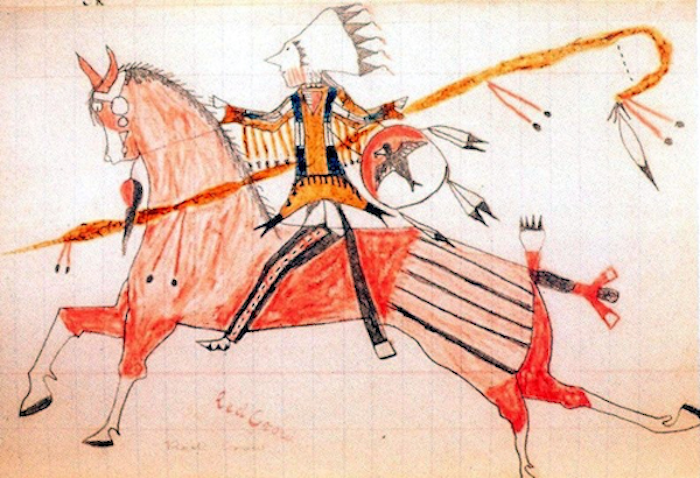

The Warrior Low Dog by Red Dog, Oglala Lakota, ca 1884, Wikipedia

As the United States expanded west during the nineteenth century, many Plains Indian painters were introduced to the high-quality paper used by bookkeepers known as ledger paper. The history of the period, as recorded on ledger paper by these painters, often followed the traditional forms used for painting on buffalo or other hide and expressed elements of Plains Indian history and culture of that period: battles for territory and survival, cosmic iconography, heraldic symbols, ceremonial traditions. John Pepion, a contemporary ledger artist who lives on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana, says:

“I see myself as a storyteller. Instead of a museum or institution telling us who we are, I’m telling our story to the world.”

In an article published in the journal Indian Country Today (October 30th, 2011), Chris Pappan, another painter interviewed in this feature, explains that a dozen or so of the most recognizable of these painters were prisoners of war following the period of conquest and genocide commonly referred to as the “Indian Wars.” “It’s political, “says Pappan. “A lot of the ledger art is basically prison art.”

(A version of these interviews originally appeared in the French journal Rumeurs (No. 4, February, 2018).)

John Isaiah Pepion, who hails from the Blackfeet Nation in northern Montana, is a leading ledger art painter. He holds degrees in Art Marketing and Museum Studies from United Tribes Technical College and the Institute of American Indian Arts, and his education continues with every piece he creates and every story he shares. He speaks with troubled youth in public schools to promote the benefits of art as therapy.

~

Peter Brown: The first time I encountered ledger art, one of my immediate responses was to the fact that the images had been imposed over accounting records; the heartbreaking image of a warrior riding into battle rendered over a sheet of railroad accounting figures seemed, in some way—I mean the very act of painting on this paper itself—an act of resistance, or a kind of victory, even revenge. Do you ever feel this way, that imposing traditional colors and designs on numbers (typically representative of US dollars) feels like a moral victory that you as a painter, or as a representative of a group of painters, continue to celebrate? What is the emotional quality or complexity of that victory?

John Pepion: I believe ledger art was a form of resistance to the U.S. Government in the 1800s because a lot of Plains Indians were forcefully incarcerated. A lot of the Plains Indian Warriors spent twenty-plus years imprisoned and eventually died locked up. They were able to draw their past lives on ledger paper that the U.S. soldiers gave them. They drew hunting scenes, battle scenes, courting scenes, medicine scenes, and a way of life that was changing while they were incarcerated. I also see ledger art as a form of cultural preservation. Designs, colors, and stories are being recorded through ledger art. I see myself as a story teller. Instead of a museum or institution telling us who we are, I’m telling our story to the world. They might have given us ledger paper but they will never take our stories away from us.

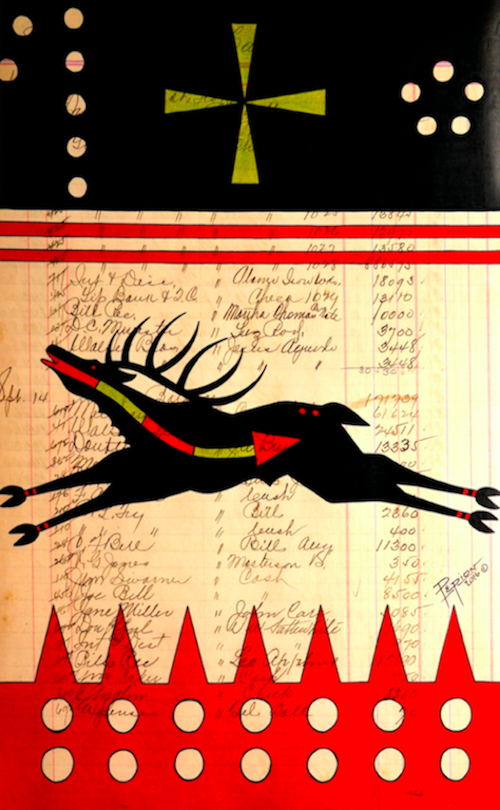

Elk Medicine by John Pepion

PB: I was just looking at an image of your magnificent painting “Elk Medicine” and was struck by the density and power of the colors and the motion of the forms; only on a third or fourth look did I realize you had been painting over the names of many people. I assumed most of them were European Americans who lived near the end of the 19th century, the period of war and genocide in the West, but I don’t really know that to be true. Most of them appear to have European names, but they could also have been Native Americans, African Americans, or Asian Americans. How, if at all, do those names affect you while are painting over them, or next to them? Would you have thought about them as individuals as you were painting? Are they meaningful to you in that way?

JP: I don’t purposely paint over any names and do admire the old writing of that time period. Nobody writes like that anymore. I do read the ledgers from time to time. Some are bank ledgers, accounting ledgers, and personal ledgers. I once came across a ledger where a person recorded the weather and what they ate every day. I would like to come across ledgers from my tribe. I know they exist.

PB: I grew up in NYC in a family of artists—my parents were painters who grew up in the West and Midwest—and I lived in Montana for seven years, but I only learned about this extensive and essential American art form in 1997, when I was forty years old. From what I know, you grew up in or near Browning. When you were a child, were Blackfeet people generally aware of the existence of ledger art? When and how did you learn about it? What were your initial responses to it?

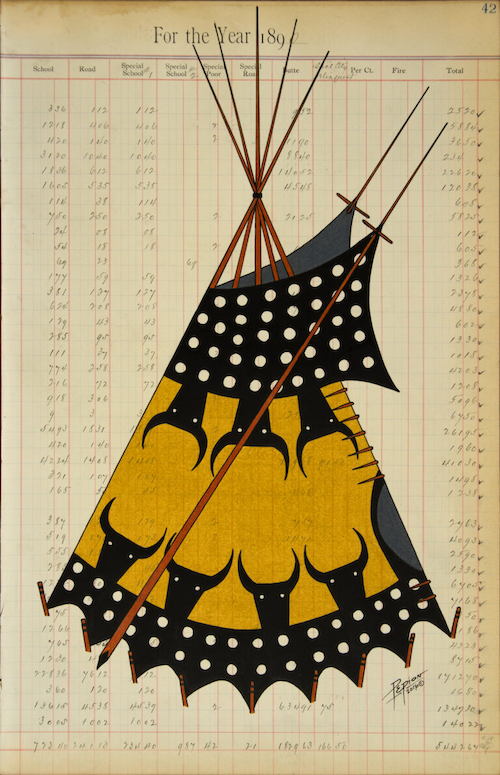

JP: I come from a family of artists. I can trace my family back to painting War Records and Winter Counts. Historians believe the style of ledger art first developed in Pictograph Rock Art and Hide Paintings and was later applied to paper. Ledger art is not a traditional form of Plains Indian culture. In the 1800s the U.S. Government introduced ledger paper to warriors being held prisoner for so called “Indian Wars.” I admire the old warriors who told their war records on hide. I also am a fan of the Plains Indian ledger artists of the 1800s. I prefer using antique documents such as ledger paper but not limited to just ledger paper. I also paint on rawhide, buffalo skulls, and actual tipis. I also do murals. I call my style of art “Plains Indian Graphic Art.” There are ledgers from Piikani (Blackfeet) from the 1800s as well.

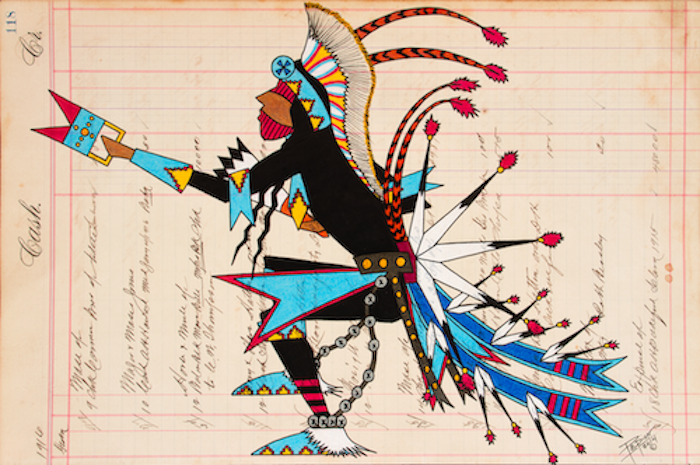

Champion Chicken Dancer by John Pepion

PB: Would you give us a description of the symbolism at work in paintings like “Little Otter Woman Makes Berry Soup,” “Champion Chicken Dancer,” and “Piikani Tipi”? Are there other paintings whose symbolism you would like to describe?

JP: My symbolism represents identity. Once you see my style of ledger art you will know it is Piikani. We are known for geometric designs mostly representative of the Rocky Mountains in Montana and Canada. Also symbols of our creation stories, like “Morning Star.” We believe that the Sun married the Moon and Morning Star is their Son. You will see the cross-looking symbol (Morning Star) throughout my work, especially on the back of tipis. The Sun is very important to Piikani culture as well and you will see that in my art.

PB: The ledger paper generally appears to be from the late 19th century and early 20th century. Where do you find it? Is it hard to find?

JP: I prefer paper from the 1800s and from Montana. It’s not hard to find. You can find it in antique stores, online, and people trade ledger paper. When I do shows, people who find out I’m using ledger paper realize they have some among their family keepsakes. They usually will gift me some old paper from Montana, too.

PB: How do you prepare the paper before you paint on it? Do you draw on the paper with pen or pencil before you begin to paint?

JP: I draw on the paper with pencil, then with ink, and color pencil. I go over the black ink lines last.

PB: What kinds of paints do you use? Are they traditional pigments and mixes or do you use commercially available paints? What kinds of paint?

JP: I use a drafting pencil, archival ink, and oil-based color pencils.

PB: What things would you want people who know very little or nothing about Plains Indian art to understand about your paintings? About ledger art in general? Is this distinct from what you would like other Native Americans to understand?

JP: As Native Americans or Indigenous People, we all have an understanding of our struggles and continue to fight to move forward. That includes moving forward with art.

Little Otter Woman Makes Berry Soup by John Pepion

PB: Other Blackfeet?

JP: I don’t speak for all Piikani. I do however have a voice through art. I will continue to learn and grow using my voice.

Piikani Tipi by John Pepion

Piikani Tipi by John Pepion

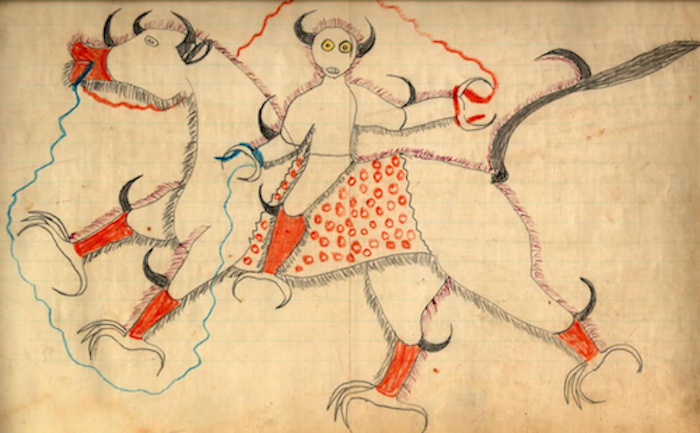

PB: On the ledger art wiki page, there is a famous drawing by the Lakota artist Black Hawk dated 1880 depicting a “horned Thunder Being on a horse-like creature with eagle talons and buffalo horns.” I find this to be a very masterful example of ledger art from the early days. I consider it a masterpiece of American drawing, but my response to it was simply a response to a great drawing—its beauty, the precision and vivacity of the representation, the balance in the colors and in the composition, the weight and lightness of the figure, the violence in the horns and talons, its emotional power. I responded to it with no a priori understanding of the system of symbolism and, therefore, the meanings of the symbols are distant to me. I know, for example, nothing about the Lakota Thunder Being or the rainbow that represents the entrance to the Spirit World. When a Native American viewer considers one of your drawings, do you hope or expect that a knowledge of the symbolism is immediately available to them? Is this symbolism included in an immediate visceral response to the drawing, as much of the symbolism in a Renaissance painting might be for a European viewer? Or does the symbolism get understood intellectually, secondarily? Is your painting also a way of educating Native Americans about the symbolism inherent in their own culture?

JP: When I do see that specific ledger by Black Hawk, I automatically think of his visions. He was a dreamer and had power. Most of today’s Plains Indian ledger artists can trace their lineage back to medicine people. I love to dream. That’s how I’m able to come up with my pieces. My art is inspired from Piikani stories and culture. Our ceremonies are alive and our language is still spoken. I myself participate in ceremonies such as the Thunder Pipe openings. I have an understanding of our language but I don’t speak it fluently. I’m also inspired by other people’s stories and personal life experiences. Like I mentioned earlier, when you see my art, you distinctively know it is Piikani. I believe I have a gift from the Creator and it shows through my art.

Thunder Being by Black Hawk, ca. 1880, Wikimedia Commons

Thunder Being by Black Hawk, ca. 1880, Wikimedia Commons

PB: Being entirely uneducated in the symbolism of Plains Indian art and culture, how incomplete would consider my response to Black Hawk’s drawing to be?

JP: It’s fair enough and I understood your questions. I myself know of Lakota Thunder Beings and Elk Dreamers but I’m not an expert and never would claim to be.

Chris Pappan is an American Indian artist of Osage, Kaw, Cheyenne River Sioux, and European heritage. A graduate of the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe and a nationally recognized painter, Chris calls his art “Native American Low Brow.” He exhibits in several Native American art shows and markets including the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Heard Indian Fair and Market, and the Eiteljorg. He resides in Chicago with his wife Debra Yepa-Pappan and their daughter.

Chris Pappan is an American Indian artist of Osage, Kaw, Cheyenne River Sioux, and European heritage. A graduate of the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe and a nationally recognized painter, Chris calls his art “Native American Low Brow.” He exhibits in several Native American art shows and markets including the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Heard Indian Fair and Market, and the Eiteljorg. He resides in Chicago with his wife Debra Yepa-Pappan and their daughter.

~

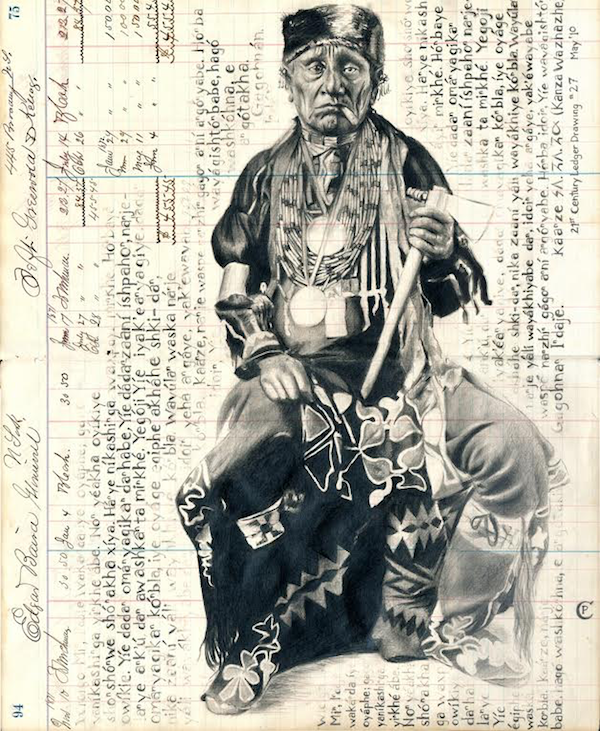

Peter Brown: I think that in many of your drawings and paintings you go farther than other ledger artists in your tendency to manipulate your media, that is, the paper itself; you use collage, you erase underlying text, your figures are elaborately rendered, highly individualized representations. Your approach adds layers of complexity to an art tradition that is often so powerful, expressive and elegant thanks to its simplicity. How do you think about this complexity? Is complexity something you think about at all as you work? Do you aim for it?

Chris Pappan: The complexity is certainly intentional, and part of it is a direct influence of George Flett. He took the genre in a new direction through his use of “traditional” imagery and combining it with Eurorealism, collage, embossing, etc. Another influence would be contemporary American pop culture (particularly “lowbrow”) because I wasn’t raised on a reservation and am learning about my culture through the research for my artwork, while simultaneously being accepted back into the fold of my Native community (the Kaw nation or Kanza people). While I understand your point about the elegance in the simplicity, I would have to disagree with that as being a blanket statement for the genre. There are many examples of pieces that are quite complex in their compositions and renderings. There are many battle scenes that are chaotic due to the nature of the violence that took place. The details with which figures are rendered give the viewer specific information about the individuals whether it’s a particular design on a shield, weaponry, hairstyles, etc. I also think this complexity exemplifies the complexity of Native American people.

Kanza-Osage by Chris Pappan

Kanza-Osage by Chris Pappan

PB: I feel fairly confident in saying that ledger art often feels like an explicit artistic answer to an imperial occupation. I’m tempted to say that, on some level, it is an effort at reversing the occupation. Could that be true? On what levels of experience could that be true?

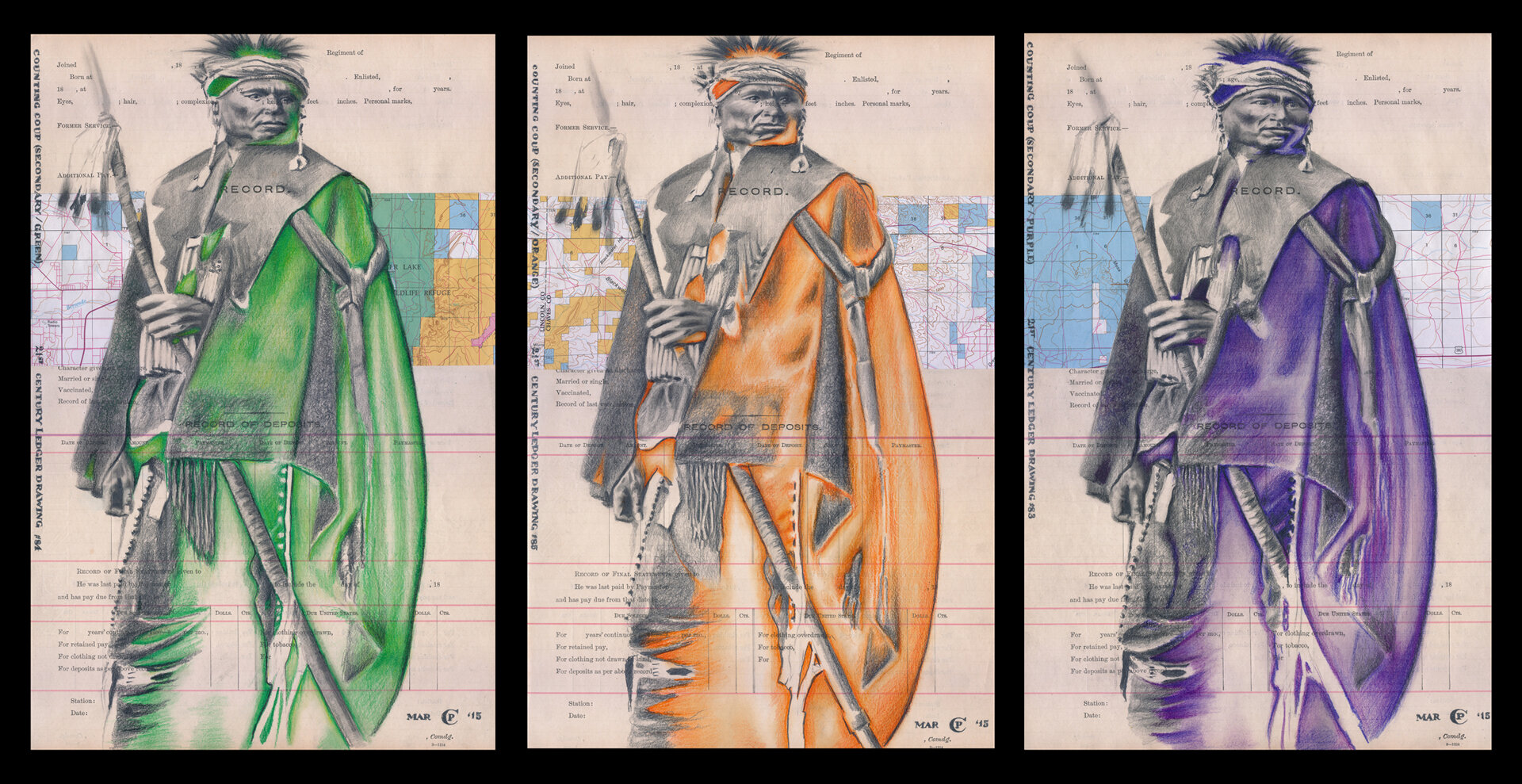

CP: I believe the substrate is sometimes just as important as the imagery. Case in point: there is a Lakota language bible in a museum in Munich, from the late 1800s that is filled with drawings done directly on the pages. If those images were done on some other paper or sketchbook say, I don’t think the feelings or emotions would be as powerful. Whether it was intentional or not, the statement of resistance, resilience and pride imbued in those works is transcendental. In my own work there are definite subversive elements, mainly due to the material or substrate. One of my first acquisitions of ledger paper was a US Cavalry recruitment ledger book. Any works that I create on that paper always feel to me like I’m counting coup. That book was used to help recruit people to do our ancestors harm, to forcibly remove us from our homelands; a tool of genocide. Yet, here I am, seven generations later, creating artwork on those pages, depicting the very same people the Cavalry was trying to exterminate.

Counting Coup by Chris Pappan

Counting Coup by Chris Pappan

PB: I hope I am not oversimplifying in saying that some Plains Indian people thought of time as fundamentally cyclical in nature. Ledgers, on the other hand, seem to me an expression of linear time, of mutual responsibility (debits and credits) quantified and elaborated according to a calendar that marches doggedly in a single linear direction, where whatever is due comes due according to that fixed order. Not all of your paintings of course are done on ledgers, technically speaking, but it seems to me that the notion of a ledger, an imposed order, underlies your paintings as well as those of many other ledger artists. You also attach maps in a collage-like fashion to many of your ledger paintings. It seems to me that, analogously, maps may be understood as an imposition of a spatial order on territory, a powerful but possibly arbitrary imposition (from a Native American perspective) of a kind of foreign metadata on the territories: mile markers, route numbers, latitude and longitude, etc. Adding maps as imagery to a ledger sheet allows you to express the political occupation in both space and time. Ledgers make a claim on history. Maps make a claim on territory. What do you think of that interpretation?

CP : You hit the nail on the head with that observation! That is precisely my intent for including the map elements in my pieces. I feel they are just as controversial or intriguing and I consider them to be a ledger of the stolen lands. I recently completed a piece that incorporates a map of the White Sands proving grounds (where the first tests of the A-bomb happened). I also try to use maps that highlight important Native American spaces in either a current or historic context like The Battle of Greasy Grass (aka Little Big Horn) or current reservation boundaries, which then may depend on a specific narrative in a work I might try to convey; or it could be important to my own personal narrative. Sometimes it can be arbitrary as well (perhaps a reversal of the arbitrary imposition you mention?) but the fact remains that in this country this is all Native land and will remain as such.

PB: Maybe painting over a ledger, covering it with paint, lines, glue, imagery, symbolism, and portraits, or just erasing the names and numbers on the ledgers is a way of regaining lost history and territory, at least in an emotional or symbolic fashion. Do you think this way of thinking about it, to some extent, explains the popularity of this art form among Native American artists?

CP: I have certainly thought this way about a specific drawing that I did, which was about the loss of language and conversely its revitalization and the awareness of the importance of retaining one’s language. That piece was then used for the cover of a Kaw language lesson book. But again, I see it as counting coup. By taking something from an adversary then repurposing it (in this case ledgers and maps) to tell our own stories and force the viewer to come to terms with the fact of our continued existence. I should also point to an intervention I did at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. There could be a whole other interview about that, but for now I will just say that I eventually approached that project as I would any of my drawings or paintings: I thought of the outdated (and poorly maintained) museum hall exhibit as my historical substrate. Working directly over the display cases with semi-transparent decals of my drawings, as well as video installation, sound and other works, I was able to confront visitors with contemporary representations of our culture and existence. Some people were confused because they literally think we are extinct, but the erasure of the misinformation in the exhibit hall was a monumental turning point in my career and a victory for Native people I think.

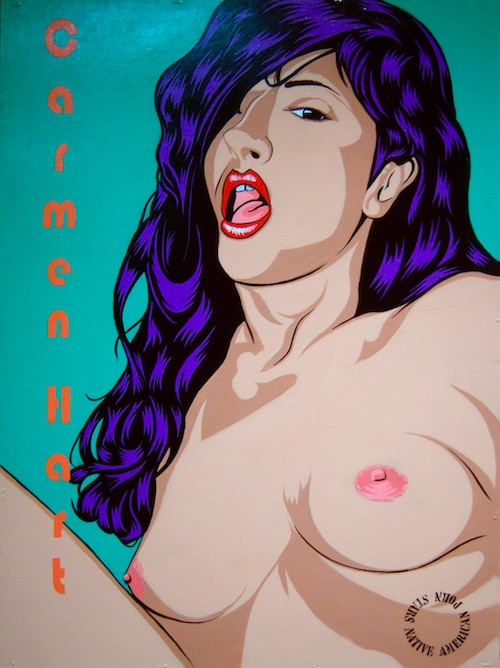

Carmen Hart 2 by Chris Pappan

Carmen Hart 2 by Chris Pappan

PB: You also don’t shy away from complexity in your thematic material. The Native American Porn Star series on your website could bring you accusations of reinforcing negative stereotypes, I imagine. But the other side of the coin, of those stereotypes, might be a bogus form of idealization by non-Natives. Or even, potentially, by American Natives themselves. Is that what you are up to? Defying all expectations? Or do you just like these women and want to celebrate them in a provocative way? Have these paintings been controversial within your community?

CP: What’s interesting about those pieces, and even in historical ledgers that I’ve researched, is that the subjects themselves are the ones who reinforce the stereotype.

PB: What does that mean?

CP: In terms of a contemporary context and with the uniqueness of the Native American experience there are those who want, but don’t know how, to connect with their heritage and can only express themselves in the ways they’ve been taught (by the “other”), therefore reinforcing a stereotype. Specific situations also factor in to this as well as in the case of the ledger art I was referencing where the artist had deliberately changed images of US soldiers getting shot by Natives to Natives shooting other Natives to make the artwork more appealing to buyers! The artist did this by adding long hair or literally sticking a feather in their hair.

In terms of the Porn Star series, my main intent for those pieces was to bring awareness that we are completely woven (assimilated?) into American society, even in “mainstream” pornography. The real danger of those works is people thinking I’m objectifying Native women, when there is so much violence directed towards women of color. That was certainly not my intent at all, and when working on these pieces, the models were very positive about what I was doing and (at least to me) projected a sense of strength. Another facet about those works I found interesting is that people in the Native community were asking me if they were real people! To which my answer was: of course, they are, why wouldn’t they be. I had also intended to include male figures into this series, but that involved a lot more research that I couldn’t devote more time to, but I did do a couple of paintings of Native World Wrestling Federation wrestlers to help balance that equation. And again, I feel strongly about how these works exemplify the complexity of the Native experience in popular American culture, and also our complexities as human beings.

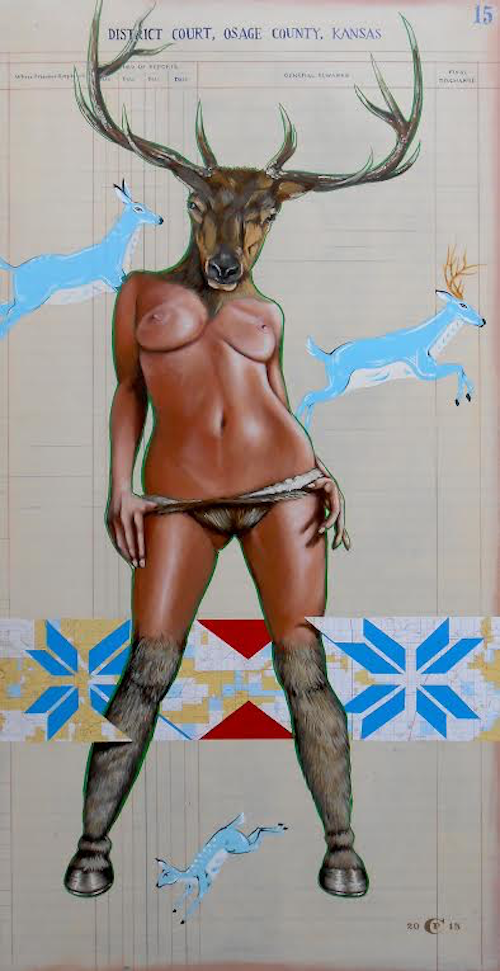

PB: On your website you also have fairly provocative paintings of naked (presumably) Native American women in high heels (in some cases) and with elk or antelope heads. I think that as a non-Native I am virtually helpless in understanding paintings such as “Bambi School Dropout” and “Antelope Woman Exposes Lie.”

Bambi School Dropout by Chris Pappan

Bambi School Dropout by Chris Pappan

CP: Those could be considered an extension of the porn star series I guess. The female figures with animal heads are referencing anthropomorphic deities within various mythologies, such as Buffalo Calf Woman from Lakota lore. But not only am I reinterpreting them visually based on my experiences (lowbrow, pop culture, etc.), but my intent is to also draw attention to the commonalities of human nature and creation stories across the globe. Bambi School Dropout references Deer Woman, a Southern Plains deity who is a sort of mischievous, malicious character who seduces men to their doom (like the sirens of Greek maritime legends). In the late 1800s to early 1900s there was a specific art training program at some of the Indian boarding schools in Oklahoma that was known as the Bacone school but was then later called Bambi school because of the many depictions of cartoon-looking deer (which I’m assuming was directly descended from ledger art). So, in my realistic, sultry depiction of Deer Woman (a taboo subject) I am breaking from tradition while simultaneously bringing awareness of it, with the title referring to myself as breaking from the tradition. Antelope Woman is from Acoma pueblo and is often compared to Persephone in Greek mythology and is known for her honesty and virtue. Therefore, her presence is meant to bring about awareness and create a better understanding among all of mankind.

PB: “Unrelenting” appears especially rich in symbolism. Would you please help us understand this painting?

CP: The main point of this painting is in direct response to people who “appropriate” elements of Native American culture for their own amusement, people who unexplainably don fake headdresses at concerts, or designs on clothing that are “native inspired.” These are direct micro-aggressions against us, and reinforces the idea that we have no propriety of our intellectual property. This painting depicts an anthropomorphic deity (deer or elk woman) convincing a young “hipster” the error of his ways, to remove his headdress. There are shields and spirits of ancestors dancing in the background as a protection and to give strength to our people to battle ignorance in a way that can be productive. Coyote is there to remind us of the absurdity of it all.

Unrelenting by Chris Pappan

Unrelenting by Chris Pappan

Peter Brown

Peter is an artist, writer, and translator. He has published two books of poetry in translation, including a French translation (with co-translators Caroline Talpe and Emmanuel Merle) of the poems of David Ferry, Qui est là? (La Rumeur Libre, 2018) and Elsewhere on Earth, (Guernica Editions, 2014), a collection by the French poet Emmanuel Merle. A collection of short stories, A Bright Soothing Noise (UNT Press, 2010), won the Katherine Anne Porter Prize.