It was a legal lynching which smears with blood a whole nation. By killing the Rosenbergs, you have quite simply tried to halt the progress of science by human sacrifice. Magic, witch-hunts, autos-da-fé, sacrifices—we are here getting to the point: your country is sick with fear . . . you are afraid of the shadow of your own bomb.

—Jean-Paul Sartre (1953)

Sunday, June 14, 1953

“Michael, I don’t want to go.”

This proclamation was delivered in a high-pitched whine that pierced Michael’s ears and raised the hair on the back of his neck. Robert was perfectly agreeable for a six-year-old but prone to tantrums when under duress, and the poor boy had experienced nothing but duress for a solid three years.

Michael sighed more heavily than a ten-year-old should ever have to sigh and sat down next to his brother on the bed.

“It’ll be okay. There will be a lot to see. And Mr. and Mrs. Bach want us to go.”

“Because it will help Mommy and Daddy?”

“Yup,” Michael confirmed.

Robert lapsed into thoughtful silence while Michael tied his shoes. The bus was leaving soon, and if there was one thing to be said about Mrs. Ethel Rosenberg’s good Jewish firstborn son, it was punctuality.

“Boys!” called Mrs. Bach from downstairs. “It’s time to go!”

Michael took Robert’s hand—something he had taken to doing far more often over the last three years, despite the two growing older with each passing day—and descended the stairs toward Ben and Sonia Bach.

“Do you have the letter?” asked Sonia, and Michael nodded, patting the pocket of his coat.

The boys’ time in New Jersey with the couple had been as pleasant as possible, and certainly better than the Hebrew Children’s Home. But Michael still ached for New York; he ached for the seven years of childhood he had enjoyed before everything changed.

“Washington D.C., here we come!” exclaimed Ben.

The drive to Philadelphia was charged with electricity. Ben and Sonia did most of the talking—near-manic plans for the demonstration, frenzied conjecture about the Supreme Court’s ruling on the execution stays—while Robert stared forlornly out the window and Michael wondered what his parents were doing.

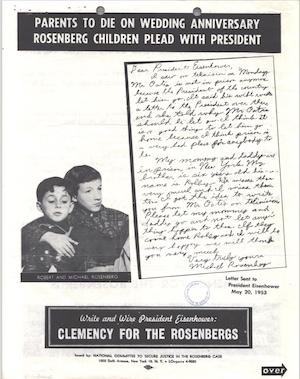

The foursome boarded their second bus to the Capitol and drove south. The event was expected to draw almost ten thousand protestors, and surely that would have to convince President Eisenhower to reconsider. Michael fingered the paper in his pocket that was covered with his own childish handwriting, filled with big words like “espionage” and “clemency.” Even at ten, he realized it was his parents’ last chance; even at ten, he knew what the Supreme Court decision would mean.

“We’re almost there, boys,” spoke Mrs. Bach, adjusting her hat and buttoning Robert’s jacket. “Remember to stay close.”

It took only half an hour before the crowd and white noise of thousands of voices aggravated Robert to tears. Through a whirlwind of posters and chanting and adult legs, the brothers were swept along the streets of the Capitol, bit players among thousands of other souls, all demanding freedom for the immigrant Jewish couple from New York City who would rather die than add one more name to McCarthy’s blacklist. Sonia thrust a sign into Michael’s hand: “Please don’t kill my Mommy and Daddy” scrawled in bold, black letters. He clutched the handle, grateful to have something to hold on to.

“What’s happening?” asked Robert repeatedly, but Michael himself wasn’t quite sure.

By the end of the day, however, the boys had learned very little they didn’t already know. By the end of the day, they had walked for miles, stood for hours. By the end of the day, they had hand-delivered the letter in Michael’s pocket to the White House itself, the letter penned in Michael’s shaky penmanship under the direction of the Bachs, the letter borne from a young boy’s longing and grief. It was a plea for President Eisenhower to stop the execution of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg—the only parents the brothers had ever known—because who can ignore the pleading of children?

The Secret Service could, it turned out, and the Bachs and the Rosenberg boys were denied entry to the White House by a uniformed man at the guard station like the gatekeeper to Oz.

“Please give this to President Eisenhower,” requested Michael, having rehearsed with Mrs. Bach the previous day. The guard, face like a mask and eyes never quite meeting those of the child before him, accepted the slightly crumpled paper stoically and without comment.

Michael never did find out if President Eisenhower read the letter.

Monday, June 15, 1953

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, convicted for conspiring to violate the Espionage Act of 1917 . . .

. . . sentencing them to death on April 5, Judge Irving Kaufman maintained, “I believe your conduct in putting into the hands of the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted Russia would perfect the bomb has already caused, in my opinion, the Communist aggression in Korea.” [1]

“Did you read what the Pope said? The Pope! Listen to this: ‘When two children, Michael and Robert, are involved in this tearful fate, many hearts can be melted, before two little innocents on whose soul and destiny the death of their parents would forever leave sinister scars.’”

President Eisenhower echoing the sentiment, “. . . a crime worse than murder.”

“How does the Pope know our names? Did you hear that, Michael?!”

. . . Julius Rosenberg quoting in response, “There had to be a Rosenberg case because there had to be an intensification of the hysteria in America to make the Korean War acceptable to the American people.”

“And Picasso? Just read this! He said, ‘The hours count. The minutes count. Do not let this crime against humanity take place.’”

An application for stay of execution was filed herein on June 12, 1953 . . .

“Shhhh! Here it is! Robert, quiet down, we need to hear!”

Court denied a motion for leave to file an original petition for a writ of habeas corpus and for a stay, and then adjourned.

“Wait, is that it? What does it mean?”

“They denied the stay of execution,” said Ben wearily. “By a vote of five to four.”

. . . scheduled for June 18, pending an intervention by . . .

“But . . . when? When will it be?” Sonia’s voice was a whisper.

“Thursday.” Ben rubbed his eyes. “Thursday.”

. . . best be summed up in the words of Justice Kaufman: “Indeed the defendants Julius and Ethel Rosenberg placed their devotion to their cause above their own personal safety and were conscious that they were sacrificing their own children, should their misdeeds be detected—all of which did not deter them from pursuing their course . . .” [2]

“What’s happening?” Robert asked. But in the resounding silence, it was too loud to hear anything at all.

Tuesday, June 16, 1953

“Are we there yet?” asked Robert meekly.

“Almost,” assured Manny from behind the wheel.

The day had started uncomprehendingly early, with Ben driving the boys to Manhattan to meet Manny Bloch, their parents’ long-time attorney. The brothers had been driving north ever since, the morning sun streaming through the windows and heating the car’s interior to near-uncomfortable levels.

“Why is it called Sing Sing?” Robert continued.

“It was the name of the town before Ossining,” said Manny absentmindedly. “I think it comes from some foreign phrase. It means ‘stone on stone.’”

A vision bloomed behind Michael’s eyes, stones stacked on top of stones stacked on top of stones, stones formed into rudimentary cubes, cubes stacked on top of cubes stacked on top of cubes. There were people entombed inside, inside all that stone, and they could not break free; they were wailing in agony and fear inside those barren cells.

His parents were in those cells.

The process of checking in with prison security was tedious but unremarkable; the lawyer spoke to the guards at length. Michael and Robert trailed after the adults like ducklings, traversing the winding hallways of the prison wing and passing endless identical doors along the way. The children were sheltered from any sight of the degenerates and Communists deemed “criminal” by the judicial branch of the United States of America—terrified as it was of the Soviets—and it was not until the guard opened the door of the attorney conference room that they spotted any other human beings at all.

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg sat at opposite ends of the council table. Three years’ worth of tumult, trials, and terror showed on their faces, and they were both too thin; but they simultaneously looked exactly as Michael always expected them to look, and relief bubbled in his chest like magma.

“Mommy!” yelled Robert, sprinting into the room, throwing his arms around Ethel like a vise. Michael followed, hugging first his mother and then his father, pacing the length of the council table, unable to sit still. Manny shook Julius’s hand and gave Ethel a peck on the cheek, then immediately launched into a description of complicated legal tactics.

“There’s still an eleventh-hour appeal for clemency. Or Justice Douglas could stay, based on the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 . . .”

The adults’ strategizing drifted over Michael and Robert’s heads as they circled the table to hug their mother and father, again and again and again, with Manny responsible for the bulk of the conversation, his words forceful and delivered in rapid-fire succession.

Eventually, the lawyer wound down and busied himself organizing a sheaf of paper in his briefcase. Michael and Julius played Hangman on a legal pad; Robert sat limply in Ethel’s lap.

There was a perfunctory knock at the door before a guard barged in.

“Time’s up,” he announced, addressing Manny alone and ignoring the children completely.

Ethel stood and transferred Robert to the floor. She reached out to hug Michael, then stepped back and clasped her husband’s hand.

“Come on, boys,” Manny ordered, briefcase in hand and legal code dancing behind his eyes. Robert obediently joined the lawyer by the door, looking back over his shoulder at Ethel, while Michael remained rooted in place. He felt the unbearable weight of grief—which, at ten, was mostly foreign to him—and something shattered deep in his chest.

“One more day to live!” cried Michael, unable to dam the words behind his lips. He clung to the jacket of Julius’s suit as Manny attempted to cajole him into the hallway. Finally resorting to bodily removing the boy, Manny strode down the hall, clutching a child with either hand, hell-bent on the exit. Ethel and Julius remained motionless in the conference room, staring helplessly at their retreating children. Michael’s wails echoed through the hall long after he turned the corner and did not cease until the three emerged back into the sunlight outside.

“Only one more day to live!”

Wednesday, June 17, 1953

“St. James Place,” Michael read off the card. “Rent, fourteen dollars.”

Robert carefully counted out four single dollar bills, biting his lip in concentration.

The game had become a ritual, an afternoon source of comfort, and the brothers were each turning rather savvy in the ways of real-estate law, given the circumstances.

Michael was going straight to jail—not passing Go, not collecting $200—when an excited shout behind him caused him to jump in his chair.

“The Douglas stay! The Douglas stay!”

Sonia burst into the kitchen, throwing her arms up in victory.

Ben came rushing in from the living room, eyes huge, smile wide.

“He stayed it?!”

“I think so. I heard something in the car on the radio! Boys, one of you, turn on the television, quickly!”

Robert jumped to his feet, delighted to be in the presence of an emotion other than heartache for the first time in a long while. Michael ran behind him, joy filling his molars and his kneecaps and the tips of his fingers. The Bachs followed the children, staring at the television as the picture warmed into view, clutching hands, too excited to sit down or stand still.

Every channel featured a newscaster telling the tale of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg—martyrs for freedom or martyrs for the Soviets, depending upon the political bent of the viewer—and the thin thread upon which they were walking between life and death.

The Bachs yelled with glee while Robert raced around the room, clapping his hands and shouting in a singsong. The children washed their hands and ate lunch; they finished the game of Monopoly. The radio in the kitchen voiced a constant stream of predictions regarding the potential fate of the Rosenbergs like an analog soothsayer. Michael basked in the sheer happiness filling the house like hydrogen gas from corner to corner, far too young to remember what hydrogen gas ended up doing to the Hindenburg.

For eight hours, it was the best day. For eight hours, it felt like victory.

#

The Court is now convened in Special Term to consider an application by the Attorney General to review the stay of execution of Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg, petitioners, v. Wilford L. Denno, Warden of Sing Sing Prison, June 1953 Special Term, denying a stay . . .

“What’s the matter?” asked Robert of the room at large, sensing the shift in the mood like animals sense a shift in the wind.

Ben slammed his fist against the table, then covered his eyes and exhaled deeply, then slammed his fist against the table again.

“The FBI doesn’t want Ethel,” Mrs. Bach offered quietly. “They just want to make Julius talk.”

“Damn Hoover!” snarled Ben. “Damn him to hell!”

Robert startled visibly, then drew next to Michael and buried his face in his brother’s side.

“Why don’t you boys go play outside,” said Sonia, laying a calming hand upon her husband’s shoulder, where it rose and fell in time with his ragged breathing.

“Why?” asked Robert, but the woman merely tied the child’s shoes with stiff fingers and led both boys to the entryway. Robert bounded into the yard, but Michael hung back, trying to meet Sonia’s eyes, desperate for the comfort he once felt in his certainty that adults could fix anything and everything.

“Tomorrow is their anniversary,” said Michael, nearly inaudibly. “Tomorrow is when they got married. A long time ago, when they were young.”

Sonia avoided Michael’s gaze but gathered the boy into a rough hug, staring off into the distance.

“Your parents love you so much, Michael,” she finally managed. “Your mother loves you.”

Michael clutched her back, three years bereft from maternal attention, but Sonia eventually released him and stepped away.

“Stay with your brother,” she instructed, and retreated back into the house.

“They’re using her as a pawn!” Michael heard Ben growl as the door closed behind her. “Julius will never name anyone.”

Michael trudged into the yard and joined Robert in the grass, where the boy was glumly rolling an old rubber ball back and forth at his feet.

“Michael, are Mommy and Daddy going to die again?” questioned Robert, and Michael found that he had no words at all.

Thursday, June 18, 1953

Dearest Sweethearts, my most precious children . . . [3]

ROSENBERGS MUST DIE, HIGH COURT, IKE RULE – Cleveland News

Only this morning it looked like we might be together again after all. Now that this cannot be, I want so much for you to know all that I have come to know. [4]

POLAND OFFERS TO TAKE ROSENBERGS IF REPRIEVED – Northern Whig, Northern Ireland

Always remember that we were innocent and could not wrong our conscience. [5]

CONVICTED SPIES REFUSE TO TALK – San Antonio Express-News

Eventually, too you must come to believe that life is worth the living. Be comforted that even now, with the end of ours slowly approaching, that we know this with a conviction that defeats the executioner! [6]

ROSENBERGS STILL WAITING – Dundee Courier, Scotland

You will not grieve alone. That is our consolation and it must eventually be yours. [7]

Your lives must teach you, too, that good cannot flourish in the midst of evil; that freedom and all the things that go to make up a truly satisfying and worthwhile life, must sometime be purchased very dearly. [8]

ROSENBERGS AWAIT FINAL DECISION – Belfast Telegraph, Northern Ireland

We wish we might have had the tremendous joy and gratification of living our lives out with you. Your Daddy who is with me in the last momentous hours, sends his heart and all the love that is in it for his dearest boys. [9]

ROSENBERGS TO DIE FOR ATOM SPYING – Cincinnati Enquirer

SPIES GET ONE MORE DAY – New York Daily News

We press you close and kiss you with all our strength. Lovingly, Daddy and Mommy [10]

VIGIL STARTS FOR ROSENBERGS – Shields Daily News

Friday, June 19, 1953

Prayers in Hebrew wafted out on the breeze, choreographed to the song of the setting sun. Michael heard the words as if from a great distance—familiar words, intimate ones, an immediately recognizable cadence that brought to mind candlelight and brisket and the inarguable presence of God—even though the voices were only coming from the open windows of the house next door.

Baruch Atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech ha’olam asher kidshanu b’mitzvotav vitzivanu l’hadlik ner shel Shabbat.

The Douglas stay had been canceled early that morning. The execution had been scheduled for 11 p.m.

Blessed are You, Infinite One, who makes us holy through our actions and honors us with the light of Shabbat.

“It’s Shabbat,” argued the defense. “Religious liberty,” suggested the defense. “Appeal,” demanded the defense.

Barukh ata Adonai Eloheinu, melekh ha’olam, asher kideshanu be’mitzvotav ve’ratza banu, ve’shabbat kodsho be’ahava u’ve’ratzon hinchilanu, zikaron le’ma’ase vereshit.

“Our liberty is maintained only so long as justice is secure,” [11] responded Justice Clark. “To permit our judicial processes to be used to obstruct the course of justice destroys our freedom,” [12] preached Justice Clark.” “Though the penalty is great and our responsibility heavy, our duty is clear,” [13] determined Justice Clark.

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, Who sanctified us with His commandments, and hoped for us, and with love and intent invested us with His sacred Sabbath, as a memorial to the deed of Creation.

The execution was rescheduled for 8 p.m. It would be before sunset; it would be before Shabbat. It would be entirely up to the President, it all turned out, and then it would be over, one way or the other.

Baruch atah, Adonai Eloheinu, Melech haolam, borei p’ri hagafen.

Michael sat cross-legged on the carpet, glued to the television, his bottom numb from immobility. For hours, updates had been popping up on the screen without warning, a visual representation of the machinations of a government that would determine if Michael’s parents could attend his college graduation.

Praise to You, Adonai our God, Sovereign of the universe, Creator of the fruit of the vine.

The picture hiccoughed suddenly as the news was interrupted by yet another bulletin, the bulletin, bright letters of text filling the screen like a warning.

EISENHOWER REFUSES PLEA FOR EXECUTIVE CLEMENCY

“What does it say?” Robert inquired, and was quickly shushed by the adults.

By immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war, the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people . . . whose deaths may be directly attributable to what these spies have done. [14]

Somewhere in the world, the Mourners Kaddish blossomed from a whisper, ascending from nothingness until it filled every corner of every room, until it was taken up by a chorus of other voices in many languages, accents, and tones.

Yitgadal v’yitkadash sh’mei raba b’alma di v’ra chir’utei; v’yamlich malchutei b’hayeichon u-v’yomeichon, uv’hayei d’chol beit yisrael, ba-agala u-vi-z’man kariv, v’imru amen.

“That’s it,” Michael moaned, tears streaming down his face, his fingernails biting into the soft flesh of his palms. “Goodbye.”

Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name throughout the world which He has created according to His will. May He establish His kingdom in your lifetime and during your days, and within the life of the entire House of Israel, speedily and soon; and say, Amen.

On the television, still frames of police mug shots and Ethel and Julius embracing and the hammer and sickle flashed by rapid-fire. The live camera switched to an extreme long take, panning over the mass of people in the street—men and women, Jews and Gentiles, Americans and foreigners alike. Demanding clemency for the Rosenbergs, all were united in their protest of injustice; all were holding burning candles aloft.

Y’hei sh’mei raba m’varach l’alam u-l’almei almaya.Yitbarach v’yishtabah, v’yitpa’ar v’yitromam, v’yitnasei v’yit-hadar, v’yit’aleh v’yit’halal sh’mei d’kudsha, b’rich hu, l’ela min kol birchata v’shirata, tushb’hata v’nehemata, da-amiran b’alma, v’imru amen.

“The vigil is in New York and Paris and Washington D.C.,” the newscaster reported. “The Communists,” he reminded the globe, “are swarming in Europe tonight.”

May His great name be blessed forever and to all eternity. Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored, adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He, beyond all the blessings and hymns, praises and consolations that are ever spoken in the world; and say, Amen.

“Phone lines,” reported the newscaster, “will remain open at Sing Sing Prison until 8 p.m.” Pausing for effect, basking in the mounting tension, he regarded the television audience gravely. “If the Rosenbergs reconsider their refusal to plead guilty, the President is ready until the last possible moment to spare their lives.”

Y’hei sh’lama raba min sh’maya, v’hayim, aleinu v’al koi yisrael, v’imru amen.

The boys were sent outside to play.

May there be abundant peace from heaven, and life, for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

“What’s happening?” Robert repeated, a baseball bat dangling limply from his hand. “Michael?”

Oseh shalom bi-m’romav, hu ya’aseh shalom aleinu v’al kol yisrael, v’imru amen.

Now, as his neighbors prayed over Shabbat dinner and the sound of Hebrew stirred an ache in his chest, Michael turned his face toward the sun. The day was slowly starting to slip below the horizon; New Jersey was awash in streaks of pink and yellow. Night loomed on the other side of the sunset, muggy and lonesome, and Michael was suddenly struck by a distaste for the dark he had never before experienced.

“Come on,” he said brusquely to Robert, grabbing the bat from his brother’s hand. “It’s you and me. You pitch and I’ll hit.”

He who creates peace in His celestial heights, may He create peace for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

THE END *

* “This court has never affirmed the fairness of the trial. Without that . . . there may always be questions as to whether these executions were legally and rightfully carried out.”

—Justice Hugo Black, Rosenberg v United States, 346 U.S. 273 (1953).

[1] United States of America vs. Julius Rosenberg et al, 195 F.2d 583 (2d Cir. 1952).

[2] United States of America vs. Julius Rosenberg et al, 195 F.2d 583 (2d Cir. 1952).

[3] Rosenberg, Julius and Ethel. “Julius and Ethel Rosenberg Letter to Michael and Robert Rosenberg.” Personal Record. Collection, Michael and Robert Meeropol. June 18, 1953, accessed 10 October 2014.

[4] Rosenberg, Julius and Ethel. “Julius and Ethel Rosenberg Letter to Michael and Robert Rosenberg.” Personal Record. Collection, Michael and Robert Meeropol. June 18, 1953, accessed 10 October 2014.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Rosenberg, Julius and Ethel. “Julius and Ethel Rosenberg Letter to Michael and Robert Rosenberg.” Personal Record. Collection, Michael and Robert Meeropol. June 18, 1953, accessed 10 October 2014.

[9] bid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Rosenberg v United States, 346 U.S. 273 (1953)

[12] Ibid.

[13] Rosenberg v United States, 346 U.S. 273 (1953)

[14] Eisenhower, President Dwight D. “Statement by the President Declining to Intervene on Behalf of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.” 19 June 1953.

Shannon Frost Greenstein

Shannon Frost Greenstein (she/her) resides in Philadelphia with her children and soulmate. She is the author of These Are a Few of My Least Favorite Things, a full-length book of poetry available from Really Serious Literature, and Pray for Us Sinners, a short story collection with Alien Buddha Press. Shannon is a former PhD candidate in Continental Philosophy and a multi-time Pushcart Prize nominee. Her work has appeared in McSweeney's Internet Tendency, Pithead Chapel, Litro Mag, Bending Genres, Parentheses Journal, and elsewhere. Follow Shannon at shannonfrostgreenstein.com or on Twitter at @ShannonFrostGre.