In her paramedic training, Ieva Jusionyte was told, when dealing with gunshot victims, to “always look for the exit wound.” Exit wounds are larger and more irregular than entry wounds, and their location helps medical workers discover the pathway a bullet has taken through the body, so they can make a better guess as to the damage it may have done. Her book about the movement of guns from the United States to Mexico and their role in the violence related to drug economies takes Exit Wounds as its title. Just like literal exit wounds, the effects of US guns in Mexico are raggedy, unpredictable, and intensely destructive. Like an exit wound, a gun’s pathway across the border has legal, moral, social, and emotional dimensions. By studying how and where guns move, Jusionyte gives us a deeply humane diagnosis of the damage they do.

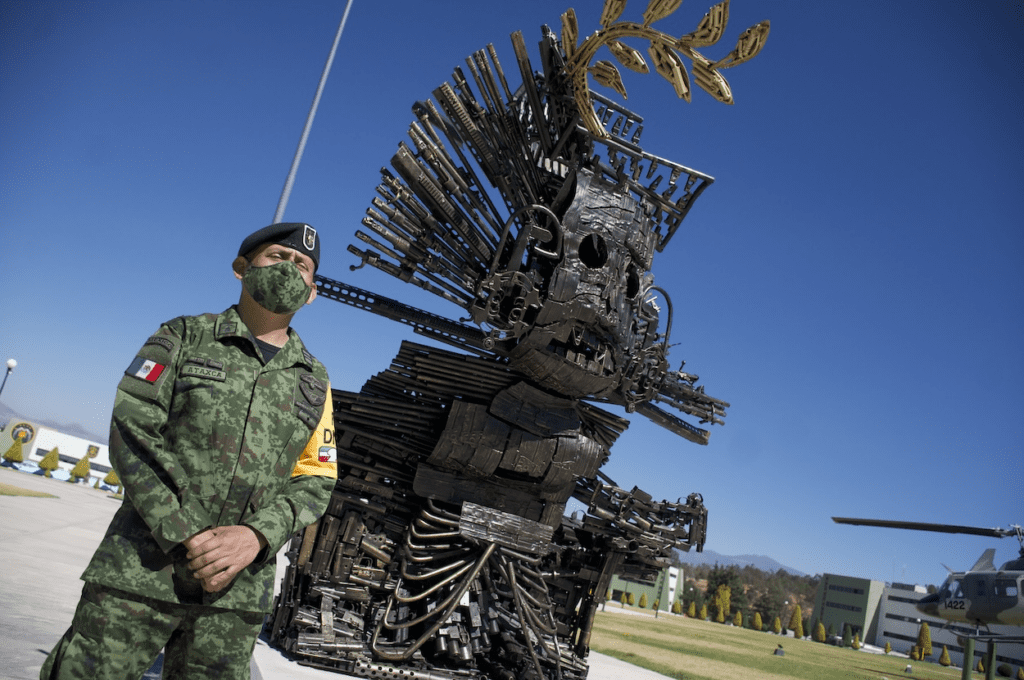

Dualidad | January 25, 2021 | Photo by Daniel Sánchez

Dualidad | January 25, 2021 | Photo by Daniel Sánchez

Exit Wounds (University of California Press, 2024) tells a story of complex entanglements. Trained as a cultural anthropologist and an EMT, with a background in journalism, Jusionyte saw the marks of Mexico’s surging violence on the bodies and lives of people while conducting field research in the cross-border Ambos Nogales region for her earlier book, Threshold: Emergency Responders on the U.S.-Mexican Border (University of California Press, 2018). Asking where the guns came from that inflicted these marks, she set herself on a journey across cities, the border, and into the varied lives and circumstances of people caught up in trafficking drugs and guns, as well as the people who study the traffic or attempt to enforce the law.

Mexicans, like their neighbors in El Norte, have a constitutional right to own guns privately. However, the individual right to bear arms is far less ideologically charged in Mexico, and gun regulation is nominally stronger. There are only two gun stores operating in Mexico, and 9,970 in the US states along the border. Seventy percent of the firearms found at crime scenes in Mexico originated in the United States, and at least two hundred thousand firearms are smuggled across the border (from north to south) each year (p.8). We are used to hearing about the entanglement of the two nations through the supply-and-demand dynamics of the narcotics economy, or through the movement of migrants across the “southern border.” Jusionyte reminds us that this line is also a “northern border” through which another commodity—not drugs but guns—moves, with dramatic physical and social consequences. Her strategy brings a new perspective on the militarization and violence that accompany a de facto “war” that the two countries are involved in—a conflict characterized in Mexico by illicit economies and overlapping ties between organized crime and governmental agencies. In the US, the conflict is motivated and shaped by demand for drugs, and by ideologies of masculinity, “freedom,” and patriotism. Armed conflict between military and paramilitary forces on the border and within Mexico continues to simmer, and the language of war pervades. Threats made by self-serving US politicians to attack Mexico, to build a wall and force Mexico to pay, and descriptions of immigration as an invasion only add a hazardous rhetorical layer. Exit Wounds helps us to understand the reality underlying the rhetoric, including the corruption and collusion in illicit local economies which involve human trafficking as well as drugs and weapons.

Jusionyte’s method was to follow the guns themselves, where they are made and sold, how they cross the border, who buys them, and how they are used. This approach took her to gun shops and gun shows, to shooting ranges, prisons, border checkpoints, bars, workplaces, and courtrooms, as well as people’s homes and cars.

While her method was to follow the guns, the book’s success lies in the people she meets and the stories they tell. Jusionyte reports these stories richly and with great sympathy, even for those, as she says, she “didn’t always agree with, but [had] come to care about nonetheless.” For instance, Miguel is a member of the Monterrey elite, a lover of hunting, the outdoors, and a gun aficionado. As a child he built an entire city from Lego, complete with a landing strip, illuminating it with Christmas lights. This detail helps shed light on his inventiveness and his individualistic, DIY approach to personal and familial protection. He tells Jusionyte that he responded to his city’s escalating violence in the 2010s not by barricading himself behind a wall guarded by private security forces and a cache of expensive weapons he didn’t know how to use (unlike many of his friends and neighbors) but by keeping a low profile, arming himself, but also taking a firearms course, educating himself about the arms he purchased and how to use them responsibly.

Juan, the person in the book with the closest affinity to Jusionyte herself, is a former history student and journalist who has, almost in spite of himself, dedicated himself to covering drug trafficking and organized crime. He participates in a state protection program for journalists, including a check-in every three hours when he is on especially dangerous assignments, as when Jusionyte takes him to a former massacre site in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila. Given the collusion between the police and organized crime, and how easily and quickly a person can be killed, Juan is understandably skeptical about how much protection the program really offers. When Jusionyte asks him how he copes with all the violence and death he encounters, he says, “Listening to Mozart, reading Shakespeare, looking at Rembrandt.”

Practically abandoned by her parents who moved to Texas and formed new families soon after her birth, thirteen-year-old Samara was living on her own in a poor neighborhood in Monterrey in 2009 when she was forcibly recruited (i.e., kidnapped) by the local branch of one of Mexico’s most powerful and brutal groups, Los Zetas. They terrorized her, but also trained her as a soldier. Samara is fiercely unwilling to see herself as a victim; she describes how she killed a famous and feared commander who tried to rape and brutalize her. For this she was tortured and nearly executed, but in a cinematic twist, eventually promoted within the group. Later, she was offered the chance to leave but turned it down, since Los Zetas were the only group she felt she belonged to.

By the time Jusionyte meets her in 2019, Samara has left Los Zetas, been raped and tortured by security forces, served her time in prison, received her high school diploma and a slew of other certificates, and is now attending university lectures and working at a lingerie shop in a mall. She is “on a new path,” although it’s clear her entire life and the lives of those she fought with, and those she has killed, have been irrevocably shaped by the violence of guns.

Jusionyte carefully weaves these people’s and others’ stories through her account, along with discussions of the history of iron production and gun importation in Mexico, the role of guns in US and Mexican national ideologies, the lawsuit by the Mexican government against US gun manufacturers, government policy towards and entanglement with organized crime, the ways drug trafficking and its violence has changed language (such as removing the word for the alphabet’s last letter, zeta, from general use in some regions), and more. While no one book can capture the subject’s totality, Exit Wounds provides a marvelous introduction, while also helping the reader see those caught up in the violence as fellow human beings.

What to include in a book on this topic is challenging; even more so is how to write about the topic without sensationalizing, justifying yet more violence, or portraying those caught up in it flattened ways. Jusionyte addresses this in an appendix on “methods, ethics, sources,” saying:

How do I talk about crime and violence without resorting to the language and categories that foreclose inquiry? . . . How do I write about Los Zetas—(the organization of the ‘last letter’)—without using words such as ‘cartel,’ ‘narco,’ or ‘sicario’? How do I find ways to represent people without assigning them to pre-established roles?

These are thorny questions. Even in writing this review, I’ve had to struggle with them, which made Jusionyte’s achievement in creating a readable and humane book even more vivid to me. She meets the challenge by choosing her vocabulary with care, crafting a narrative voice inspired not only by ethnography, journalism, but also the novels of Yuri Herrera, Roberto Bolaños, Toni Morrison, and others. Her chapters are short and she organizes them contrapuntally, a method of moving between the different protagonists and historical, legal, or political aspects of her stories. Often, she uses a striking image to evoke anxiety, grief, or courage in a condensed way—a handful of bullet casings, a torn kite, an exchange of WhatsApp messages, a line of cars under ashen clouds at the border.

Exit Wounds has, in a sense, two endings. In the penultimate chapter, “Metal’s Afterlives,” Jusionyte returns to the guns themselves, describing the patchy successes of gun buyback programs, and the recasting of decommissioned firearms as sculpture at military bases in the central plaza of Culiacán, Sinaloa, and elsewhere. The reader senses that Jusionyte would like to end on a hopeful note, although she isn’t quite able to, considering what she’s learned. She ends this chapter about efforts to build creativity and hope out of armament steel ambivalently, standing outside the historic Smith & Wesson armory in Springfield, MA, where guns are made first as “material for war” and, only later, and only sometimes, as material for art, memory, and peace.

The final chapter, “Epilogue” continues in a different register, striking a pragmatic rather than hopeful key by sketching a series of recommendations for laws and policies that might help unravel the threads of violence caused by drugs, guns, and war. These must, Jusionyte underscores yet again, be created from both sides of the border. She ends with another evocative perspective: an image from Nogales, Mexico, of two AR-15 rifles propped against the border wall, “both forged from steel. Both made in America.”

Elizabeth Ferry

Elizabeth Ferry is Professor of Anthropology at Brandeis University. Her research specialties include mining, finance, cooperatives, and labor in Mexico and Colombia. She is the author of Not Our Alone: Patrimony, Value, and Collectivity in Contemporary Mexico (Columbia, 2005), Minerals, Collecting, and Value across the U.S.-Mexican Border (Indiana, 2011), and with her brother, photographer Stephen Ferry, La Batea (Editorial Ícono, Bogotá/Red Hook Editions, 2017). With Stephen and the poet George Kalogeris, she co-edited of a book of poems by David Ferry, Some Things I Said (Grolier, 2023). She is currently writing a book about gold as a physical substance in mining and finance.