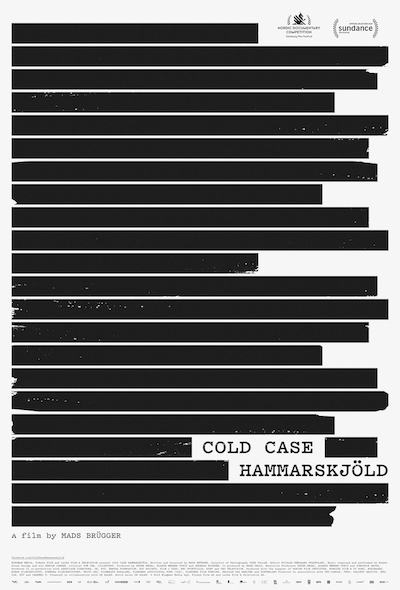

Cold Case Hammarskjöld

Director: Mads Brügger

Released: Aug. 16, 2019 (United States)

It’s hard not to have noticed that documentary film—a genre once reviled for its standard fare of eat-your-vegetables instructional films—is enjoying a creative and commercial renaissance. All over the world, visionary documentary filmmakers are pushing the boundaries of the form, employing a dazzling array of storytelling techniques to rival anything in narrative film, and often going far beyond that. But by any standard, even in the midst of this boom, one of the boldest and most original documentary features in recent memory is Cold Case Hammarskjöld (2019), directed by the Danish journalist turned filmmaker Mads Brügger.

On its face, the film is an exploration of the 1961 plane crash that killed Dag Hammarskjöld, the UN Secretary General, as he tried to negotiate a cease fire between the forces of the newly independent Republic of the Congo and secessionists backed by Western mercenaries and the country’s former imperial ruler, Belgium. The circumstances of Hammarskjöld’s death were certainly suspicious at a moment when powerful parties undeniably had an interest in undermining his efforts, particularly European mining concerns and others invested in maintaining white colonialism. Hammarskjöld’s plane, a DC-6, had been left unattended for some hours the night before takeoff. According to some accounts, a bomb planted onboard failed to explode, triggering Plan B, the dispatch of a mercenary Belgian fighter pilot known as “the Lone Ranger” who shot it down. Hammarskjöld was the only passenger whose body was not burned to a crisp; a photo of his corpse plainly shows an ace of spades tucked into his shirt collar, a notorious calling card of the CIA. A UN investigation conducted at the time declined to come to a conclusion, leaving doubt swirling around the case ever since.

Yet for a film that attacks such a grim topic, Cold Case Hammarskjöld is startlingly playful and comic, even if its humor is as dark as can be—which is Brugger’s trademark approach. The director plunges into the story with brio: one white Scandinavian venturing into Africa in search of the truth about another. Together with Göran Björkdahl, a bureaucrat in the Swedish foreign service, he travels around Africa and Europe following leads and interviewing a cast of shady characters in droll scenes where the humor is usually at his own expense. Brügger films their preparations for their foray to the crash site, including a survey of their equipment, which includes two pith helmets, and the cigars he and Björkdahl will smoke when they solve the mystery. The film frequently returns to interstitial shots of Brügger playing solitaire with a deck consisting only of aces of spades. The narration is knowing and arch, even as it deftly maintains a sinister mood, and offers a sly commentary on the history of white colonialism. Brügger even deadpans that from the start, the inquiry into Hammarskjöld’s death was just an excuse to travel around Africa, hang out with Belgian mercenaries, and do lengthy interviews “with elderly, liver-spotted white men.”

As the two men go deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole, the story spirals out in fiction-beggaring ways. But when they ultimately fail to find definitive proof of foul play, Brügger turns despondent. It is here that he confesses that he has turned to what he calls the “tricks of his trade” to save his “shipwrecked film.” And tricky they are: the director dresses in the ivory-colored safari suit of the villainous main character—a South African white supremacist—as he dictates voiceover to not one but two different Black women who serve as stenographers, and challenge him over some of the documentary’s plot points. He freely admits that even he doesn’t understand the meaning of this device, the film’s most outré conceit, or why he chose two secretaries instead of one. (I was relieved by this confession, because I felt sheepish that I couldn’t coherently explain a choice that seemed freighted with meaning.) But it’s the kind of device that gives the film its frisson, and as good an example as I can recall of Sontag’s argument for the prominence of style over substance in a work of art. Intentionally or not, Brügger seems to be proving the premise of his countryman Lars Von Trier in his 2003 documentary The Five Obstructions: that creativity requires—and even thrives on—restrictions and limitations.

At one point, as the director describes how his investigation has came up empty, one of the

secretaries asks:

“Is that why this became fiction?”

“It’s not—it’s a documentary,” Brügger insists.

“OK,” she says, nonchalantly.

This is a film that seeks to separate truth from fiction, even as the filmmaker knows that he himself is blurring the line, at a time when the contemporary audience has come to understand that even “non-fiction” stories are as constructed and subjective as their narrative cousins.

But the Hammarskjöld story soon becomes only the portal to an even bigger and weirder mystery, as Brügger and Björkdahl stumble upon a shadowy, now-defunct organization called the South African Institute for Maritime Research (SAIMR), a paramilitary unit of the apartheid regime that engaged in covert operations and other dirty tricks to destabilize Pretoria’s majority Black neighbors. Allegedly it was SAIMR that carried out Hammarskjöld’s murder, but that was the least of it. According to a remarkably forthcoming but very believable former SAIMR officer, the organization also operated secret labs deep in the sub-Saharan jungle in a genocidal attempt to weaponize the HIV virus in hopes of killing Black Africans en masse.

Keith Maxwell, SAIMR’s central villain, is a character out of a Bond novel. Known to his men as “the Commodore,” Maxwell habitually dressed entirely in white—which Brügger mimics—except when he appeared in the uniform of an 18th century Royal Navy admiral, à la Lord Nelson. He also purported to be a medical doctor, which he wasn’t, as he established clinics in poor regions of Africa that injected patients with HIV under the guise of vaccinations against it. (Brügger stops short of another oft-rumored conspiracy theory, that HIV and AIDS were actively created as bioweapons by nefarious governmental forces.)

When Cold Case was released in 2019, the allegation about weaponizing AIDS was met with deep skepticism. Watching it again recently, the truth was no more clearcut, but I was struck by how much more explosively that claim reads today. The United States is already gripped by a wave of anti-vax fanaticism in the fight against the novel coronavirus. At the mildest end of this resistance is the unfounded contention that the COVID-19 vaccine was insufficiently vetted. At the more extreme edge is the claim that COVID is itself a hoax, as a weapon of authoritarian control . . . or if it is real, was deliberately created in a lab (perhaps by the Chinese, perhaps by the CIA, perhaps by Anthony Fauci in the Washington Nationals’ dugout), and the vaccine a Trojan horse designed not to inoculate its recipients but to infect them.

In that climate, hearing compelling testimony that the South African military did the same thing with AIDS is not good news for the forces of science, medicine, and reason itself, which are trying to beat back an army of Know Nothing anti-vaxxers. From the Nazi concentration camps, to the Tuskegee experiment, to the collusion of Soviet psychiatrists in the Stalinist police state, wariness about the goodwill of the medical community is not totally unfounded. What is ironic and bizarre, however, is how that wariness has now been transformed into a cudgel of autocracy and white supremacy itself, when it was largely those very forces that were responsible for the crimes that gave rise to skepticism in the first place. Even as apartheid-era South Africa might have actively been trying to murder Black people with vaccines, the Trump administration was, by some accounts, happy to let the pandemic rampage through communities of color. Of course, all these allegations about SAIMR, Maxwell, and this plot remain conjecture. A card at the end of the film notes how hard it would be to weaponize the HIV virus, and the absence of any evidence that it was ever accomplished. But that doesn’t mean that Pretoria—not a regime known for the moral high ground—didn’t try.

For such an innovative, mischievous film (about such a grim and horrifying topic), Brügger ends Cold Case with a surprisingly earnest note about how different Africa might be today if Dag Hammarskjöld had lived to fulfill his vision, a blunt indictment of the rapacious forces of colonialism and capitalism that have kept their collective foot on the neck of the people of the African continent, and of people the world over. Just two years after its release, the film is well worth revisiting in our radically new political—and epidemiological—climate. Even at a time when documentary is flourishing with visionary filmmakers pushing the boundaries of the form, Mads Brügger is pushing them further than almost anyone else. It is our good fortune that he is doing so with topics that resonate in profound ways, and with style to match.

Robert Edwards

Robert is a writer and filmmaker. His films include Land of the Blind starring Ralph Fiennes and Donald Sutherland, and When I Live My Life Over Again (aka One More Time) starring Christopher Walken and Amber Heard, and the documentaries Sumo East and West and The Last Laugh, with Ferne Pearlstein. He was an infantry and intelligence officer in the US Army, and was a captain in the 82nd Airborne Division in Iraq during the Gulf War.