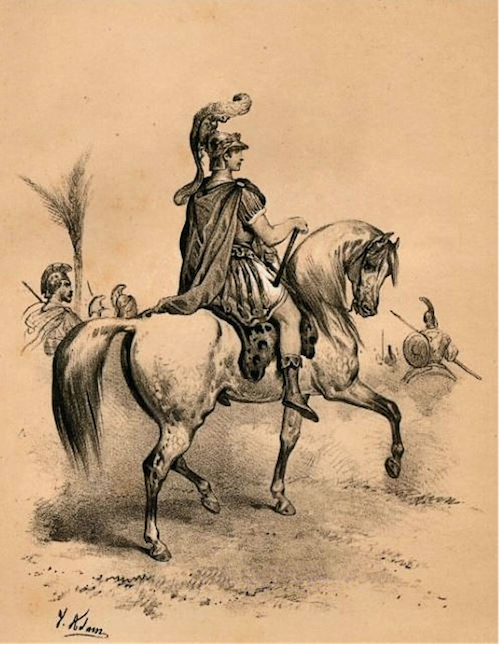

“Alexander and Bucephalus” by Victor Adam Lemercier

You’re a foot soldier in the invincible Macedonian army. You are led by a man named Alexander who may be a god. But lumbering toward you on this day in 331 B.C. is an animal that outweighs you by 6,000 pounds. It is armed with elaborately lethal spears aimed at just about the height of your head. Several soldiers of the opposing army ride in a gazebo atop the creature. Two of them are winging arrows in your general direction. The animal is what we now call an elephant. Its trumpeting roar is louder than you thought any noise could be. The ground trembles as several of the beasts advance. What do you do? Most likely you do what any sensible soldier would do in similar circumstances. You run.

*

The evolution of warfare during the last century has worked to the advantage of several animal species. Horses, elephants, oxen, and mules are no longer conscripted en masse to aid in our territorial and ideological struggles. Like the Gatling gun and the Jeep, they have been replaced by weapons and means of transport that are bigger, faster, and stronger. For centuries, however, military strength required four-legged support. Semirimis, a legendary queen of Assyria, was said to have been so unnerved by her own army’s lack of battle elephants that she had a herd of moveable fakes, Potemkin pachyderms, constructed for purposes of intimidation.

*

The Asian elephant has been employed for a variety of purposes in India since the Indus civilization, which flourished from approximately 2500 to 1500 B.C. Its military use probably evolved during many years of domestic service in clearing brush and hauling logs—work that segued nicely into the similar tasks involved in demolishing enemy breastworks. Eventually these pachyderms became mobile troop platforms, used to spearhead infantry assaults. Indian elephants so deployed were hung with bells. Their tusks were bound with hemp or metal for added strength, the tips of the tusks affixed with daggers sharp enough to fillet fish. The animals killed, says Herodotus, by “trampling some men under their feet, ripping up others, and tossing many into the air with their trunks.” It was a monstrous, dishonorable death.

*

Less imposing than the elephant, the horse has been of far greater tactical importance to the course of military history. Horses have mattered for as long as records have been kept. The Hyksos invasion of Upper Egypt in the 19th Century B.C., for example, was probably successful because of the invaders’ use of the horse-drawn chariot, until then unknown to the Egyptians. Such chariots may in turn have been adopted from the Babylonians, into whose lands horses were introduced from the north around 2100 B.C.

*

Alexander the Great’s first recorded triumph was his taming of the stallion called Bucephalus (literally, “Ox Head”). Given to Alexander’s father by one of his generals, the horse defied every man who tried to ride him. Onlookers laughed when young Alexander announced that he would mount the animal. Seizing the horse’s halter from another man, he pulled Bucephalus halfway around, then sprang into the saddle—”to the applause of courtiers and his father’s tears of joy,” writes one historian. Only the boy had noticed that Bucephalus was frightened of his own shadow. By turning the horse toward the sun, Alexander began a relationship that was to last some twenty years.

*

It was said that Alexander commonly rode another horse to the edge of battle, mounting Bucephalus just before he entered combat. When Bucephalus was finally killed, at the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 B.C., Alexander mourned for weeks. He had a city built over the animal’s grave.

*

Presumably Bucephalus and Alexander saw their first elephants together. This would have been at Gaugamela in 331 B.C., where the Greeks fought Darius I and his Persian army. The elephants obviously weren’t the deciding factor in the battle, because Alexander won. Still, he recognized the military significance of the creatures. Horses bolted and fled. Despite being armed with the 16-foot spears called sarissas, his foot soldiers were helpless against their charge, and often simply ran away. Alexander began scouting for his own elephants even as his armies ranged further east. He sent dozens of the animals back to Greece from India.

*

Though mounted troops were an important asset in Alexander’s day, he and his cavalry lacked what to modern eyes may seem like an obvious advantage: the stirrup, which wasn’t invented until sometime in the first century A.D. Because they lacked stirrups, Macedonian riders tended to fight much like men on foot, wielding their spears overhand rather than couched under one arm. Also, because the Macedonian war horse was small, standing only about fourteen hands, cavalry was less formidable than it would later become.

*

Dogs have always been the most enthusiastic animal conscripts in human wars. The mastiffs of the Celts fought fiercely alongside their masters against the Romans when Julius Caesar’s legions pushed northward in the first century B.C.—so fiercely, in fact, that Rome later set up a sort of recruiting station in Britain for acquisition of the animals. Centuries later, the Spanish used dogs in their wars against the indigenous peoples of Central and South America. The animals were so effective in their bloody work that the King of Spain recommended the animals be granted military pensions.

*

Elephants were never eager to fight. In fact, it was their unpredictability in the face of battle that spelled the end of pachyderms as combatants. At the battle of Metaurus, reports Livy, “more elephants were killed by their riders than by the enemy. The riders carried a mallet and a carpenter’s chisel. When one of the creatures began to run amok and attack its own people, the keeper would put the chisel between the elephant’s ears at the juncture between the head and the neck and drive it in with a heavy blow. It was the quickest way to kill an animal of such size once it was out of control.”

*

As elephants fell into disfavor, the horse became, for the next two thousand years, the single most important asset a man could have in attempting to kill other men.

*

The image of man and animal fighting a common enemy is archetypally attractive. St. George is mounted when he fights the dragon. The Valkyries of Norse mythology ride winged steeds as they usher brave souls to Valhalla. In the Book of Revelations, Christ returns to Earth on a white horse to “judge and make war.” Less compelling but still instructive: easily half of all fantasy fiction produced in the last century depicts humans or human surrogates battling evil with the help of animal allies. Frequently, the animals are dragons—see, for example, George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire. Other notable conscripts: “tarns” (pterodactyl-like creatures in John Norman’s wonderfully awful Tarnsman of Gor series), a sheepdog (Harlan Ellison’s “A Boy and His Dog”), giant eagles (The Hobbit), and an entire menagerie of woodland mammals (in C.S. Lewis’s Narnia saga). Man, separated from the natural world by his self-awareness, perennially tries to assuage the loss by imagining animals that will come to his aid in the face of some existential crisis—as if, through our own rapacity, we hadn’t forfeited the right to such assistance long ago.

*

Some historians credit the Huns with introducing the stirrup to Europe. If this is true, what may have been their single contribution to Western civilization was a significant one. As Robert L. O’Connell writes in Of Arms and Men, the stirrup dramatically increased the advantages of mounted men over those on foot. By rising in his stirrups, rather than sitting with his legs gripping his mount, the rider could deal savage blows with his sword. And rather than thrusting or throwing his spear overhand, the mounted lancer could now hold his weapon at rest in the crook of his arm, using the combined weight of his body and his charging stallion to deliver a blow so powerful that baffles were added to lances to prevent them from penetrating too far into the flesh of opponents and getting stuck.

*

Charles Martel, King of the Franks, began incorporating cavalry into his army in the 8th Century A.D. in response to Moslem incursions into Europe from Visigothic Spain. The Moslems were primarily mounted soldiers, what might be termed light cavalry. Though Charles turned back these invaders at the Battle of Poitiers, he was frustrated by his inability to pursue his more mobile opponents. If the Franks were to cope with the Muslims, at least some of the Franks would have to ride.

*

The medieval knight’s destrier, or war horse, was bred to be “strong, fiery, swift and faithful.” En route to battle, the warrior rode his palfrey, a horse that was also high-bred but of quieter disposition. Like Alexander the Great, one of the Nine Worthies emulated by European warriors of the Middle Ages, the knight switched mounts just before combat. For military purposes, writes Barbara Tuchman, “horse and rider were considered a unit; without a mount, the knight was a mere man. For a knight to ride in a carriage was a breach of the principles of chivalry and he never, under any circumstances, rode a mare.”

*

In adopting ever heavier armor, including head- and breastplates for their horses, European knights moved counter to the preference of Eastern armies for mobility. The Mongol invaders of the 13th Century provide a good example of this preference. Clothed only in furs and boiled buffalo hide, and armed with powerful composite bows they could fire accurately even over the rumps of their ponies, the Mongols were the deadliest force on earth, like a human plague that destroyed everything it encountered. Marco Polo reported that in the Great Khan’s army, each warrior was obliged to take with him on campaign eighteen horses and mares, so that he might change his mount as often as he needed. The ponies also provided sustenance: the Mongol ate a pasty form of dried mares’ milk on his journeys. For additional nutrition, it was said that he would pierce a vein of one of his horses and lap its steaming blood.

*

No matter whose flags flew at the front, there were always animals behind the lines. They hauled equipment and food, water, and weapons. Sometimes these pack animals were horses. More often they were oxen, camels, mules—occasionally yaks, even reindeer. Pack animals show up in the annals of warfare wherever men do. In 547 B.C., camels in the Persian army of Cyrus the Great badly frightened the cavalry of the Lydian king Croesus. 2500 years later, Ernest Hemingway writes of seeing mules slaughtered in the retreat of Greek forces from their Turkish enemies during the First World War: “The Greeks were nice chaps too. When they evacuated they had all their baggage animals they couldn’t take off with them so they just broke their forelegs and dumped them into the shallow water. All those mules with their forelegs broken pushed over into the shallow water. It was all a pleasant business. My word yes a most pleasant business.”

*

It is thought that the armed forces of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics employed some 1,200,000 horses during World War II.

*

According to the Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, the elephant’s importance in battle is illustrated in the game we now know as chess. The original pieces represented the constituents of an Indian army: the king, his vizier, war elephants, cavalry, war chariots, and foot soldiers. In the movement of the game from India through the Moslem countries to Europe, the alfil, or war elephant, was gradually transformed into the bishop. It is said that at some point, the two points on the top of the alfil meant to represent the elephant’s tusks were misinterpreted as the double points of a bishop’s mitre.

*

Weapons of war seem to be evolving along two very different paths. On one are increasingly precise, technologically aided armaments. These so-called “smart” weapons, beloved by the Pentagon, are supposed to be able to hit targets with such accuracy as to minimize damage to civilians and civilian property. On the other path are what might be called, “dumb” weapons—chemical and biological armaments. Once introduced into a human population, an organophosphoric substance like sarin is indiscriminate. It attacks whatever it touches.

*

The National War Dog Memorial is located in Hartsdale Canine Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. The memorial was built from the contributions of American schoolchildren after the First World War. The heroics of dogs in combat—from Sergeant Stubby in the First World War, through Chips in World War II, Nemo A534 in Vietnam, and Lee in Afghanistan—have been well documented. Motivated by protective, pack, and predatory instincts, dogs routinely perform acts we classify as gallant or heroic. These aren’t really the right categories, of course, as heroism implies an ability to choose a course of action rather than an instinctive reaction to some set of circumstances. While dogs’ senses are uniquely valuable on patrol, rescue, and mine-removal operations, canine loyalty to human handlers is the ultimate reason our military won’t stop relying on them any time soon. Dogs make us feel good about ourselves—even as we’re killing other people.

Elements of the U.S. Air Force recently completed exercises with the Ghost Robotics (“Robots That Feel the World”) Vision 60 mechanical dog—an animated, headless, mechanical sawhorse of sorts that manufacturers claim will one day be able to do everything real dogs can do, only better—and with enhanced lethality.

Hammer, 375th Security Forces Squadron military working dog, sits next to the Ghost Robotics Vision 60 at

Hammer, 375th Security Forces Squadron military working dog, sits next to the Ghost Robotics Vision 60 at

Scott Air Force Base, Ill., Dec. 17 2020. The Vision 60 robot’s ultimate capability is to preserve life.

(U.S. Air Force Photo by Airman 1st Class Shannon Moorehead)

In a recent exercise, a robo-dog provided targeting data to Air Force personnel and computers on the other side of the country. “Our robot was part of the kill chain and provided real-time strike targeting data to USAF operators,” a representative of the company told an online publication called The War Zone. “It was connected by a Silvus mesh radio to a network that had a battleship off the coast of Pensacola and a Starlink satellite connected to it.” Such operations will prove more exciting, said the representative, “once we get the cost of these systems down to where you could drop hundreds [of them] onto a battlefield.”

*

In the 19th Century, the United States War Department experimented with using dromedaries as pack animals in the deserts of the American Southwest. Army Lt. Edward Beale used 24 camels in his successful survey of a route from New Mexico to California, trailblazing part of what was to become Route 66. Despite Beale’s enthusiastic endorsement, many military men found the animals difficult to deal with. It was said that the camels smelled awful, could be unbelievably stubborn when they felt they’d been slighted, and had a nasty habit of spitting at people they disliked.

*

Gunpowder ended the age of the horse. But it did so only gradually. Despite the increasing firepower they faced from the 15th Century on, riders could still advance against artillery due in large part to the compulsive herd instinct of horses. Readers can find any number of accounts of wounded horses—bristling with arrows, burned, shot, dragging their own intestines beneath them—struggling to stay with the group. Human exploitation of this instinct allowed the mounted charge to survive well into the 20th Century. French cavalry, for example, captured a German airport in 1914—l’un des faits d’armes le plus heroiques de la cavalerie au cours de la grande guerre, as an exhibit at France’s Musee de l’Armee in Paris puts it. An Australian mounted assault wrested the town of Beersheba from Turkish occupation in 1917.

*

Despite the constant cruelties, there were always expressions of devotion between men and animals. The historian H.H. Scullard states that after the Roman victory at Zama in 202 B.C., distraught Carthaginians wandered the streets of their humbled city calling aloud the names of their lost battle elephants, as if by doing so they could summon them back.

*

During the Second World War, the United States Army spent substantial time and money on a scheme called Operation X-Ray. Thousands of bats were to be captured and stored in freezers, where the intense cold would force them into a deep, hibernation-like sleep. While the bats slept, technicians would sew small incendiary devices to their chests. The bats would then be loaded into canisters, which military aircraft would drop on Japanese cities. The canisters would open at around a thousand feet above the earth, at which point the revived bats—bat kamikazes, of a sort—would head for the cracks and crevices of the nearest man-made structures and attempt to chew off the bombs. This would detonate the devices, resulting in scores of building fires in populated areas.

*

Despite technological advances, animals are not exempt from military service even today. The Mujahedeen of Afghanistan rode horses while battling the mechanized forces of the Soviet Union in the 1980s. Some 3,000 dogs are currently on duty with American armed forces. A German shepherd accompanied the Navy SEALs who killed Osama bin Laden. And until recently the Swiss kept a huge number of military carrier pigeons—some 31,000, by one account—on hand in case of widespread electric outages as a result of attack.

*

The Navy’s Command Control and Ocean Surveillance Center in San Diego has, according to the New York Times, “worked with killer whales, pilot whales, and sea lions . . . . The Navy uses the animals to retrieve unarmed test torpedoes. Sea lions can dive up to 600 feet, while whales have been used to bring back sunken objects from 1,000 to 1,500 feet. The whale program fell out of favor, however, because the animals are so difficult to transport to the retrieval location.” The Navy has also reportedly attempted for years to turn dolphins into deep water commandos. Dolphins are believed to be highly intelligent. According to one Navy veteran who worked with the animals, they often refuse to follow orders. This may be part of the reasoning behind the Navy’s reported plans to retire its mine-detecting dolphins in favor of “sonar robots.”

*

Whether one believes that animals will play a large role in future conflicts depends in part on one’s definition of “animal.” Microbial creatures have been cultivated to fill the armories of an indeterminate but probably growing number of nations. Bacillus anthracis—the anthrax bacterium—causes an infectious, usually fatal disease in cattle and sheep. Characterized by ulcerative skin lesions, the disease can be transmitted to humans and is highly lethal. In a genetically engineered state of heightened “effectiveness,” it is said to be a prime candidate for use in biological warfare. The Soviets are rumored to have dosed their German opponents with an airborne form of tularemia during World War II. Japan’s infamous Unit 37 reportedly developed a “flea bomb” that spread the bubonic plague in China during the same war. Other possible bacterial payloads include typhus (bacteria of the genus Rickettsia), cholera (Vibrio cholerae), and botulinum (Clostridium botulinum). Like the elephants used in warfare 2,500 years ago, microbes are difficult to control once released.

*

The cessation of mass slaughter of animals in warfare was unintentional. It has resulted from technological advances rather than from an effort to alleviate the suffering of what some in the 19th Century called “dumb brutes.” Eliminating the physical involvement of animals in our wars is a fine, if accidental achievement. Though we all may benefit from ceasing our reliance on these indifferent allies, our history of conscripting animals symbolically and physically during times of war is pervasive.

Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) of the NMMP on mine clearance operations, with locator beacon. K-Dog, a bottle-nose dolphin belonging to Commander Task Unit (CTU) 55.4.3, leaps out of the water in front of Sgt. Andrew Garrett while training near the USS Gunston Hall (LSD 44) in the Persian Gulf. Attached to the dolphin’s pectoral fin is a “pinger” device that allows the handler to keep track of the dolphin when out of sight. CTU-55.4.3 is a multi-national team consisting of Naval Special Clearance Team-One, Fleet Diving Unit Three from the United Kingdom, Clearance Dive Team from Australia, and Explosive Ordnance Disposal Mobile Units Six and Eight (EODMU-6 and -8). These units are conducting deep/shallow water mine countermeasure operations to clear shipping lanes. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 1st Class Brien Aho. This image was released by the United States Navy with the ID 030318-N-5319A-002)

Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) of the NMMP on mine clearance operations, with locator beacon. K-Dog, a bottle-nose dolphin belonging to Commander Task Unit (CTU) 55.4.3, leaps out of the water in front of Sgt. Andrew Garrett while training near the USS Gunston Hall (LSD 44) in the Persian Gulf. Attached to the dolphin’s pectoral fin is a “pinger” device that allows the handler to keep track of the dolphin when out of sight. CTU-55.4.3 is a multi-national team consisting of Naval Special Clearance Team-One, Fleet Diving Unit Three from the United Kingdom, Clearance Dive Team from Australia, and Explosive Ordnance Disposal Mobile Units Six and Eight (EODMU-6 and -8). These units are conducting deep/shallow water mine countermeasure operations to clear shipping lanes. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 1st Class Brien Aho. This image was released by the United States Navy with the ID 030318-N-5319A-002)

Warriors imagine themselves as lions and hawks, eagles and wolves. We call our weapons Panzers, Falcons, Sidewinders, Cobras. Flight crews emblazon their aircraft with fearsome teeth (think of Claire Chennault’s “Flying Tigers”). Says Sun Tzu in The Art of War: ” Strike the enemy as swiftly as a falcon strikes its target. It surely breaks the back of its prey for the reason that it awaits the right moment to strike.”

*

As we learn more about the natural world and rely increasingly on the sort of faceless electronic wizardry that allows our weapons to kill at locations hundreds of miles away, we’ve come to realize that none of the animals we like to identify ourselves with actually engage in the calculated mass murder we call war. In fact, the closest animal analogy to human warfare is carried out only by a few types of insect—or, in certain instances, groups of primates.

Only through ridding ourselves of our anthropomorphic fantasies may we hope to lessen the persistent allure of armed conflict.

Bruce McCandless III

Bruce is an attorney and writer who lives in Austin, Texas. He is the author of the novels The Black Book of Cyrenaica, a supernatural thriller based on the North African campaign of General William Eaton in 1805, and Sour Lake. All of This is Ours, a book of his poems, will be issued in April of 2021 by Grayson Books, and he is currently working on a history of NASA during the Apollo, Skylab, and Space Shuttle programs titled Wonders All Around, scheduled for release later this year.