here’s where the nib touched down.

The letters have long downstrokes. They arch like serpents.

They curl like lambswool burning in the hills.

But where are the women, my dark-haired women?

My dark-haired man is composing a banquet.

My dark-haired man is composing a letter.

A package of food has arrived.

The table has known other legs. It wobbles.

Just one small bench to seat all the invited.

No cloth to spread but he’ll serve them according to custom.

Courtesies learned in the house of his mother.

And now he describes:

Those who fled east to the arms of the forest.

The blond one. The furtive who passed.

The passers who witnessed.

The city we leveled to save them.

My dark-haired women are sailing the sky in circles.

The table is groaning with food, real and imagined.

My dark-haired man is composing a toast.

Here’s to [my particulars] herring, whitefish, and lox.

Here’s to America, land of the innocent.

Here’s to my mother, namesake, sender of chocolate.

I traveled. I asked, Who eats from their china?

Who catches the wind with their linen?

I entered the shrines of those who betrayed them.

After seventy years he appears in a letter.

A box opens, brimming with food.

A bowl cracks on the counter.

I’m late. I’m late. I’m

Maker to maker, black bread and water.

I touch where his nib touched down.

A note on “Letter, Warszawa, 28 January, 1946” : Beginning early in 1938, my mother and her siblings tried unsuccessfully to bring their cousin Gisela and her three brothers from Poland to the U.S. The brothers joined the resistance and managed to survive the Nazi occupation; Gisela and her mother perished in the Lvov ghetto. A postwar letter from my cousin Ludwig, recently recovered from a small stash of WWII correspondence, called on me to respond.

~

Winter Tulips

Tracing a fear to its source leads us

to the Stasi, the floors of its headquarters

renumbered by the Minister of Security

so his office would be Room 101

suggesting that art is more powerful than the state

but not so simply, given the use states make of art.

When Reza Pahlavi banned these words

from poetry: winter forest tulip rose

the poet wrote

In___________ , in deep ___________ , I searched

for the _________ that would not bloom till spring.

Imagine, a grown man afraid of a flower!

~

Lee Sharkey was the author of Walking Backwards (Tupelo, 2016), Calendars of Fire (Tupelo, 2013), and five earlier books of poems, as well as a number of chapbooks. I Will Not Name It Except to Say, a collection of poems she completed in the last months of her life, will be published by Tupelo on May 1st. Lee Sharkey died peacefully in her home in Portland, Maine, on October 18, 2020.

Fred Marchant

Fred is the author of five books of poetry, the most recent of which is Said Not Said (Graywolf Press). He is also the editor of Another World Instead: The Early Poems of William Stafford (Graywolf), and with Nguyen Ba Chung has co-translated works by several contemporary Vietnamese poets. An emeritus professor of English, he is the Founding Director of the Poetry Center at Suffolk University in Boston.