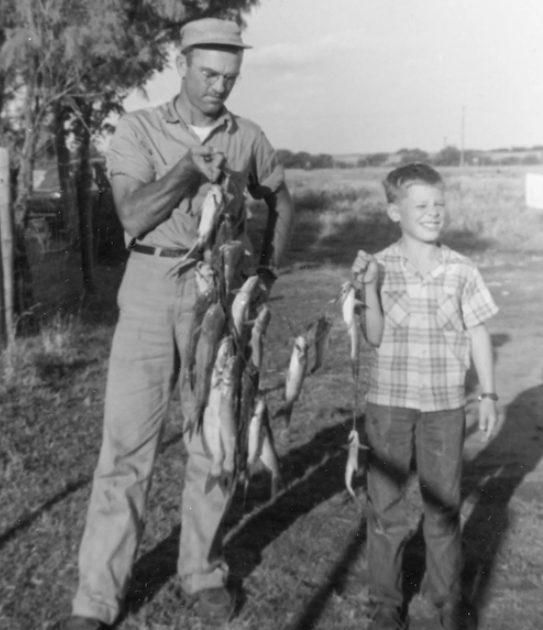

Photo courtesy of Evelyn Symes

The day Glenn left for Vietnam, our large extended family drove to the airport in a procession of five ancient Fords and Uncle Eben’s 1958 Cadillac. Mother filled the air in our car with empty admonitions to Glenn about laundry, diet, and writing home.

My brother and I, as always, sat in the back seat, me behind Mom and him behind Dad. At nine, I found the person boot camp returned to us in exchange for Glenn something of a marvel. This was a man with bulging muscles and a shorn head. I covertly admired him from across the expanse of cracked Naugahyde that separated us.

Once, when our eyes met, I saw the old Glenn looking back at me, and he was scared—really scared. Not like he was when Dad caught him sneaking out with Jason Green to meet Bonnie Paterson and her sister Nadine to go dancing. Not like that at all. We looked at each other for what seemed a long time. Then he shook his head in a can-you-believe-this? sort of way and looked back out the window.

By the time we arrived at the airport, Mother’s list of don’t-forgets had wavered to an end, leaving her digging in her purse to find a Kleenex.

With jets roaring overhead, our cars crept down every crooked row of old man Pederson’s makeshift parking lot before finally nosing into the far north fence. We stopped, and everyone was still, like we’d been frozen. Then Uncle Eben opened the door of his Cadillac and let the feeble refrigerated air condense on the car’s interior and evaporate into the undulating heat waves rising from the sticky asphalt.

Dad got out and opened the trunk for Glenn to get his gear. The uncles gathered around the back of the car with their hands stuffed in their pockets. Uncle Windy, the quiet one, reached in the trunk for the duffel bag, heaved it up on his shoulder, and began the long walk to the airport lobby. The rest of the uncles followed, passing my father and brother, who walked with slow, heavy steps. My mother and I walked behind them with the aunts, who offered Mother more Kleenex as tears gathered in their eyes.

About halfway across the parking lot, Glenn stopped and looked back. “Mom?” he called. She trotted up beside him and linked her arm through his. He kissed her cheek. She touched her forehead to his shoulder, straightened, and started walking again. I stayed behind. My Aunt Mae rested her hand on my shoulder like a blind woman, and I thought of the scripture, “and a little child shall lead them,” but I wasn’t sure Jesus meant into the airport lobby.

In fact, I wasn’t sure what was going on that day. But I knew it was important. Dad, who took no quarter as he raced, wrestled, and teased his only son, now held his arm around Glenn’s shoulders as tenderly as he did when he embraced our Great Aunt Lottie. When he leaned forward to look at Glenn’s face, I thought I would cry.

“Dad,” Glenn said, “Bobby Sutherland just got back from his tour. If they gave purple hearts for sunburn, he’d have a whole chest full.” This brought a thin laugh.

When we got to the door, the crush of travelers and the details of traveling compacted the last of our time with Glenn into a blur of insignificance that I will never forget.

The uncles extended a gauntlet of arms for final handshakes, which ended in a fierce embrace from my father and mother and a rough tousle of my hair delivered with a murmured, “Take care of Mac,” Glenn’s old arthritic boxer. Then my brother just strode through the gate and trotted to the plane with a back stiffened by love for his family and hope that love was really courage.

My Aunt Mae held my hand as we walked back across the parking lot while I cried. Mother walked without sight, with a calmness my aunts understood, but I resented. I don’t remember Dad.

After Glenn left, summer slowed to its usual crawl, making up for the speed it inflicted upon us during Glenn’s last visit. We began getting letters with strange names sprinkled through them: Nam Pen, Hue, La Drang. On thin, airmail tissue, Glenn told of a place so alien it may as well have been another planet with different stars in its night sky.

Then there was nothing.

The day the Army sent official notification of Glenn’s MIA status, my father’s strange animal cries haunted the night again. Through the day, he kept his anguish clamped between his teeth, circling the wheat fields on the Massey Ferguson, belching diesel fumes into the searing white heat of June.

But at night, his anguished voice called out for other young men dead in an older war I read about in school and had lived with since birth. Their names, the same names I remember rending the night air as a younger child, haunted Glenn and me as well as my father. As time passed, Dad called for them less and less until we thought they were finally buried. But now, they broke through the thin walls of his uneasy dreams of the past to the terrifying nightmare he feared his son now inhabited.

Mother canned green beans and made pickles, hung out our clothes, and took them in smelling of sun and fresh air. But her measured movements and careful words betrayed the delicate balance she labored to maintain. I pored over Glenn’s letters and marked the strange names on a National Geographic map.

By August, the swamp cooler could not make the nights bearable. I moved into the side yard to sleep on Dad’s old army cot. It stunk of mildew and age. Mother sponged it with Lysol and left it in the sun all morning before helping me carry my bedding to its narrow, taut surface. But the smell, as dank and stale as the breath of a newly opened grave, lingered and wafted into my dreams.

Mercifully, school started. Mr. Bell began science with a unit on astronomy. I asked him about the stars over Vietnam and showed him my map with the places marked from Glenn’s letters. He took me to the library while the rest of the class read, and I checked out a book with maps of the stars.

Miss Davis put the return card in the teachers’ section so I could keep it for as long as I wanted. At night, on my cot, I looked at the star maps with my flashlight, clicking it on and off as I tried to make sense of the night sky. I was careful to tuck the book under the covers before going to sleep but forgot once. The dew wrinkled the pages. Mother ironed them, but they never did lie flat after that.

Dad’s hoarse cries dredged up memories of past summer nights when Glenn and I slept in the side yard, Mac snoring on the ground between us, with Glenn’s strong fingers holding my hand, silently reassuring me that Dad was okay. As the memories flitted around my brain, I searched the night sky for Orion’s belt and hoped Glenn could see it too.

Evelyn Fletcher Symes

With a Masters in English Creative Writing, Evelyn carries on her large extended family's long tradition of storytelling. Her war stories give voice to her seven uncles who served and came back only to realize the conflicts fought on the battlefields did not end on the dates found in history books—they continued to create casualties in their lives and in the lives of those who loved them. Evelyn writes under the gray, misty skies of Washington state, coming out only long enough to tend her small orchard and can applesauce each fall. You can find more of her stories in Pure Slush, The Opiate, Everyday Fiction, and other literary journals.