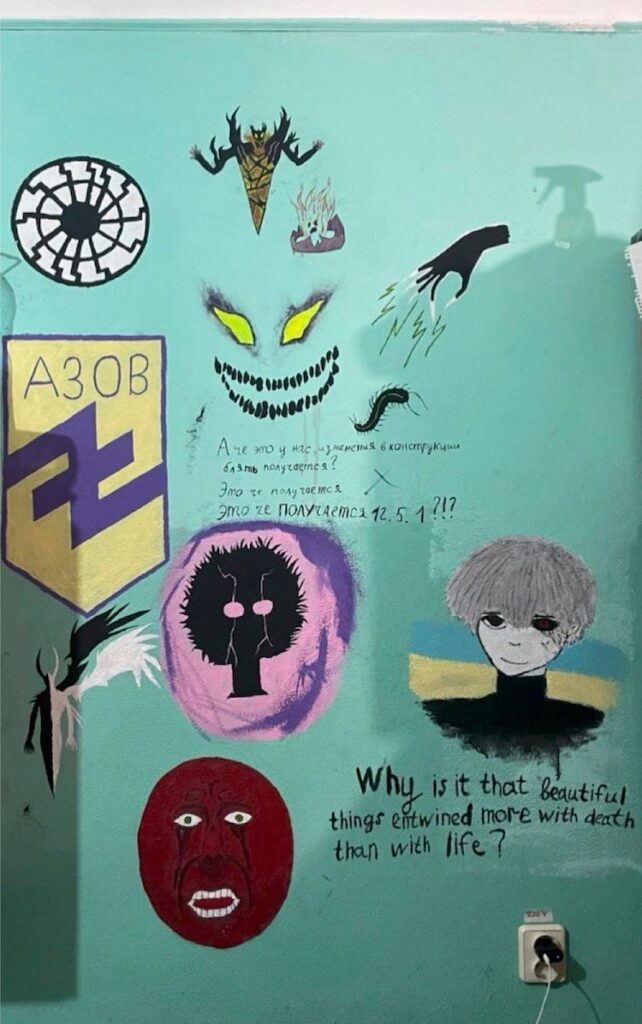

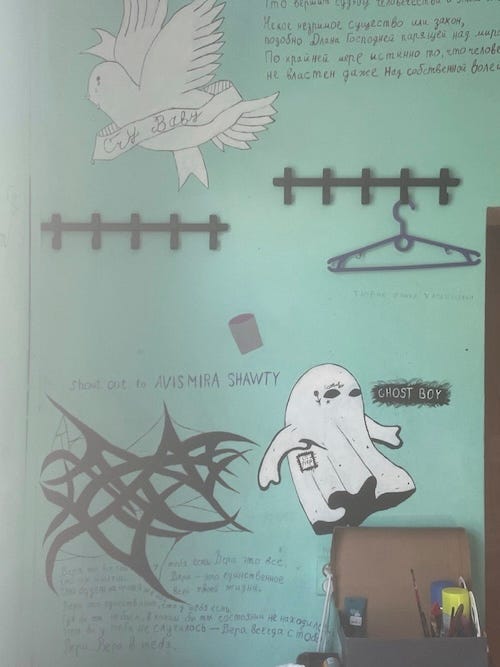

At first, nineteen-year-old Ilia Kashtalianov was not sure why he started painting the walls of his university dorm room in Kyiv. Once he began, he couldn’t stop. The multicolored images appeared as a hallucinatory mash-up of Chagall folk motifs and ghost-like creatures. It didn’t take long before other students heard about what he was doing. They soon came to see and discuss these beguiling murals growing around Ilia’s walls in the weeks and months after the Russian invasion of February 24, 2022.

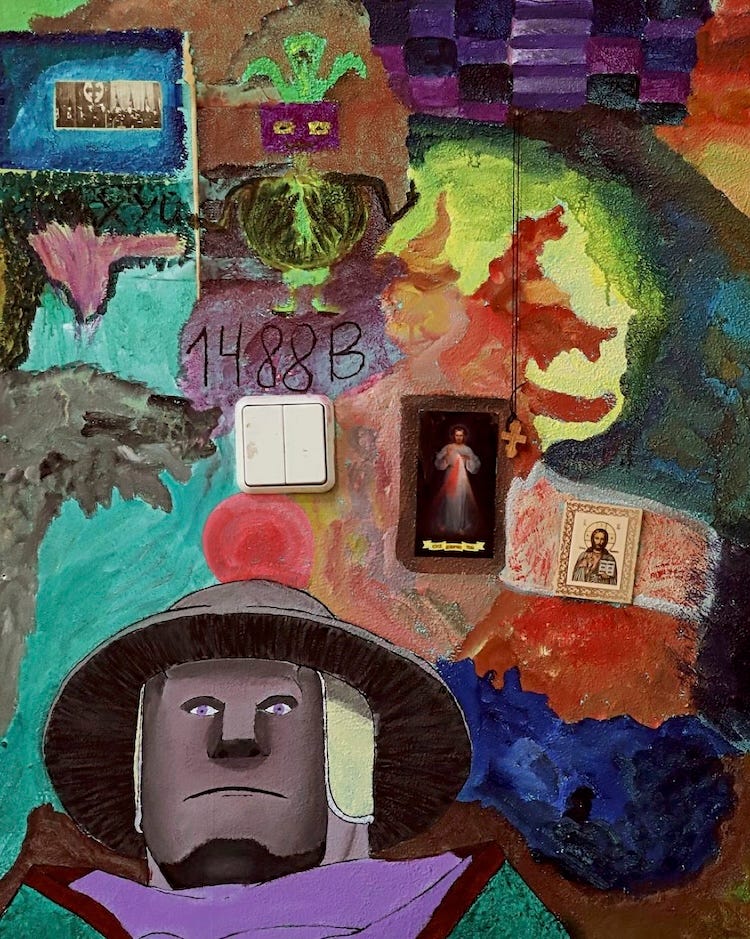

Image of painting courtesy of Illia Kashtalianov

Image of painting courtesy of Illia Kashtalianov

Today, Illia, who is studying geodesy and land management, tries to make sense of what he has done. “It is an inexplicable need to cry from your soul, to let the world know they should feel your emotions,” he said. “War is scary; it is a way to defend the country by my art.”

Illia’s desire to draw (see “Illia’s Response” at the end of the post) and have his art seen speaks to something remarkable unfolding in Ukraine today. Much of the world has at least some knowledge of the war crimes committed by the Putin regime against Ukraine’s civilian population. Less known is the cultural resistance to Putin’s attempts to rob the Ukrainian people of their national identity.

Since the Orange Revolution of 2004 and the Maidan Protests of 2014, and now in the grips of a devastating war, a real democratic sensibility has permeated through the culture that is different from its Soviet past. There is a spirit of an expansive and inclusive cultural identity about what it means to be Ukrainian in a humane and democratic society. It is not the angry and insular eruption of a MAGA type patriotism. It is something else that has emerged within Ukraine.

To better understand this phenomenon, we decided to interview artists and a new generation of Ukrainian university students who are forging a multifaceted cultural and democratic identity that defy Russian attempts to erase their voices. None of the people we spoke to or researched were naïve to the problems of corruption or bureaucratic inefficiencies that have plagued Ukraine since their Soviet past. At the same time, they told us how the arts have fostered new cultural spaces that value creative expression and critical discourse in their country.

Putin’s War on Ukrainian Culture

Ukraine does not exist in the mind of Putin, or indeed in the minds of many Russians, as an independent state. On the eve of the invasion, Putin underscored this point in a rambling speech to the Russian people, saying, “Ukraine is not just a neighboring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our history, culture, and spiritual space.”

Despite Putin’s absurd insistence that Ukrainian culture does not exist in its own right, the statistics of destruction tell another story. As of December 2023, the Ukrainian Conflict Observatory reported at least 1,690 Ukrainian cultural sites had been damaged or destroyed. This number includes 745 monuments, 532 churches and cemeteries, 132 libraries and archives, and 122 archeological and heritage sites. These are cultural war crimes as defined by the 1954 Hague Convention, which outlaws the purposeful destruction and looting of cultural property integral to a nation’s identity.

Something is Happening Here

Putin’s attempts to destroy all physical traces of a culture have backfired. Instead, the Russian invasion has accelerated a wave of cultural exuberance occurring at all levels of Ukrainian society. It’s not just the walls of Ilia’s dormitory that have been painted. Murals, posters, and photographs have appeared on bombed-out buildings and municipal halls across Ukraine. Nowhere is this more evident than in the frontline city of Zaporizhzhia. While the Western press has reported extensively on the Russian-occupied nuclear power plant eighty-three miles from the city, there is far less coverage of the emboldened artistic response to Russian aggression on the streets of Zaporizhzhia itself.

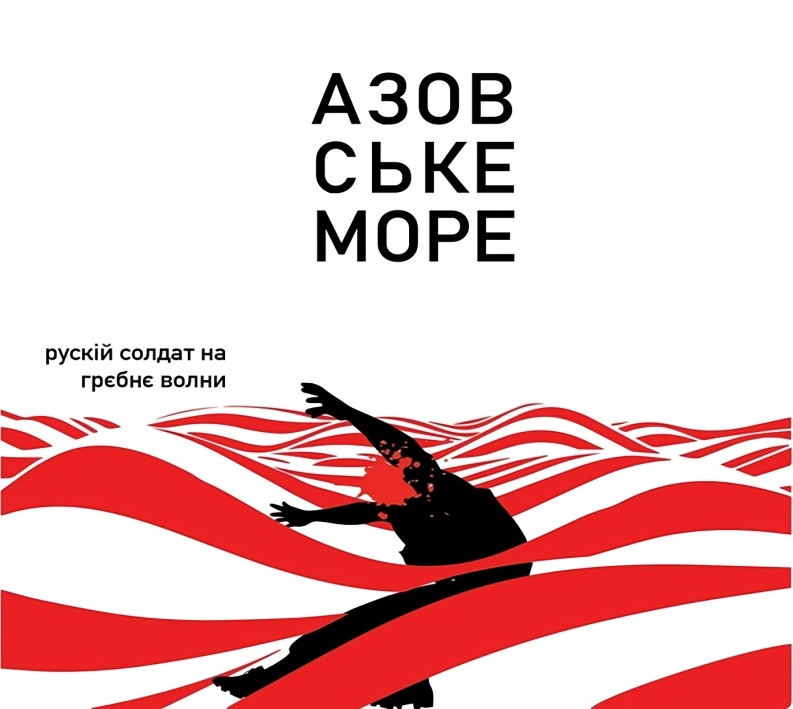

In October 2023, it would have been hard to miss the bright red and black colors of posters hanging on the windows of the Tourist Information Center.

Poster Image Courtesy of Natalia Lobach

Poster Image Courtesy of Natalia Lobach

They were part of an art exhibit by Natalia Lobach, an innovative urban planner and designer based in Zaporizhzhia. Natalia told us, “I make pictures that fight against Russian propaganda, I conduct city tours, I do art events for the LGBT+ community, and I give lectures about Ukrainian culture. I do this despite the fact that Russian shells are killing people in the city, destroying houses, despite the fact they are trying to leave us without electricity.”

At its essence, Nataliia’s art and the cultural events she organizes in Zaporizhzhia and in surrounding villages are about community. Compared to Soviet times, she sees that “the barriers between art, artists, and citizens seem to have fallen.” Her art has an intimate connection to the hopes and sufferings of Ukrainians under Russian attack both in the past and today. Zaporizhzhia based journalist, Marharyta Halich, explained, “Her pictures illustrate the desire and attitude of Ukrainians toward the occupiers. These pictures inspire and support our people. They are symbols of our struggles.”

Nataliia and many Ukrainians are rediscovering their connections (see “Nataliia’s Response” at the end of the post) to earlier Ukrainian artists and writers. She mentions the Ukrainian naïve artists, Maria Prymachenko and Polina Raiko, as inspirations. “I used their works in my posters,” she says. Prymachenko and Raiko began painting during Stalin’s reign of terror in the 1930s. While they’re labeled as “naïve folk” artists, there are often dark undercurrents of defiance in some of their early art. Many of Prymachenko’s works housed in the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum were recently destroyed by Russian shelling. Much of Raiko’s art was lost to flooding after the Russians blew up the Kakhovka Dam on the Dnipro River.

Whatever art that was lost by these legendary painters has not stopped Ukrainian artists from adapting cultural motifs from the past to address the hopes and fears of Ukrainians today. The Kyiv painter, Vitaly Kirichenko, draws images using colors and figures that have a magical feel to them. He also counts Prymachenko as one of the artists who has influenced his own style. He told us, “I draw something kind and bright about peace, and then it will bring peace to our lives.” While different in his approach and subject matter than Nataliia’s poster art, both artists want to use their art to help people cope with the burden of war and imagine a better future.

Another Zaporizhzhia artist has also adapted traditional designs in new ways. The photo artist, Tetiana Averina (see “Tetiana’s Response” at the end of the post), creates installations made from small metal darts taken from Russian cluster munitions. These metal fragments form a map of Ukraine laid on top of blood red woolen fabric. “I want to remind the world about this terrible war again!” Tetiana states on her Facebook page. “I urge my fellow creative people, Ukraine’s talent, to talk about it in their works! This is a creative front, and we must strengthen it!”

Image Courtesy of Tetiana Averina

Image Courtesy of Tetiana Averina

Crossing Genres, Crossing Generations

In another university dorm room, this time in Katowice, Poland, Aleksandra Ivanova takes off her headphones and puts down her book. Aleksandra, a student from Khmelnitsky, Ukraine, is far from the fighting in the Donbas. Yet, the Russian occupation of her homeland is always on the mind of this nineteen-year-old bio-technology student.

It’s a familiar routine for Aleksandra, listening to contemporary Ukrainian rock music and reading literature from a new generation of Ukrainian writers. This evening, she hears Serhiy Zhadan and Khrystyna Soloviy singing the hit song, “Heart.” Aleksandra loves the lyrics, which come from a poem written by Zhadan.

My dear, forests cry for us

I’ll braid their voices in hair

And all of those, who came for us,

on this apocalypse, on this fire show

Let them continue to hunt us

But the sky is formed by long terraces

And the light among the darkness

Zhadan is a well-known Ukrainian poet and novelist who also formed his own rock band. Soloviy is a rising star of Ukrainian pop/soul music. While the lyrics of “Heart” do not explicitly mention the war, Aleksandra told us that the song “helps me express my feelings in music and culture and helps destroy the obnoxious effect of the old Soviet Union on our life. Russian culture communicated an inferiority complex about being Ukrainian.”

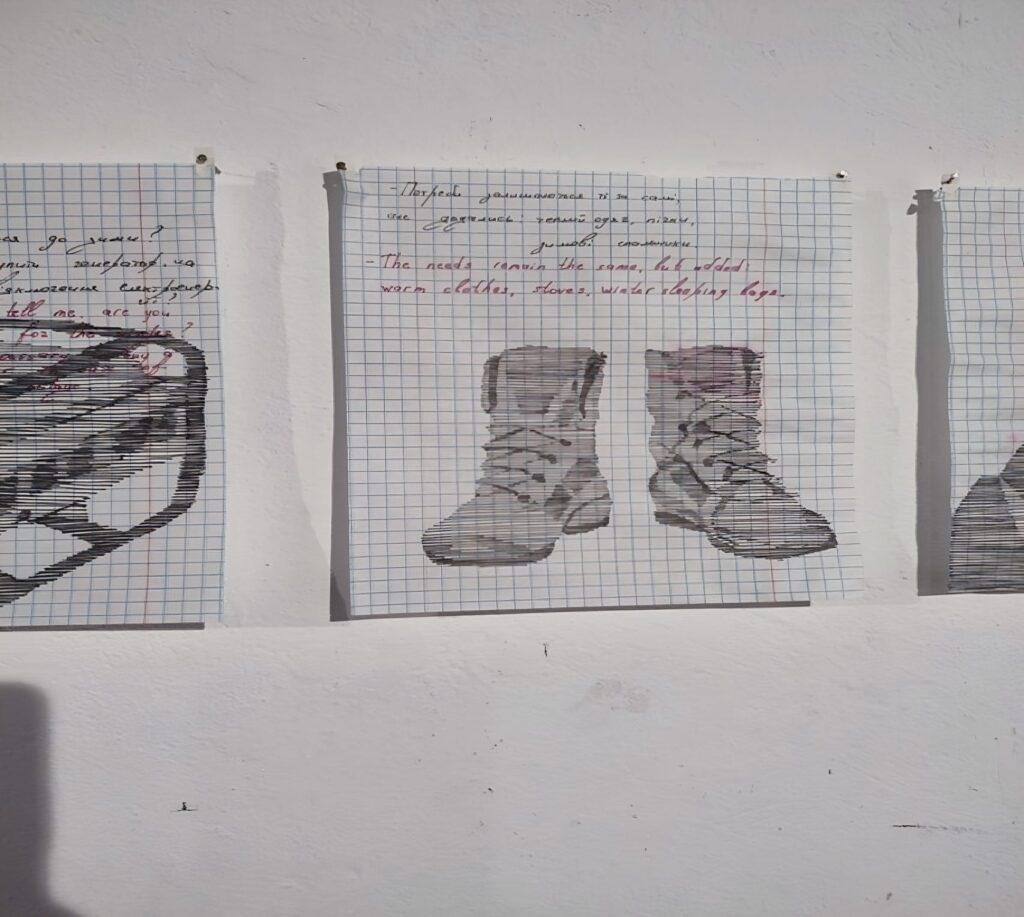

Besides embracing well-known Ukrainian musicians and writers, there is also a proliferation of spontaneous cultural performances by friends and strangers in Ukrainian neighborhoods. On a recent trip home, Aleksandra told us about seeing an exhibit of pencil drawings nailed up on a building in Lviv.

Photograph Courtesy of Aleksandra Ivanova

Photograph Courtesy of Aleksandra Ivanova

“We are continuously under attack by the Russians,” she said. “Not all of our art is happy, but it tells the truth for us. It is a way of thinking that we can survive and change things.”

The way the art is expressed matters less to many younger Ukrainians as long as it speaks to an emotional reality of their lived experiences. This sentiment is not just held by Ukrainian youth, though. Ukrainians across several generations are sharing a thirst for both older and newer forms of cultural expressions. In Kharkiv, Russian missiles have destroyed museums and concert halls, but people still find ways to gather to hear music. Old and young congregate in subway stations to hear classical and traditional folk tunes by local musicians.

People sheltering in a Kharkiv subway station listen to the concert on March 26, 2023.

People sheltering in a Kharkiv subway station listen to the concert on March 26, 2023.

(Thomas Peter/Reuters)

On the streets of Kharkiv, amidst the rubble of bombed-out buildings, Ukrainian cellist, Denys Karachevtsev, played haunting melodies for residents of the city in between missile attacks. To a reporter for The Washington Post, he said, “It raises people’s spirits. It makes people like me feel more eager to stand their ground and to not give up. To keep fighting.”

Denys Karachevtsev playing Bach’s Cello Suite No. 5 outside the remains of the Kharkiv regional police headquarters.

Denys Karachevtsev playing Bach’s Cello Suite No. 5 outside the remains of the Kharkiv regional police headquarters.

(Video image: Oleksandr Osipov via Storyful)

In the city’s bomb shelters and hospitals, Vera Lytovchenko plays her violin for Kharkiv’s residents whenever she can. As she told another reporter, her music reminds both Ukrainians and the world that “we are determined to fight for our lives and our culture. It helps us to still remain human.”

More than six hundred miles to the west of Kharkiv, the 2023 Lviv Book Forum brought together hundreds of people of all ages. Live events featured authors discussing their latest writing, along with classical and contemporary music in the evening. Kyiv university student, Olesia Vilshanetska, attended this festival and others like it. She told us that these events make her feel “connected to my culture, to my roots.”

It is at these festivals where a new generation of Ukrainians are exposed to a diverse range of writers they are now encountering for the first time. As Uilleam Blacker, a scholar at University College London and a judge at the 2023 Booker International Booker Prize, notes, “Young Ukrainians today are increasingly turning to great Jewish writers of the past to understand Ukrainian cultural history today.” Jewish, dissident, and Ukrainian nationalist writers from varied backgrounds who were banned in Soviet-era Ukraine are now having their works republished and discussed in bookstores, cafes, and festivals across Ukraine.

In interview after interview, and in numerous international reports on the state of Ukrainian culture, there is a repeated refrain that the arts are revitalizing a sense of cultural identity in the face of Russian aggression. Dimitri Vasylev, a fifty-two-year-old musician, put it this way: “I consider songs being on the frontline of the Ukrainian cultural war. I strongly believe this cultural war is no less important than the actual military opposition to Russia. I consider myself a soldier of the Ukrainian cultural army.”

Reaping a Bitter Harvest

The “cultural army” that Vasylev referred to has its roots in Ukrainian artistic movements during Imperial Tsarist and Soviet rule. Yet, each time in the past when there has been a hint of cultural, political, and/or economic autonomy by Ukrainians, Russian repression has followed. Of all the brutal Russian attempts to stamp out Ukrainian independence, Stalin’s actions in the 1920s and 1930s figure prominently into today’s cultural and military resistance to the ongoing Russian invasion.

Before Lenin died in 1924, he initiated a policy of indigenization in the Soviet controlled republics. This provided a temporary opening for Ukrainian cultural expression. After Stalin came to power, he believed this relative liberalization was a serious threat to his consolidation of centralized power. By the late 1920s, he had begun a campaign to eliminate all members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia.

In 1930, 259 Ukrainian writers were allowed to publish their work. By 1938, only thirty-six writers were published, and those who survived did so under severe censorship. Possibly up to thirty thousand writers, painters, and other cultural figures died by suicide or were executed, exiled, or “disappeared.” Among them were some of the most renowned Ukrainian artists of that era: Vasyl Ellan-Blakytnyy (poet), Valerian Pidmonhylnyy (novelist), Liudmyla Starytska-Cherniakhivska (literary critic/dramatist), Les Kurbas (actor), and Mykola Kulish (film director). In 1959, the Parisian magazine Kultura labeled the decimation of this generation of cultural creators “The Executed Renaissance.”

The loss of this generation is embedded in an even larger catastrophe that haunts the Ukrainian national psyche today: the Holodomor. The word is actually a compound of the Ukrainian holod (hunger) and mor (plague). According to scholar Anne Applebaum, the term first appeared in a few Ukrainian émigré publications in the 1930s. Today, in Ukraine, it refers to a series of three Soviet calamities perpetrated on Ukraine: the 1921–1923 famines; the 1932–1933 famines, arrests, and deportations of Ukrainian peasants and intellectuals; and the recurring famines of 1946–1947. They are commemorated each year on the fourth Saturday of November.

The 1932–1933 catastrophic years have been the most discussed and documented by international scholars and are now recognized as a genocide by most scholars. Raphael Lemkin, the legal expert who first coined the term genocide, labeled the Holodomor years of the 1930s as “a classic example of Soviet genocide.” Estimates vary on the number of Ukrainians killed by state-sanctioned famine and starvation, but most historians believe the number to be around four million people. How did this happen and why was this catastrophe barely known at the time?

In the early 1930s, Stalin’s disastrous policy of collectivization began the process of mass death in Ukraine. Essentially, produce harvested in Ukraine would no longer belong to Ukrainian farmers. Ukrainians were forced to surrender their grain, livestock, and equipment to government collectives. When farmers resisted, the Soviet secret police and army brutally suppressed any form of resistance.

As the famine worsened, Soviet authorities expropriated all produce that had been secretly grown or stockpiled by peasants, forcing many to leave their villages in search for food. Soviet authorities then prevented peasants from traveling outside of their villages. To survive, people ate grass, acorns, pets, and worse. They died by the hundreds of thousands at the sides of roads and on the desiccated fields that were once their farms. Those who managed to survive were often deported to other regions of Russia as slave laborers or simply executed for stealing or withholding buried scraps of food.

During these killing years, the Ukrainian borders were sealed off and the international press were not permitted to travel into Ukraine. Whatever information that got out was filtered through Russian propaganda promoting the fantasy that the deaths were the result of an unpreventable drought rather than the reality of Stalin’s policy of weaponized starvation. The few Western reporters who secretly traveled to Ukraine exposed some of what was occurring. This information, though, was either ignored or received skeptically by much of the mainstream press.

As the years passed, Soviet authorities consistently denied the policies of weaponized starvation that occurred during the Holodomor. Even the word famine was banned in public discourse until the collapse of the Soviet Union and the full independence of Ukraine in 1991.

The echoes of the Executed Renaissance and the Holodomor take on a powerful resonance in today’s Ukraine. Once again, this time under Putin’s leadership, the Kremlin is attempting to deprive Ukrainians of basic food sources. The Hague-based NGO, Global Rights Compliance Foundation, has accused the Russians of war crimes involving systematic “starvation and pillage” of Ukrainian grain. Up to twelve thousand tons of grain per day have been stolen from Russian-occupied land in Ukraine via railway and cargo ships to Black Sea ports.

The deprivation caused by the destruction of Ukrainian food sources has intersected with the traumatic legacy of the Holodomor for Ukrainians. It is no wonder that the metaphors of grain and bread have figured into Ukrainian art. The trauma of the past and the crimes of today have been transmuted into artistic exhibitions that honor what has been lost but also have pronounced a stance of resilience and defiance in the face of oppression.

The recent exhibition Bread of War by photographer Igor Gaidai is one such example. His 2023 exhibit at Art Gallery Ukraine consisted of large photographs of loaves of charred bread. At the opening of the exhibit, Gaidai stated the following to a Ukrainian journalist from Vikna News: “I transformed my feelings into works, showing giant breads burned to blackness. This is just my reaction to today’s events, to what Russians want to do to our people, not just killing, but trying to destroy our values, our identity via destroying our bread.”

Photo courtesy of Igor Gaidai

Photo courtesy of Igor Gaidai

The exhibit touched a nerve for visitors and the thousands who have viewed the photographs online. One woman who attended the opening stated that there was “deep philosophical meaning in the concept that this bread is not burned but just slightly charred. This means that the core of this bread remains intact, and the same I can say about the core of the Ukrainian people.”

Gaidai told us that this exhibit, and most of his work over the past several years, formed part of a larger cultural statement. “Much more important is how culture preserves our identity,” he said. “It is in a way a symbol that allows us to be united. Culture is power.” Proceeds from the gallery exhibit have been donated to the treatment of children and Ukrainian soldiers wounded during the war.

Gaidai is not alone in wanting his art to contribute to both the physical and cultural survival of Ukraine. Many Ukrainian artists are finding creative ways to contribute to the resistance and at the same time draw greater attention to the daily sacrifices Ukrainians endure during the war.

Zhanna Kadyrova has taken this imperative to new levels. In her 2022 exhibit Palianystsia, Kadyrova wrote that after the Russian invasion “art was absolutely powerless and ephemeral in comparison to the merciless military machine destroying peaceful cities and human lives. Now I no longer think so: I see that every artistic gesture makes us visible and makes our voices heard!” The creation, exhibition, and reception of Palianystia was her gesture to make Ukraine heard and visible in the world.

The word Palianytsia is the name of a Ukrainian round wheat bread that has been part of Ukrainian culture for centuries. When the war broke out, Palianytsia also became code for Ukrainians to distinguish friends from foes. Kadyrova liked the name of the bread because, as she says, “Russians can’t pronounce Palianytsia correctly.” Whether that is true or not, it reveals the sly wordsmithing of the artist. It also is symbolic of the nutritional and spiritual sustenance bread provides in the lives of Ukrainians, something Russian authorities have once again tried to steal or destroy.

Using stones from a riverbed gives the viewer an impression of timelessness and solidity. Yet, there is also a lightness and freshness to the loaves, as if they were just baked. This alchemy of creation has allusions to the resilience of the Ukrainian people in the face of Russian attacks on their food source and very identity as a nation.

Zhanna Kadyrova – PALIANYTSIA (PARIS) 2022, Photo: Oak Taylor-Smith

Zhanna Kadyrova – PALIANYTSIA (PARIS) 2022, Photo: Oak Taylor-Smith

Good Evening, We are from Ukraine

A simple phrase became a greeting, then part of a song track, and then a meme that proliferated through Ukrainian culture after the Russian invasion. The words “Good Evening, We are from Ukraine” have been integrated into music videos that have gained more than seven million views on YouTube. More than six hundred million TikTok clips feature the phrase. It’s also made its way onto a popular postal stamp featuring a tractor, with a Ukrainian flag on top of it, pulling a disabled Russian tank behind it. Music videos by Ukrainian soldiers frequently employ the phrase in rousing patriotic anthems of the “good fight.”

For many in the international community, it might seem strange that such a simple phrase has achieved the degree of media exposure and popularity it has. Yet, when one recognizes that Putin and the Kremlin spin doctors have promoted the canard that Ukraine is a fiction, that it has no independent national or cultural identity, then the phrase makes perfect sense as an assertion that we more than exist, we have a history and a future. When the phrase is uttered and sung over and over again, it becomes a linguistic weapon that punctures a hole in Putin’s Orwellian universe.

Today and Tomorrow

More than two years have passed since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. We decided to check in with some of the people we interviewed back in the fall of 2023 to find out what, if anything, has changed in their thinking.

The passion that drove Illia Kashtalianov to paint the walls of his dormitory room still burns brightly, but it’s also layered with other emotions. He wrote us saying, “Perhaps I have already stopped feeling something towards the enemy, only conscious anger remains. For my compatriots, those who are now at the front or those who were forced to flee the war, I feel only sorrow . . . Their pain continues to become mine and the further it goes, the more this cup fills up.” He added that he still wishes “for a speedy victory for my country” and “the triumph of justice.”

For the Zaporizhian artist and activist, Nataliia Lobach, her reflections take on a different tone. “Now is a difficult period,” she says. “At first there was a feeling that the war should end soon. There was a feeling that a democratic world would not tolerate the violation of all human rights. Now the feeling is that this is a reality, and that we constantly have to prove our ability to fight for our own existence.”

Marharyta Halich, having interviewed countless wounded soldiers and traumatized families said, “Every day, Ukrainians, including me, feel indescribable pain, despair, and rage.” She emphasized, though, that “Ukrainians continue to live and try to find beauty every day. This is proven by our cultural figures who create new works of art that help the morale of our soldiers and citizens.”

The voices of the artists and students in this article hardly constitute a representative sample of Ukrainians. What they do, though, is open a window, however small, into the cultural traditions and innovations—past and present—that keep the spirit of a beleaguered nation at war rooted in a humane hope for a decent and dignified life. It is a life force that is struggling to survive in the shadow of a malignant monster mining its harbors, flooding its land, and bombing its homes, schools, and hospitals.

Will we who live in countries that profess a semblance of democratic values allow the voices of resistance in Ukraine to go silent? Will we be the ones who turn away and allow the night to descend upon Ukraine only to realize after it is too late that the night has come for us?

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate the time and trust given to us by the Ukrainian artists and university students we interviewed. A special thanks to ENGin, an educational NGO based in Ukraine, for putting us in contact with Ukrainian English learners who were interested in sharing their thoughts and feelings about how Ukrainian culture is evolving in the face of the Russian invasion.

Illia’s Response

My story as an artist began in April 2022, when the Russian troops fled the Kyiv region, and I was able to return to my dorm room. I came back with a clear intention to draw on the walls, to take a paintbrush in my hands and create for the first time in my conscious life. My first drawings were nothing special, I was just learning and filling my hand, depicting symbols that I liked.

The real art began absolutely spontaneously in the course of my creative journey, I developed a certain principle – always use all the colors with which you paint. That is, when after the main act of painting I had leftover paints, I decided to try to paint these remnants on the walls in any order.

Initially, I didn’t give any seriousness to what was painted on the walls, I just applied the leftover paints there. That’s how my first real creation came out:

When my first wall art was finished, it hit me: this is my style!

That’s how the concept of my wall painting matured: 1) Random colors, 2) Spontaneous mood, and 3) Lack of a clear idea.

I didn’t paint anything intentionally, I just let the brush in my hand move in proportion to the impulse of my soul. After the initial colorful canvas is created, my imagination begins to work, expressing my subconscious images. I did not consciously put any meanings into these paintings, but the meanings emerged beyond my will and also because of it. The series of wall works is the purest product of sublimation of objective reality through myself.

This series of works includes six paintings, they were painted almost in parallel during a year, but remained unfinished, not finished because I had to destroy them due to barbarism and rejection of the beautiful work by the administration of the campus and the university.

Since the works took more than a year to create and were painted from day to day, they capture the full range of emotions available to a person from melancholic sadness to manic joy, from idle celebration to complete despair.

In its essence this creativity is absurd, I always knew that sooner or later I will leave my room, but persisted in creating, like Sisyphus rolling the stone on the mountain, but unlike him, I had hope that these creations will remain in this room for future generations of students, igniting the flame of creativity in their hearts.

All works are made with acrylic paints and various brushes.

Nataliia’s Response

Maria Prymachenko and Polina Rayko are artists with different backgrounds and different skills. But both of their work speaks to our cultural identity. Irrepressible fantasy, fantastic animals, bright rich colors. This is what I look at and understand—this is us, this is me.

Tetiana’s Response

We are tired of pain; instead, I would like to bring more beauty to the world! I spend most of my time taking photos, and I’d like to share a miraculous experience I had thanks to photography.

In the spring of 2014, I received an unexpected message on a social network from NASA employees. They wanted to print my “Interplanetary Spring” photograph and send it into space. Though I couldn’t quite believe it at first, I eagerly agreed. Our mutual appreciation for the photograph bridged the gap despite the language barrier.

On May 28, 2014, the spacecraft “Soyuz TMA-13M” launched, carrying “Interplanetary Spring” on board. They informed me the photograph might return with a subsequent crew, but the timeline was uncertain. I often gazed at the sky during this period, whispering, “A piece of me is flying up there.” The feeling of an invisible connection between me and my photograph never left me.

For almost six months, my photograph traveled through space. Astronaut Gregory Reid Wiseman even took a picture of my photo, attaching it to the porthole against the background of the Earth, and explained: “I tried to find the most interesting view of the Earth. This is over Africa before sunset, so the clouds give a beautiful shadow.”

When the photograph returned to Earth, the astronauts sent it back to me, now infused with cosmic energy, along with a “Certificate of Compliance with the ISS Expedition 40/41.” I had never received such a document, and it now proudly adorns my wall alongside my photo contest diplomas.

This experience is a testament to the miracles that can happen to anyone at any moment.

Thanks for this powerful piece–a testament to both deep grief brought on by terrible destruction and deep joy and the will to create and survive.