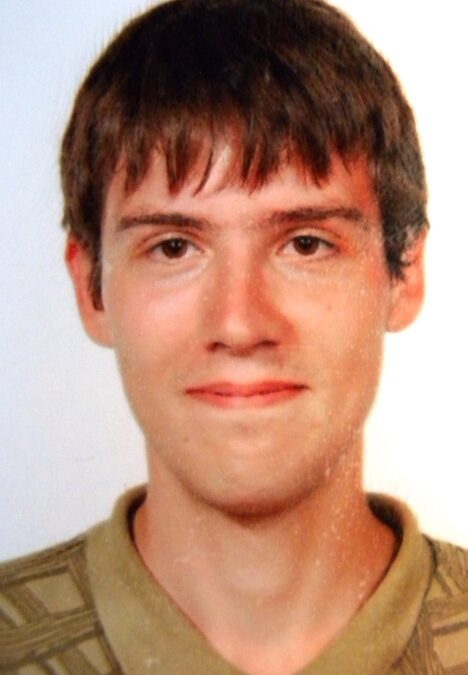

Jan Philip was a Swedish student studying in the US before journeying to Colombia.

Image courtesy of Jan Philip’s family.

Watering the plants on my sunny Bogotá balcony, the phone rang. It was a delegate from the Colombian commission of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

“We have the body. We’re heading up the river,” said the female voice before the line abruptly cut off.

So ended the two-year search for Jan Philip Braunisch.

The Swedish traveler had been abducted, beaten, and shot by FARC guerrillas in May 2013 in the notorious Darien Gap, the mountainous jungle that efficiently plugs the narrow isthmus between Colombia and Panama. Jan Philip’s death was just a coda in the decades-long conflict that pitched left-wing rebels against right-wing death squads with cocaine cartels and a US-backed state military.

But why? The rebel army had rules and were rarely reckless and poised to make peace with the Colombian state. The killing seemed as pointless as it was brutal. It would take two years to recover his remains. And many more to get answers. And even then, justice would remain elusive, as it has been until today.

The Last Post

Jan Philip was a brilliant math student, tough and well-travelled. In his mother’s words, he was “fearless and determined.” He had already made shoestring journeys across West Africa and Asia.

The twenty-six-year-old spoke Chinese, some Arabic, Spanish and French, and was studying statistics at Purdue University in the US, from where he flew to Bogotá to start his adventure to Panama and beyond. All this before returning to Europe for a PhD.

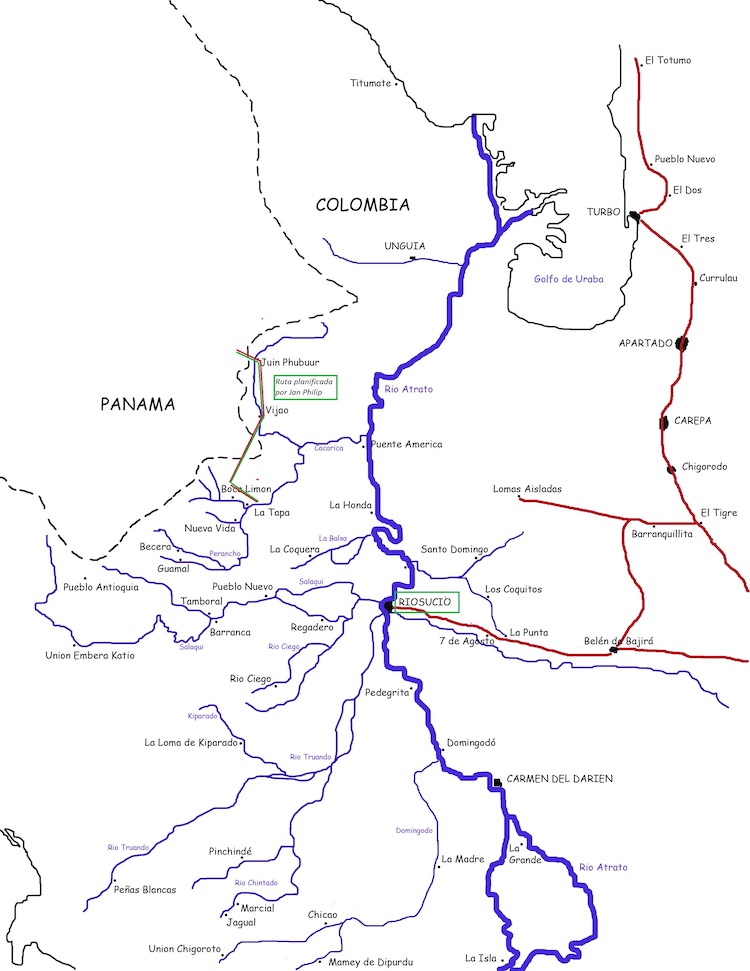

He crossed Colombia in a matter of days, arriving in the small city of Quibdó, in the Chocó region, where the road ends and onward travel is fluvial through jungles and swamps. He pushed on by boat down the Atrató River, arriving at sunset in the remote town of Riosucio after a twelve-hour odyssey. The young Swede was tired and dirty, but also upbeat: he was getting closer to his goal, the Darien Gap.

The Atrato River is the main fluvial transport link for communities in the Chocó region of Colombia,

The Atrato River is the main fluvial transport link for communities in the Chocó region of Colombia,

but also flows through some wild and lawless areas. Photo by Steve Hide

In Riosucio, Jan Philip would have stood out in the rickety town built on stilts over a swirling river. He was tall, with a sparse frame, cropped brown hair and round glasses. Local people in town were mostly Afro-Colombians, but canoes pulling into the riverside port would be mostly indigenous from Embera and Wounan villages, the women with colorful print dresses and the men in football shorts, some sporting boars-teeth necklaces. Not many tourists make it to this corner of Colombia.

He called at the priests’ house, the Casa Cural, looking for food and lodging. The Jesuit fathers gave him dinner and directed him to a nearby hotel. “He was asking about walking routes to Panama. That was unusual,” one of the missionary priests would later tell me.

The priests often helped the migrants who trekked across the Darien Gap guided by coyotes, people smugglers, on their journey to North America. Tourists wouldn’t take this route, explained the priest, but the Swede was “very determined.” They helped him find a canoe that next day would carry him up the smaller rivers to Panama.

Next morning, on May 15, 2013, Jan Philip found an internet café where he sent a last email to his wife in Sweden and updated his travel blog. It was his last post.

“I’m in Riosucio now. From here it’s not far to Panama. There are supposedly quite many paths. We’ll see how it goes.” Then he vanished.

Jan Philip was a Swedish student studying in the US before journeying to Colombia.

Jan Philip was a Swedish student studying in the US before journeying to Colombia.

Image courtesy of Jan Philip’s family.

The Impossible Task

Jan Philip’s disappearance was a waking nightmare for his family back in Sweden. With no news with each passing day, and no progress by the authorities to find him, the months dragged on. In September, four months after that final message from Riosucio, the family agreed that his wife, Shiwen, should fly to Colombia to search.

Shiwen, who had met Jan Philip at university in Sweden, spoke no Spanish and had little knowledge of South America. The family asked me for help. Could I host her in Bogotá?

I lived in Colombia and had worked for a medical NGO in Riosucio and visited villages in the Darien Gap. Still, I was cautious. This was a lawless territory with minimal state presence. Anyone following Jan Philip’s footsteps might equally disappear.

Shiwen was not put off. Despite numerous warnings not to travel from the Swedish authorities, she boarded her plane. The next day I scooped her up at Bogotá’s airport.

The small town of Riosucio is the jumping-off point for the Darien Gap. We know Jan Philip dined with the missionary priests here in the Casa Pastoral the night before he disappeared. Photo by Steve Hide

The small town of Riosucio is the jumping-off point for the Darien Gap. We know Jan Philip dined with the missionary priests here in the Casa Pastoral the night before he disappeared. Photo by Steve Hide

News of a Killing

“Be prepared for a very long and frustrating wait. Any resolution could take years,” Shiwen was warned by an official at the Swedish Embassy in Bogotá, one of many meetings we crammed into her two weeks in Colombia’s capital.

We had to start somewhere. In the chilly Andean capital, eight hundred miles from where Jan Philip disappeared, I prepared a list of contacts and started to work the phones. I knew people in the Chocó living along the river, a cocaine corridor controlled by drug gangs and rebels. A place where the wrong phone call can get you killed. We had to be discreet.

Several messages came back quicker than expected: “The Swede? They killed him. Everyone on the river knows. He’s dead.”

It was devastating news, but not that unexpected. Four months was long past the due date that an armed group would keep a hostage without claiming ransom. Silence was an ill omen.

Other messages were the same: the mono had been killed, but no-one could say why, or by who.

“The word has come down that if anyone talks, they’ll suffer the same fate,” said one contact. Another one told me bluntly: “Don’t call again,” with terror in his voice.

These reactions were painting a picture: Jan Philip had fallen foul of Colombia’s dark side, the violence that for most people inhabited movies and telenovelas, but in the Darien Gap was all too real.

For Shiwen, pitched into a world of crazy conspiracies and undercover meetings with secret contacts, this was a long way from Sweden. But she took it in stride.

“We need to be sure. And we need to get him back,” she said.

Missing Poster created by Fiscalia de Colombia In September 2013, four months after he went missing, the Swedish and Colombian authorities sent missing posters to communities in the Chocó, which started information trickling back.

Missing Poster created by Fiscalia de Colombia In September 2013, four months after he went missing, the Swedish and Colombian authorities sent missing posters to communities in the Chocó, which started information trickling back.

The Missing

Hearing that someone’s dead, and proving it, are two different things. For now, according to official files kept by the Fiscalia, the Colombian prosecutor’s office, Jan Philip was the victim of desaparición forzada, forced disappearance, as of May 15, 2013.

The phrase has a particular resonance in Colombia where armed groups of all stripes have long practiced the cruel art of making people vanish. This started with the drug cartels and was perfected by paramilitary gangs such as the powerful AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia), who even went as far as to build industrial crematoriums to vaporize peasants in some conflict areas.

Others were buried in remote places or bound in barbed wire and sunk into rivers or lakes. In 2023, more than one hundred thousand Colombians were still declared missing from decades of internal conflict, with fifty-three hundred suspected mass graves sites waiting to be investigated.

These disappearances had various goals: to keep the body count low, protect perpetrators—with no remains it’s hard to open a case—and control communities through psychological torture. With nothing to bury and mourn, families were left in a limbo of grief.

Over the course of decades in Colombia, thousands of families lost brothers, sons, daughters, fathers, mothers taken away by masked men, or stopped on the road or river and marched into the swallowing jungle, never to be seen or heard from again. Jan Philip was one drop in a sea of sorrow.

A Bad Place to Disappear

How to proceed? If Jan Philip had been murdered, as we suspected, then the perpetrators were unlikely to cooperate. The Fiscalia was on the case, but its investigators had only limited access to conflict zones since, as state agents, they were themselves targets for drug gangs and armed groups. At some point we would need to contact the armed groups directly.

That was doubly difficult in the Darien Gap, labelled “the most dangerous place on Earth,” a narrow isthmus—120 miles across at its narrowest stretch—connecting South and Central America and known for its extreme geography and presence of drug gangs.

Like much of Colombia, the Darien was a mosaic of safe and unsafe zones, with no clear demarcation. The coastal strip along the Caribbean even had popular beach resorts. I had my honeymoon there.

Any inland route, though, was a bad place to disappear. To reach it you needed to take a canoe through labyrinths of swamps choked by lettuce-like vegetation, pushing with poles while swatting off the tapas, biting triangular flies.

Once through the swamps, there were flooded forests to cross, often requiring a machete to clear a path, before punching up fast-flowing streams into a steep mountain range coated in thick jungle with spikes, spines, bugs, snakes, poisonous frogs, all bathed by a whopping five hundred inches of rain a year that could sap your strength and wash you into ravines. From there a maze of paths might—or might not—lead you to Panama, where conditions were no better.

Flying into the Darien Gap, with a view of the spine of jungle-clad hills that forms the boundary between Colombia and Panama. Photo by Steve Hide

Flying into the Darien Gap, with a view of the spine of jungle-clad hills that forms the boundary between Colombia and Panama. Photo by Steve Hide

Guerrillas in Their Midst

The jungle and cloud cover of the Darien made it a natural hideout for the FARC, the left-wing revolutionary armed forces of Colombia, who had been fighting the state for fifty years. Their 57 Front had several hundred seasoned fighters that patrolled the rivers and trails, and manned checkpoints from where they controlled the flow of cocaine, guns, and human migrants over the frontier.

To protect the zone, the FARC would sow mines and booby traps across strategic routes and have fighters ready to ambush any rival forces who might encroach. This was backed by a vast network of informants and urban collaborators, called milicianos, in local towns and transport hubs.

The guerrilla fighters themselves lived in camps hidden deep in the rainforest of both sides of the border, often shifting at short notice. Their weak spot was their reliance on a fragile collaboration with local villagers for supplies of fuel and food.

The Darien’s strategic value to the FARC also made it a top target for rivals such as the Clan de Golfo, a powerful drug gang made up of paramilitary fighters, and the Colombian military itself that would harry the guerrillas on the main rivers with Piraña gunboats and strafe jungle camps with low-level attack planes.

Such a life, in such harsh conditions, required a certain ideological dedication. Many 57 Front fighters were local Chocó people, used to the harsh conditions, and driven to a rebel life by decades of state abandonment in the region.

An Imperfect Peace Process

In 2013, when the Colombian state and the FARC sat down to negotiations in Havana, Cuba, the news echoed around the world: was this the end to the planet’s most intractable conflict?

Back in the Chocó there was nothing to celebrate, as everyone knew that talks between armed groups would only increase conflict in the short term as various sides levered position.

This reality, though, was brushed over by the world’s media, and I remember being surprised when friends and family overseas called me to laud the “peace” in my adopted country.

And then there was the bitter truth that a key smuggling route like the Darien Gap, vital to the multi-billion-dollar cocaine industry, would draw in competing factions vying to replace the FARC.

Meanwhile the peace process itself had plunged the FARC into internal struggle, with some units—particularly those more closely involved in the cocaine trade—reluctant to give up their hard-won benefits.

The rebels had always struggled to control their own far-flung units but were more polarized. For fighters at the spear tip, the Havana talks, held in cushy hotels, were just a retirement scheme for senior commanders while lower ranks were expected to give up their guns for dubious benefits in a hostile state.

This fragmentation created opportunities for the FARC’s enemies, with the Colombian military maxing out attack in key areas like the Darien where, shortly following the Havana talks, several guerrilla commanders were killed or captured, and guerrilla camps bombed by the air force.

Even in their jungle redoubt, the 57 Front was vulnerable and under constant attack. And as usual, civilians would be caught in the crossfire.

“It’s hot, very hot, people are scared, and no-one knows who to trust,” a contact told me at the time.

Jan Philp knew nothing of this. His compass was set to the Darien Gap, and walking to Panama, and nothing would deter him from his path.

A hand-drawn map showing the lower Atrato River and border with Panama,

A hand-drawn map showing the lower Atrato River and border with Panama,

and the suspected route of Jan Philip. Map created by Steve Hide

A “Pirate” Boat

Back in Bogotá, the search for Jan Philip had got off to a shaky start: the Swedish Embassy only declared him missing after four months, and the Colombia state investigators even cast doubt he had disappeared.

“People sometimes go missing on purpose,” a Fiscalia detective told me by phone. Paolo (note: not their real name) was working the case from Quibdó, the regional capital and closest city to the Darien.

Paolo believed that Jan Philip had intentionally gone off the radar and joined the FARC, with the rumors of his death self-generated to throw us off the trail. The theory wasn’t crazy: foreigners had joined the FARC, such as a Dutch woman who became an active guerrillera after falling in with the rebels in 2007 and became a celebrity in her home country (though less popular in Colombia).

Fueling this idea was a lack of any hard evidence that Jan Philip ever arrived in Riosucio. “We can’t find Jan Philip’s name on any boat manifests in Quibdó,” Paolo explained to me. Police had scoured the passenger lists that boat captains submit to the riverport authorities before any voyage on the Atrato. The Swede never appeared.

And in Riosucio, the small town where Jan Philip would surely stand out, there was no sign. The Fiscalia found an eyewitness to someone who vaguely matched the description of Jan Philip. But this foreigner was seen carrying a computer tablet, something the Swede did not have.

Quickly, though, Shiwen could counter the last point: Jan Philip was carrying a Kindle reader. Could this be the “tablet”? They look the same. Plus, she had personal emails from Jan Philip which described Riosucio. We sent a photo of the Kindle and translations of the emails to Paolo.

Armed with this data, Paolo dug deeper in Quibdó and came up with an amazing fact: Jan Philip had boarded a boat in Quibdó, but it was a cargo boat—Paolo called it a “pirate boat”—not authorized to carry passengers. Hence no name on the passenger lists.

Looking back at his travel blog, Jan Philip wrote from Quibdó: “Taking the boat is ridiculously expensive, about US $70 from here to Riosucio.” Clearly he had found a cheaper option.

Quibdó waterfront, where Jan Philip set off down the Atrato River in May 2013.

Quibdó waterfront, where Jan Philip set off down the Atrato River in May 2013.

The small city is the capital of the Chocó region. Photo by Steve Hide

Traveling on the Edge

Clarifying these facts also gave us an open channel to the Fiscalia without compromising our own informants. Paolo solemnly agreed we could share our ideas without naming contacts (we used codes) and in return fed us the twists and turns of his own investigation.

News of Jan Philip’s pirate boat had been an eyeopener: here was a guy willing to go off script. Now was the moment to dive deeper into his blog.

Philip in Central America, written sparsely from on the road, described a helter-skelter rush across Colombia getting rides on trucks, sleeping in shacks, and sharing meals with families.

One of Jan Philip’s photos showing the family that hosted him in Quibdó. His minimalist traveling style meant he asked local people for food and lodging. Screenshot from Philip in Central America blog.

One of Jan Philip’s photos showing the family that hosted him in Quibdó. His minimalist traveling style meant he asked local people for food and lodging. Screenshot from Philip in Central America blog.

His spartan approach to travel was imbued with a core philosophy of being with (and trusting) local people and took him far from the “backpacker trail” of comfortable hostels and organized thrills. All this was done on a very tight budget: Jan Philip hitched or hiked wherever possible.

Such travel on the edge required careful packing, and his blog proudly displayed his kit with a small rucksack (which when full weighed under ten pounds), a lightweight jacket and long pants of synthetic material that was “good protection from bug,” a medical kit, a Kindle reader, a compass, camera, water bottles with purifying tablets, a flashlight, a basic wash kit, and just one change of clothes. His only footwear was a pair of sandals.

Perhaps to underline his travel ethos, Jan Philip emphasized the items “notably absent” from his packing, such as a guidebook: “they usually don’t contain any information you can’t ask the locals about!”

Jan Philip travelled light, but his choice of equipment also raised suspicion with the FARC guerrillas. Screenshot from Philip in Central America blog.

Jan Philip travelled light, but his choice of equipment also raised suspicion with the FARC guerrillas. Screenshot from Philip in Central America blog.

Red Flags

The flaw in this plan though was that while physically prepared for his adventure, Jan Philip’s gung-ho approach would not mesh well with Colombia’s complicated context. And his speed of travel—“nine countries in three months”—left little time to learn along the way.

And by his own admission he struggled to understand the local Spanish dialect (“I’m not used to the accent here”). This might partly explain how in Quibdó he got bad advice at the local police station: “I was honest to them about going to Panama over land, and they didn’t even say it’s dangerous or anything!”

A guidebook would have highlighted the safe routes to Panama, such as a short tourist trail linking the beach resorts of Capurgana and Sapzurro in Colombia and La Miel in Panama, and one that the police would assume the Swede was planning.

Then there were other red flags, such as his ninja image with a black rucksack, dark clothes, short hair, and minimalist kit. This unusual look for a tourist would likely tweak the antennas of drug gangs and armed groups with their spies everywhere.

Colombian jungles had a known presence of foreign special forces and mercenaries; British SAS had tried to take out Pablo Escobar, and US Drug Enforcement Agents were frequently deployed undercover. In the FARC’s increasingly paranoid state, anyone unusual would be painted as a target.

The coastal walking track from Sapzurro, Colombia, to La Miel, Panama.

The coastal walking track from Sapzurro, Colombia, to La Miel, Panama.

This is the safer tourist route. Photo by Steve Hide

A Monumental Mistake

In 2014, some captured guerrillas told Colombian investigators that the FARC’s 57 Front had killed Jan Philip “thinking he was a spy,” firming up our suspicions.

If it was true then the FARC had made a monumental mistake, even by their own standards. For all its tough reputation, the guerrilla group’s image was crafted around discipline and restraint, with careful selection of “political” targets as part of their ideological struggle against the right-wing state.

The strategy was successful. With eighteen thousand combatants, tens of thousands more political supporters, and cash flow from cocaine, the FARC fought the state military to a standstill over five decades and ruled over vast areas of rural Colombia.

To maintain this grip required strict hierarchy and rules, on the surface at least. I’d often crossed paths with the FARC in rural areas, they were usually smart, professional, and in control. Several times, I was detained by local commanders. Where was I from? they’d ask. What was I doing? Was I a spy? What did my parents do for a living? After a chat, they’d let me go.

Behind this façade, though, I knew the FARC could be brutal, detaining hostages for years—often lowly police and captured soldiers—chained up in jungle cages in the grimmest of conditions. The guerrilla group also attracted its fair share of criminals and misfits.

Even so, for them to kill Jan Philip was out of character, particularly with the start of the Peace Process. Any investigation would have revealed him as a tourist, and even if he was a spy, they could spin the situation to their advantage with a prisoner swap.

The question was, if they erred and executed an innocent person, would they admit it? Past form suggested the FARC would deny, delay, then deflect guilt from senior commanders.

In 1999 the FARC had murdered three US citizens, killings that were nonsensical since the three were indigenous campaigners invited by Colombian tribes to assist in resisting oil companies, a cause aligned with FARC ideology. After many denials—and revelations from intelligence sources—the FARC admitted the act but blamed a low-level commander claiming he “acted without authorization.” Other sources said the order came from above.

A Mysterious Map

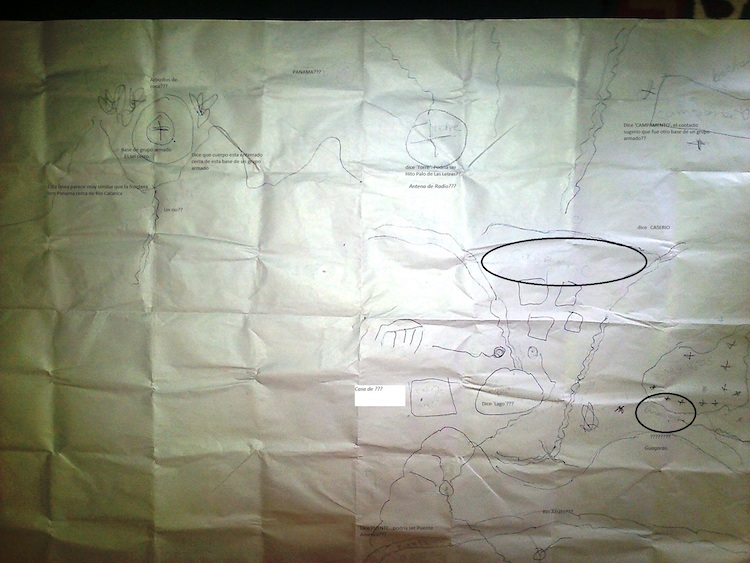

I was quite surprised then, when in early 2014 one of our key contacts in Quibdó walked into a scene straight out of Tom Clancy: an anonymous caller directed him to a backstreet on the outskirts of the city where a young female—“with all the look of a guerrillera”—unrolled the hand-drawn map on the floor, allowed him to take some photos, then took out a cigarette lighter and set the paper on fire.

“If you know the Darien, this map will guide you to the Swede’s body,” she said, as the ashes smoldered, before mounting a motorbike and disappearing down a side street.

It didn’t. Crude squiggles, signs, and annotations showed a village, some rivers, coca bushes, and what appear to be hidden camps. But it was too vague to find a person in the vast Darien Gap.

Still, on analysis, it was a sign, and maybe an important one. Someone in the FARC was reaching out. We had their attention.

A mysterious sketch map that was hand-delivered to a contact in Quibdó and then burnt.

A mysterious sketch map that was hand-delivered to a contact in Quibdó and then burnt.

The notes on the map are the author’s. Credit: Anonymous

“More Narcos Than Guerrillas”

By mid- 2014, the Darien Gap was falling further into conflict. There was a risk that FARC units would fracture and disperse, camps shift, and Jan Philip even more lost to the jungle, a fact reinforced by a Jesuit priest who recalled the challenges he had exhuming a body—a villager murdered by paramilitaries—in the Darien years before.

“We knew exactly where he was buried, but even then, it took days to unearth his remains,” he told me. “The rainforest shifts and swallows everything up.”

Time had run out. After consulting with Shiwen, I flew to the Chocó to deliver letters in the hope they would reach the 57 Front. We would appeal directly to the commanders, if there were any left.

I’d often worked in conflict zones, but this trip was different, and I was nervous as the prop plane landed at the small airport. The armed groups have informants everywhere and would not be pleased to see me.

In a safe house with my informants, I could relax. They would try and contact the FARC and report back, but it would take time. The guerrillas were in turmoil, they warned, and increasingly erratic. Many fighters had deserted, demobilized, or switched sides, and the remaining diehards were often at loggerheads with their own organization.

“These FARC dangerous. More narcos than guerrillas,” said one of my hosts. But they would try their best to deliver a message.

Letters to Havana

The strategy seemed to work, and a month later the FARC 57 replied through our intermediaries. “Killing the Swede was a mistake,” they said. “He couldn’t explain why he was here.” It seemed a half-hearted admission and an attempt to shift blame.

Then, over a period of several months, I received more calls and garbled messages with the story shifting again. Jan Philip had “slipped and drowned in the river.” Or he “had hit his head on a branch while in the canoe.” Then, “he had been forced to carry a cargo of cocaine over the border and died of heat exhaustion.”

Each was a plausible scenario but didn’t explain why the FARC hadn’t handed over the body at the time. It seemed they had something to hide. And anyway, the FARC had already bragged to the people on the river they had “killed a spy.” It was too late to back-pedal now.

Then a new avenue opened. A priest in the Chocó suggested we contact Havana, where the Peace Process was bearing fruit. Maybe the FARC negotiators could shake the tree with their rebels in the Darien Gap.

This was a possibility, and a logical one, though I suspected it had already been pursued by the Swedish government. But no harm in trying again.

My next mission was by bicycle across Bogotá (by far the fastest way to cross the congested city) to the heavily fortified compound that is the Catholic Church’s Colombia headquarters.

I soon found out why it was so secure: this was where the senior FARC commanders had hidden out, in the heart of the capital, during the “pre-talk talks” that proceeded the real deal in Cuba. The church had always been a moderator in Colombia’s conflicts, and moved in mysterious was, so this didn’t really surprise me.

A friendly priest heard my story and swung into action: he was traveling to Havana the following day and would ensure Jan Philip’s case would be considered. Meanwhile he gave me very specific instruction on letters we must immediately send to Colombia’s peace commissioners.

I sped home and quickly prepared the letters to email in time for his arrival in Havana. This, I felt, was our last throw of the dice.

A Meeting on the River

A week later, my phone rang, just as I was picking up the kids from school. It was an unfamiliar voice: “The body will be released. This is the number to call.” My heart raced.

Then I was back on bike, dodging traffic, to reach the International Committee of the Red Cross, where senior staff had promised to help if we ever got to this moment.

To my surprise, the head of ICRC was there to meet me along with the Protection and Forensic teams. I told them the story (which they probably already knew) and gave them the phone number—“Over to you guys now!” I remember saying. I went home and messaged Shiwen with the news.

Two weeks later an ICRC delegate called me from the Darien Gap: she was in a boat on the River Atrato, with the remains of Jan Philip, heading to Quibdó.

The Jungle Camp

Our worst fears were confirmed, but at last Jan Philip was found.

It made a difference. Shiwen had told me of recurring dreams: “Jan was walking in front of me like a shadow, but my hands could not reach him,” she said. “Every time I hugged him, he became air.” At last, those dreams would fade.

But there were still loose ends. Two years later, in 2017, Shiwen came back to Colombia. A lot had happened since her last visit.

Jan Philip’s remains were resting in Bogotá’s Gardens of Peace, where we strolled through green scenery and lines of crosses of other conflict victims. The Peace Process had concluded, and Colombia’s President Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Many FARC had demobilized, but others kept fighting, now called the Disidencias—the same tigers with new stripes.

In Bogotá we met with Paolo. The Fiscalia investigator had news, but most of it was unofficial as reports were yet to be written. He wanted to meet Shiwen in person and tell her what he knew.

While working another undercover case, by chance he met demobilized fighters from the 57 Front. They freely told him the story of the day Jan Philp was killed. It was a harrowing story, but we needed to listen.

Jan Philip had made it into the Darien Gap and was close to Panama when was intercepted by Roberto (note: not their real name), a mid-level FARC commander with a reputation for brutally extorting local communities and his unauthorized deals with drug gangs.

The Cacarica River, a tributary of the Rio Atrato, which flows down from the hills bordering Panama. We know Jan Philip took this route, which is closely guarded by guerrilla groups. Photo by Steve Hide

The Cacarica River, a tributary of the Rio Atrato, which flows down from the hills bordering Panama. We know Jan Philip took this route, which is closely guarded by guerrilla groups. Photo by Steve Hide

The seasoned fighter was increasingly paranoid, and on a constant hunt to root out spies and infiltrators, a situation that only intensified with increased air attacks against the rebels in the Darien. Sometime around 2012, he summarily executed two local villagers, accusing them of being army informants after a FARC camp was bombed.

For this, Roberto was punished and demoted, but still left in the Darien to sow terror along the river. Then he met Jan Philip, in May 2013. The Swede was marched to a jungle camp, beaten, interrogated, and searched. His Kindle caused suspicion; what was this strange device? Probably a GPS.

Roberto declared to the rag-tag remnants of his squadron that the Swede was “clearly a sapo for the DEA.” The choice of words was illustrative: the DEA was the US anti-drug agency involved in interrupting the cocaine trade, and only tangentially connected to the Colombian conflict.

Again, our informants were correct: Roberto was focused on his drug deals; more narco than guerrilla. He gave the order to his FARC fighters assembled around their captive in the jungle clearing: “you know what to do.” After several hours in captivity, Jan Philip was forced to his knees and shot in the head.

Aftermath

Was this the final story? Probably. The eyewitness accounts coincided with the autopsy report that showed a “violent death” from a head shot at close range, probably from a pistol, and bone alterations suggesting beatings prior to death.

Then, around the time Jan Philip’s remains were released from the jungle, Roberto himself disappeared, according to a single source from the Darien. We could never confirm this rumor, but the story went that the rogue rebel was “called to a meeting” by the FARC and never came back.

There was one more tale to tell. Years later, I got an unexpected message from a foreign war reporter. The journalist, who dipped in and out of Colombia’s conflict zones, had read about Jan Philip and wanted to meet for coffee.

In late 2013, he told me he’d been in Juin Phubuur, a Wounaan village of close to the Panama border, on the same route planned by Jan Philip.

The chief told him a strange story: months earlier, a European had unexpectedly arrived in the village, with talk of hiking to Panama. The tall stranger was popular and full of fun, spending three days in the village playing with the kids, goofing around, sharing food, and sleeping in hammocks. Then the FARC came and took him away.

I know Juin Phubuur, a beautiful village with traditional huts by a crystal-clear river, surrounded by jungle with toucans and squawking macaws. And just a short walk from the border. I was amazed to hear that Jan Philip had made it so far on his walk to Panama. And even sadder that, instead, he was lost to the Darien Gap.

The Wounaan village of Juin Pubuur, close to the Panama border, in a remote part of the Darien Gap. We have anecdotal evidence that Jan Philip made it this far and even spent a few days in the community, before being taken by the FARC. Photo by Steve Hide

The Wounaan village of Juin Pubuur, close to the Panama border, in a remote part of the Darien Gap. We have anecdotal evidence that Jan Philip made it this far and even spent a few days in the community, before being taken by the FARC. Photo by Steve Hide

Steve Hide

Steve lives in Bogotá, Colombia, and is a writer, journalist, NGO worker and former truck driver and tour guide. He regularly writes and blogs about life in this beautiful but, at times, dangerous corner of South America.