Yury Lvovich during the war (1941-46)

“ . . . But there is another victim: my son, a Komsomol member, who fought in the war as an artillery officer and was among the first to take Berlin. His war decorations and awards, earned with courage and blood, defending the beloved Soviet homeland, are stained by the shame of his father. He is ‘the son of an enemy of the people’ . . .”

—From a petition for amnesty addressed to the Soviet Minister of Internal Affairs by Yakov Danilovich Lvovich, 1953 [1]

The Boombox

“Honestly, it is the Russians who won the war!” says Frank. This is the first time I hear this in America, the affirmation of a muted, semi-obscured, and unpopular version of Transatlantic history and the acknowledgment of Russian sacrifice, of the unspeakable horrors and suffering of the country which lost twenty-seven million people in the war. The victory of the Allies in World War II, presented to the American public in the form of the triumphant D-Day, with gorgeous views of the grand Omaha Beach and symmetrically-lined white crosses of the American Cemetery in Normandy, was a one-sided “happy ending,” a uniquely Western, Anglo-American achievement, even if Ken Burn’s PBS documentary on World War II offered some honest-yet-downplayed dispatches from the Eastern front.

My friends Rebecca and Frank’s country house in Plainfield, Massachusetts, has the feel of a Russian dacha. Like in Russia, furniture and objects from the city appear to have their second life here, in retirement and close to nature, where things are simpler and cheaper: dry brittle wicker chairs with faded cushions, a large dinner table, and grandchildren’s toys in the corners and under the chairs. Dahlias of primary colors, crimson and yellow, are cut from the backyard garden, and one’s eyes rest on the breathtaking view of the Berkshire Highlands outside the glass terrace. In the backyard, next to a tiny garden, a bright red firetruck from the 1970s, discharged from Plainfield’s municipality and acquired by Frank, is parked incongruously, with the weed pushing wildly around its wheels, in the otherwise smoothly mowed lawn. Having lost its function, the truck looks like a piece of surrealist art, one of Marcel Duchamp’s “objets trouvés” or Christo’s “modified space.”

It is perhaps because Rebecca and Frank’s dacha in Massachusetts offers an opportunity for a second life of objects that I found there a dinosaur cassette recorder, a boombox from the 1980s, formerly belonging to their son, saved from total extinction during the sweeping move to all things digital and “nebulous.”

But the truth be told, it is not the digital revolution that stopped me from finding a cassette player to listen to the interviews with my father that I had recorded twenty-five years ago. I couldn’t bring myself to hold those cassettes in my hands, let alone hear my father’s voice for all this time in America, busy as I was launching an academic career, raising a daughter, getting divorced and raising another daughter, conceived the year my Dad died, as if I hoped for reincarnation.

My Dad was the first family death I experienced, and I was frightened, not only devastated, by it. During his last moments, when he was semi-conscious, gasping for air under morphine, I did not find the courage to hold his hand and stood in the hallway—until I was told to come in—when it was over. I silently grieved and was subdued by his death; then, one day, months later, I surprised myself by not being able to contain a torrent of tears at the funeral of our department chair, whom I perceived as a father figure during the first years of immigration and professional remaking. It was in the austere and foreign environment of an Episcopal church in Montclair, New Jersey, full of strangers, that my guards had unexpectedly dropped, and a cork burst open, letting rivers of pain flow.

I taped the interviews during a brief remission before my Dad spiraled to the final turn of his illness. On the tape, one hears in the background the cacophony of hospital sounds: doctors paged through the loud-speakers, lunch trays clunking, patients shuffling their feet, dragging along IV stands, toilets flushing, lots of coughing, and the old-fashioned phone ringing that for some reason seems especially intrusive. I wanted him to talk about his family, his brother who had died young, his father who had spent most of his life in gulags, and about his mother, my grandmother Yulia, who had followed her husband to Siberia, like a proverbial Decembrist wife. [2] But the fact of the matter was the war was the only thing he wanted to talk about. From any question I asked on any topic, he slipped to the subject of war, which defined his identity and his life, his past and his present, and was passed on to the next generation—to me—in an indirect but equally traumatic form.

The paradox was that war gave his life meaning and brought about the justice that he longed for: he defended his Motherland, even if his Motherland was not protective of him, a Jew who lived in a society with structural anti-Semitism and suffered oppression and discrimination. And as if it were not enough, he was the “son of an enemy of the people,” [3] a stigma stamped on his forehead, although he did his best to conceal it every step of the way, but his own fear to be discovered made him an untrustworthy person who inherited his father’s “crimes.” He felt that this stigma could only be erased—and his dignity restored—by proving his loyalty with his blood while fighting “Za Rodinu! Za Stalina!” [4]

He enlisted for the front at age seventeen, claiming that in battle people are truly equal and nobody is different (Jewish) or a son of a traitor. Fighting the war on Katyushas, [5] the legendary weapons associated with Soviet victory, intensified his pride and his sense of community, camaraderie, loyalty, and human connections, crystallized by everyday exposure to mortal danger. But have the medals and published words fulfilled his self-exoneration? Have they alleviated the awkward double genitive case of “the son of an enemy of the people?”

World War II is an international term, but in Russia the war is called Velikaya Otechestvennaya Voyna (The Great Patriotic War), since it took place on its own territory, in people’s towns and homes. Referred to as “the war” the one and only, it is omnipresent in the country’s cultural texture even seventy-five years later: in every family, in schools, in the media, in songs and literature, in street names, monuments, and on TV. The war was perhaps the only matter in Russia where Soviet ideology and personal issues merged into collective acceptance without cynicism. Memories and images of war were passed along to the next generation and nurtured; layer upon layer of stories of heroism, combat, camaraderie, and harsh survival have been organized into mythology, where fiction and nonfiction merged.

Even though I was born a decade after the war had been over, I felt as if I had lived it viscerally with my family. A story was told and retold about street fights in Berlin and a soldier who saved my father’s life pushing him on the ground when he noticed a sniper. At a Victory Day holiday table, my grandfather gave a dramatic account of the liberation of Auschwitz (called Osventsim in Russian, as in Polish), and as a child, I was always captivated by the reenactment of his passing out at the horrendous sight. How many times did I hear a gripping narrative about his brother, who, gravely wounded, found himself stranded in Belarus on German occupied territory, cut off from his regiment? His life was saved by a villager, a simple Russian man, who hid him in his cellar. And I keep telling my children a story about my mother, who at thirteen stayed with strangers in a village in evacuation and who ran from wolves in the forest at night to bring her mother and sister some kerosene. [6]

On May 9, Victory Day, my Dad and I were always together for the celebration, the rally, and the reunion with his fellow war veterans: first, at the Soviet Army Square for a carefully orchestrated lineup to salute the banner of the 79th National Guard Mortar-Artillery Chernovitsy/Berlin Brigade, decorated with Suvorov, Kutuzov, and Bogdan Khmelnitsky Orders. One by one, at the drumbeat, the veterans approached the banner, kneeled, and kissed the flag. Some teared up. After the banner ceremony, a few veterans, my Dad included, gave talks at a local high school, which had been adopted by the brigade.

The Victory Day, 1968: Veterans of the 79th Artillery Brigade standing on and around the Katyusha (above)

and Yury Lvovich kissing the flag (below)

My childhood memories include a few of my Dad’s buddies as a steady presence in our life—they were always there when help was needed. They would raise money for each other’s families, provide “contacts” (the main currency in Russia), and give support. I remember the warmth of their presence and of their voices on the phone when Dad was sick. I called them Uncle Mark, Uncle Sasha, Uncle Yasha . . .

That was the “family romance” of the war, which extended its connections and affection to the next generation. Its ethos and sanctity served many purposes in the authoritarian state: it developed and maintained patriotism under the flag of nationalism; it cultivated stoicism and heroism, exception-alism and supremacy, and it helped adjust to material deprivations. Soviet food shortages and other chronic hardships of Soviet life could be forgiven as a minor sacrifice to peace. People who survived the war stood in lines for toilet paper and sighed with relief: Lish by ne bylo voyny! (As long as there is no war!)

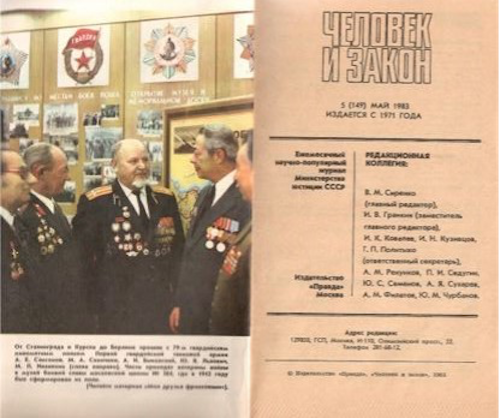

Among old pictures, which had traveled across oceans and time and survived immigration, I found an issue of an obscure Soviet magazine Chelovek i Zakon (Man and Law) that my father had brought to America with a picture of himself and his frontoviki (war buddies) on the cover. Here they are, in May 1983, all dressed up in their best suits for Victory Day, rows of medals clinking. The magazine features an article about them, the veterans of the 79th Mortar-Artillery Brigade, which includes this reminiscence:

. . . It was an endless surge of German tanks and mobile artillery, accompanied by the infantry. Explosions. Bombing from the air. No human being could survive this hell. But Katyushas created a real firewall . . . At the Battle of Kursk, Yury Lvovich’s platoon eliminated seven enemy tanks and three firing positions. During the war, he has grown and has become an experienced artillerist and a courageous soldier. At the battle of Kursk, he was a commander of a platoon and in Germany he commanded a battery. At the approach of Berlin, the battery of senior lieutenant Lvovich demonstrated outstanding performance and he personally showed phenomenal courage and excellent skills in organizing and directing the fire. His Katyushas were the first in the brigade to fire at the Reichstag. For his valor, Yury Lvovich was decorated with the order of Alexander Nevsky, the order of The Great Patriotic War of first degree, and the order of the Red Banner, as well as with many medals. [7]

I transcribed and translated into English the interview on the tapes, with his interjections, silences, laughter, and tears. I clustered the themes scattered throughout the interview. Here is his life, his family, and his war, in his own voice, perhaps a safe distance from my loss, slightly flattened by translation and time.

The cover of the magazine Chelovek i Zakon (Man and Law), May 1983. Yury Lvovich is second from right.

The Patched Pants

I grew up in Kharkov. Before the war and between my father’s arrests, we could hardly survive on my mother’s job as a clerk, my high school job as marksmanship instructor, and my uncles’ help.

I had one pair of pants (all my clothes were passed on to me from my older brother Goga, some were re-tailored from my father’s). Once, while I was playing outside, my only pair of pants ripped off at the knee, and it had to be mended, but the patch was visible. I kept my hand on my knee to cover it at all times. I don’t think my mother understood my shame, of that patch on my pants, of being poor, of being a Jew, and of being the “son of an enemy of the people,” the son of a traitor. Nobody cared if my father was innocent or not. Although there were quite a few families like mine, they lay low and never discussed it. It was dangerous to talk at that time. We lived in fear. Even my father’s good friends stopped saying hello to us.

I had great friends who often rescued me from my shame and from many embarrassing situations and helped me feel like a human being: Zorik (his father was the accountant-in-chief at a big hospital) and Sashka (his father was a lawyer). When popular actors or singers were on tours in Kharkov, tickets were expensive, about ten rubles. That was out of my league: I gave Mom whatever money I was making working as a marksmanship instructor at The Palace for Young Pioneers and as a volleyball coach; the rest I saved for cigarettes. So Zorik or Sashka would get an extra concert ticket, and then at the last minute they would call and say, “Yura, come on, get dressed, let’s go! I got an extra ticket! Petya was supposed to join, but he got sick.”

Goga and I made some good money playing cards. How did I spend it? On cigarettes and sweets. I couldn’t live without sweets! Once I even stole a silver spoon from my grandmother, sold it to Torgsin [8] and got myself a huge piece of cake. A piece of cake for a silver spoon, can you imagine? But it was an enormous piece . . . I couldn’t finish it.

Kyzylorda

Our troupes were withdrawing from Kharkov, and Mother, my brother Goga, and I evacuated to Kazakhstan, to a town called Kyzylorda. My father had been there already, in Kazakhstan, at a deportation settlement, after his third cycle of incarceration. Before the war, I had completed my freshman year of high school and in 1942 I was supposed to start my sophomore year. But we decided that instead of high school, I would go to the Railway Technical School located in Kyzylorda, primarily because it provided a worker-level food card. During the war, food was rationed; there were several levels of ration cards: the “worker card” was given to working people and had better provisions than the dependent’s card, which was given to students. At the time, the idea of getting a worker card was enticing, especially for a growing young man like me: I was chronically hungry; we didn’t have enough food.

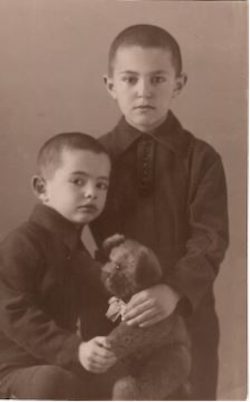

Yakov and Yulia Lvovich with children

Yakov and Yulia Lvovich with children

Children, from left to right: Yury and Gheorgiy (Goga) Lvovich

At school, I befriended some nice local folks who invited me to play percussion in their band. To be honest, I am not even sure I was that good, but I managed somehow. These were my happiest memories—probably because they were the last moments of innocent childhood. We played at the town dance, but we didn’t make much money there. The best profit however was at funerals. They requested smaller bands, so each of us could make more money.

Winter is severe in Kazakhstan: the temperature sometimes reaches minus thirty degrees Celsius. When we left Kharkov in September, it was still warm, and we had just one suitcase with us. I had managed to ship the luggage by train, elbowing my way through the crowd of evacuees . . . but the problem was, we received it a year and a half later. All our winter clothes were there. The only thing I had was my Dad’s light spring jacket, which did not help very much. I don’t know how I managed not to get sick.

Playing at funerals did not last. I couldn’t wait to join my friend Zorik and enlist together. He had been evacuated to Novosibirsk with his family and his father’s hospital and I suspected that they were making some extra money from medical alcohol. Zorik had his eye on the College of Military Transportation and Engineering in Novosibirsk. He thought it would be a good opportunity for both of us. I was eager to leave Kyzylorda and to join my friend, so I traveled to Novosibirsk and we were both admitted. When I returned home, I got a telegram from Zorik about the change of plans; he had been drafted and enrolled in horse-powered artillery school. The equipment dated from World War I or maybe from the Civil War; the army experienced shortages of competent military personnel as a result of mass arrests, gulags, and executions. We called the antiquated machinery poetically Proshchai Rodina (Farewell Motherlan). Farwell indeed: in 1942 the Red Army was withdrawing on all fronts, and soldiers were dropping like flies.

Zorik was critically wounded, and he did return to combat. I wanted to be with him, in artillery. So, I went to Novosibirsk again. His family knew someone who worked at the local Voyenkomat (Army Recruitment Office), and I hoped that he would help me convince them that I was a born artillerist, that artillery was my dream, and that I was a certified first-class shooter. But in the Recruitment Office they kept saying that they had no artillery training seats and that I would have to wait.

Stalingrad Battle Not in the Cards

While I waited for an order to report to an artillery school, an immediate draft call came in for General Gurtev’s Brigade, forming in Siberia, which was to be sent to Stalingrad. [9] It turned out to be the last unit to defend Stalingrad, the bloodiest of all battles, and I found out later there were only a few survivors from that brigade. Stalingrad was the breaking point of the war, so they drafted everyone they could, even completely untrained youngsters. Cannon fodder, that is what we were. I was drafted on the spot. They gave me a haircut, told me to pick up the uniform, and to report at 11 hundred hours to the train station.

I am always on the dot, and I was on the platform at eleven. But when I arrived, the train was leaving the station, getting smaller in the distance. It was overflowing with conscripts. Young soldiers were hanging from the train steps, waving and yelling their goodbyes. They were eager to fight and defend their Motherland. They did not know that they were sent to certain death.

I stood on the platform for a moment with a few others, perplexed. Nobody came to instruct us or to give explanations. We stood like this in the wind, bitterly disappointed to be left behind. We were told later that Gurtev’s Brigade must have been over-drafted. It was a miracle. This is how I did not die at the battle of Stalingrad. It was simply not in the cards.

Both photos:Yury Lvovich during the war (1941-46)

Artillery School: Twenty-Eight KP Duties

Next time I was summoned to the Recruitment Office, there were two tickets: one to the School of Army Management and another to Artillery School. Clearly, the Army Management would have been best—but I was a “born artillerist,” remember? I couldn’t change my story. So, I was sent to the Artillery School. The school was in Omsk, in Southwestern Siberia.

For two weeks we did not see any artillery, cannons, or mortar launchers. We were wondering what was going on. We went through the rigorous physical training regimen; they fed us well. Rumors had it that we would be trained for the Katyusha program (Katyushas were considered mortar artillery too). But I had my doubts: Katyushas had just come out of the assembly line and were classified for some time. I considered myself untrustworthy of secret weapons, especially if my status of “the son of an enemy of the people” was discovered. But it turned out I was wrong.

The deputy commander of my battalion, a real piece of work, took a dislike in me from the first sight and looked for any way to pick on me by assigning me KP duties (in retrospect I think he was simply an anti-Semite, which was normal in Russia). He would come in, look at me with unconcealed hatred, and say, “Another KP duty.” “For what? What did I do?” “You can address an officer only through your own commander. One more KP.” [10] By the end of the school year I had twenty-eight KP duties, mostly to wash floors. My battalion was stationed in a building with a gym, and soldiers would walk in straight from outside, smudging the mud all over the gym floor. When everyone crawled to bed, tired after a day of training, I headed to my floor-washing chore. I was quickly exhausted with sleep deprivation.

I quickly understood that washing that floor was a Sisyphean task. So, I came up with a way to deal with that: I would bring five buckets of water, pour four of them in the gym corners and one in the middle, wrap my foot with a cloth, and dance around the floor to spread the water. Then I reported to the commanding officer, who saw the glistening floor but was himself half-asleep, so I could go to bed for a few hours. Unfortunately, at some point, I got caught, and, it goes without saying, got more KP duties . . .

Soon it became clear that I wouldn’t be able to physically cope with all this, although they fed us well and I was young and athletic (before the war I had played volleyball for the Junior League of Ukraine). Once a week they showed us a movie, but guess what? I didn’t see any because once I sat down, I immediately fell asleep . . .

One day the school received some firewood for heating. These were whole trees to be unloaded, trimmed, split; then the logs had to be carried inside. All students were called in, including me. The following day it occurred to me that I could use it to my advantage: I went to the infirmary and said that I got hit by a log in the head and that I had nausea. I simulated a concussion and spent fifteen days in the medical unit: I finally slept, rested, and read. For meals, my battery marched in the cafeteria with a song, while I walked in and sat at a table to eat, like a prince. No doctors could really diagnose this. What can a neurologist see? Nothing!

The story goes on. On November 7, the holiday, everyone is off and having a good time—and I am in the infirmary. I was young, I wanted to party, like everybody else, so I said I was feeling better. They discharged me and let me go to the barracks. Everything was fine for a few days— until that bastard showed up again: “Do you remember how many infractions you have? You know what to do. Resume.”

I toiled all night, and the following morning was back in the infirmary, but this time they called in the Medical Evaluation Board. I knew nothing about physiology of course. I thought when they knock on your knee, the higher it jerks, the more nervous you are. So they took me to the Medical Board, a council of five specialists, who examined and palpated me and knocked on my knee—and I jerked it high. Believe it or not, they concluded that I had the remaining effects of a concussion and that I should refrain from attending classes for a month.

I Want to Go to the Front!

At that time an order came in to graduate two platoons and draft them to the front. I decided that I’d be better off sent to the front than staying at the school, where I was tortured. So, I went to see the battalion commander and told him that I had enlisted to the army as a volunteer to fight Nazis, not to wash floors. I told him that I had enough education and training to graduate from the program. Transfer me, I said. I want to go to the front!

He hugged me: “Comrade Lvovich! You are a great example to those lazy cowards! They just want to stay in the rear and hide from the battle.” He called my platoon commander and gave him the order to transfer me. I was allowed to accelerate my studies and take final exams. I passed all classes with excellent grades, all As, and graduated with the rank of Lieutenant. Upon graduation, I was even offered a position of an artillery instructor. But I’d had it with this school. I wanted to go to the front and was sent to Moscow to be placed as an artillery officer.

In Moscow, I was directed to the Voronezh Front, where the Commander of Katyusha Group was selecting officers. This guy was an eccentric character. A fellow in front of me walks in, and the commander asks him, “Have you had any disciplinary actions in school?” He says, “Nope.” “Not one?” “No.” “You never got in trouble with commanding officers?” “No.” “Well then, I don’t need you. Off to Leningrad Front.”

I walk in. He asks, “Any infractions in field artillery training? KP duties?” “Yes, twenty-eight of them.” “What for?” “The deputy commander of the battalion was picking on me.” “Nu khorosho! Good! You will be my Chief of Intelligence.” This is how I was assigned to Katyusha Group at Voronezh Front.

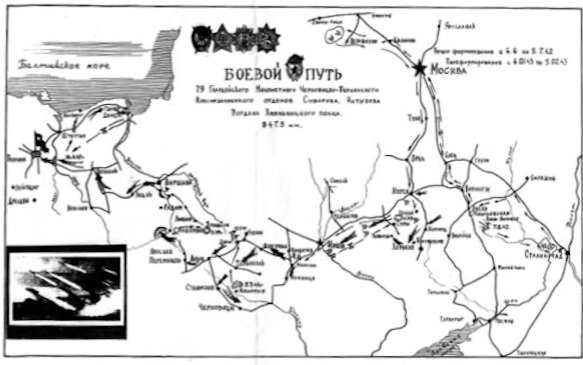

Combat Itinerary of the 79th National Guard Mortar-Artillery Brigade, Moscow-Berlin

My Brother Goga

My brother Goga (full name Gheorgiy) was not an ordinary person, although before the war, back in Kharkov, he seemed like a regular kid: he played volleyball and was an excellent student. He was leaning to the humanities; math was not his forte. I would often do his math homework for him, although I was younger. Yet he lived in his own world and, honestly, I could never understand that part of him. He was passionate about reading: when he read, he forgot where he was and what was going on around him. He was not here on earth, but there, in his books and in his head, and he would lose all sense of reality.

Once, when we were about to leave, he stopped in front of a bookcase, pulled out a book, and started reading. He stood there for hours, completely engrossed. I tried to call him and pull him out of it: Goga, let’s go! We have to go! But he wouldn’t budge. Sometimes he would lock himself in the bathroom and play there with a stick and a rubber band, whispering something. I often watched through the keyhole. I guess he was imagining himself an Apache Indian (we were all reading Fenimore Cooper and Thomas Mayne Reid). It seemed completely abnormal to me then: a boy playing all by himself in a bubble of his own imagination. I wonder if this intense life of the mind was prescient of his future escape of the war and of reality . . .

He graduated from high school before the war and entered Kharkov University, majoring in Language and Literature—German literature, believe it or not, during that horrible war! Although I learned German, too, like many others, and spoke it quite well, it was an entirely different matter to make it his major. It seemed that he was oblivious to reality.

Goga was my opposite in many respects: while I volunteered to the front, he developed a phobia of the war, a real panic, and did everything he could to evade the draft. In his attempts to do so, he had a “co-conspirator” and mentor, Yasha, our uncle, Lisa’s husband (Lisa, my mother’s sister). Yasha had been a big shot, a renowned journalist: the deputy editor-in-chief of Gudok, an important newspaper. He was a multi-talented brilliant person. In 1937—the climax of Stalin’s purges—he was assigned to cover the World Fair in Paris, but instead he gave it all up, got himself hospitalized with an ulcer, and retired from his editorial position at Gudok (which ended up being purged to the root by Stalin). He was bright enough to intuit that the intelligentsia, especially at ideological positions and especially Jews, would be eradicated (shot or left to rot in gulags), so he got on disability and withdrew from professional and public life. He knew that he and his wife would not be spared. In 1937 they took wives too.

Some people saved themselves by stepping back and laying low for a while, withdrawing from sight, especially big shots. They would be forgotten, somehow . . . Your maternal grandfather, Yefim, did the same thing. There were so many people to purge, to arrest, to remove. But for Yasha there was a cost: he lost it and became paranoid: he was convinced that Stalin’s secret agents were after him; he was always suspicious, always peeking out the window and around the corner. Once he told me there was someone perched on the telegraph pole to watch him in the window. Was there any ground to this obsession? I would never know. Anyway, Yasha was a genius: like a magician, he turned his life around, pursued graduate studies in Law, and together with Lisa and his sons evacuated to Kyzylorda, with us, where he taught at a university.

Goga was close to this smartass Yasha, who helped him plot how to dodge the draft. How could we two brothers be so different? I fought at the front; Goga had panic attacks just thinking of it. He had already had a deferment, but the situation at the front worsened and drafting intensified. I learned that Goga injected himself with various chemicals, including kerosene (all of this under Yasha’s tutelage). Some people cut their own fingers, shot themselves in the foot, ingested chemicals—and obviously harmed their own health. It may or may not be related to the fact, but at some point Goga caught brucellosis, a very serious disease. He was given a pass from the army. There, in evacuation in Kazakhstan, he met Raya and married her.

By the very end of the war, they moved to Moscow. He started looking for a Ph.D. program (aspirantura) which would accept him. [11] He contacted some Jewish celebrities, the famous writer Ilya Ehrenburg and the famous actor Solomon Mikhoels, later murdered by Stalin, and the latter supposedly said a good word for him, and Goga was accepted to Moscow University as a Ph.D. candidate and completed a dissertation on Heinrich Heine. His dissertation was written in German. Just think for a minute: writing in German and studying German language and literature in the wake of that horrific war, when all German words and sounds translated into one Russian word: hate. It was not a rational decision, but there was nothing rational about him. Perhaps he still lived in that fantasy world?

Goga never had a chance to defend his dissertation. His daughter Lenochka was born, and when she was only six-month-old, he got sick with pleuritis, which happened to be secondary to a quickly developing sarcoma of the lymphatic system. He died shortly. He was twenty-seven.

The injections and medications Goga had imbibed may or may not have been the real reasons for his tragic death. But I blame Yasha for making him take those chemicals and for passing on to him his own bitterness. I found out about my brother’s death from my mother’s letter when I was in Berlin, completing my demobilization paperwork.

Four Cycles

Once, when I was about ten, in Kharkov, my Dad and I walked by the building of the famous newspaper Pravda (“The Truth”). It was after my father’s second arrest and incarceration. I pointed at the building and said, “Look, the newspaper lies!” He blushed and read me a riot act which sounded like an article from Pravda. Was he truly loyal to the regime? Or did he want to make sure I would never repeat these dangerous words . . . ?

In 1921 my father, Yakov Lvovich, was arrested and imprisoned for participating in Es-er/SR activities [12] although he never belonged to any political party. He claimed that he had stopped by an SR meeting by pure curiosity and had quickly left. He was a soft-spoken quiet man, an accountant by profession, who worked hard all his life and did not take any part in politics. But it was a tumultuous time: no one could stand aside. That arrest was the first fallen domino piece, his first cycle. Since then, he was never left alone. Perhaps the trigger for his first arrest was his stay in France, where he had studied law at La Sorbonne, in Paris, in 1910.

In 1930 he was arrested again and sent to Berezniki, the notorious gulag in the “archipelago” described by Solzhenitsyn, then arrested again in 1938 and tortured in prison until he signed a confession corroborating somebody’s story that he was part of a plot to blow up a bridge near Dnepropetrovsk. He was never even close to Dnepropetrovsk. They attached him to the chair with his arms tied behind his back. His arm muscles were torn. They beat him with a metal ruler between the legs, an excruciating pain. We heard rumors that many Physical Education students had to be hired for the job because they did not have enough torturers. The country was choking in its own blood, innocent victims swiftly convicted by “troikas.” [13] Under torture, people signed fictional stories: a chain of narratives amplified the web of arrests and added new cycles of arrests and incarceration.

My father signed everything and was sent to five years in Kazakhstan (near Kyzylorda). That was his third cycle.

He was released in 1941, when the war started, but he was not allowed out of Kazakhstan. In 1942 we evacuated there from Kharkov; after I enlisted to the front, he, Mother, and Goga continued to live there. In 1951, he was arrested and sent to Siberia (Krasnoyarsk region) for ten years, his fourth cycle. He died in 1954. They had tried to give him the same verdict as in 1938, the one he had confessed to under torture, but he firmly refused to sign again. Therefore, he was sentenced in 1951 for attending the SR meeting in Kadievka in 1921 . . .

Mother accompanied him to Krasnoyarsk. She was lucky not to be arrested as a wife of “an enemy of the people.” After 1937, they started “taking” wives and children: the wives were sent to camps and children to orphanages, where their names were changed, so they didn’t even know who they were. My aunt Nadia, Father’s sister, was arrested when she arrived to visit her arrested husband in prison with a care package. He had been deputy director of Belarus Railways.

The Jewish Question

Soviet authorities knew about Hitler’s racial anti-Semitic doctrine and about the Final Solution; they knew what was happening on the occupied territories—and chose to ignore it. The whole world ignored it. It is not the Nazi state policy or their mass murder industry that brought European Jews to their death, and not general complacency. During the Nazi occupation, Estonians and Lithuanians reported to the Germans that they had already “solved” the “Jewish question” without them and before them. It was the Poles and the Ukrainians, not the Germans, who led 80% of all anti-Jewish operations.

Jews who managed to flee the Nazis were often surrendered to the Gestapo by local people, and those who escaped tried to join guerrilla resistance (the partisans) who were hiding in the woods and conducting subversive commando operations. I heard that those losers, the partisans, damn anti-Semites, would not take runaway Jews in. Many perished as a result. Ah! They would have been better off at the front, like me, fighting in the army. Many Russian soldiers had never seen Jews in their lives and never knew the difference; they were innocent, like children.

So, no, I have not experienced anti-Semitism in the army. My commander respected me and counted on me, maybe more than on any other person. Perhaps, had I not been a Jew, I would have had more opportunities, but it did not occur to me then. For example, I could have been promoted by the end of the war to be a company commander. And my nomination for the highest award The Hero of the Soviet Union might have gone through . . . yet I got instead The Order of the Great Patriotic War, first degree. I was nominated for The Order of the Red Banner for street fights in Berlin — and got The Alexander Nevsky Order instead. It was normal practice to be awarded a lower decoration than the nomination, so it would not be fair to say it was because I was a Jew.

Vacation Pay

When the war ended, it did not mean that we went home right away. Soldiers and officers continued to serve in the Occupation Group. Some were sent to Japan; my brigade stayed in Berlin (until it was disbanded in 1946). There were no zones or walls in Berlin yet; we were free to move around. Two officers from my brigade “borrowed” a car from some garage and drove to Paris . . . then, when they returned, they boasted about it, like complete idiots, and they were reported to SMERSH [14] and dishonorably discharged . . . Thank G-d they were not shot!

Once the military unit is disbanded, every effort is made to attract skilled officers into regular army and to make them stay with a decent salary, a promise of a career, and other incentives. I was called in as well. But this is when I got news of Goga’s death. I felt I’d had it; I completed my demobilization paperwork and left for Moscow.

It was a strange, almost unreal experience . . . One of my army friends, Gleb, who was the brigade Komsomol leader and later became a big shot in the city government, was my companion. We would meet every night at a restaurant. We would order 900 grams [15] for two, but then he would add 100 grams for dessert—and I would order an ice cream. And every night I would carry him home, unconscious, and every night he said, “Tomorrow I am carrying YOU.” We never lived up to that moment.

Ironically, the money we were drinking off was our “vacation pay” that we had received for every year of the war. As far as I know, in German army, even during the heat of the war, every soldier went on vacation leave, according to the army schedule. To them the war was an enterprise, not an act of monstrosity. But for us of course, the war was nothing but an evil attack on our land and people, and we gave our bodies and souls to defend ourselves. We laughed our heart out when we got this accumulated “vacation pay.” We drank it off within a month.

There were special privileges for the discharged military personnel, and one of them was admission to universities without entrance exams, usually extremely competitive, especially for Jews. Regardless, my high school diploma was with the “gold medal”—the Soviet equivalent of cum laude—and I became a Law student.

I stayed at my aunt Lisa’s for a while and slept on a tiny couch, bent in a pretzel. I was dirt-poor, with my student stipend and a small war veteran disability pay. When I couldn’t take it anymore at Lisa’s, I rented “a corner” from two old women at Smolenskaya Square. The room was a walk-through and had no door. Moscow was still hungry, and I was very thin. The sweet old ladies had no family and took good care of me. They worked in the U.S. Embassy, one as a maid and another as a cook, and they brought home some goodies. They saw that I didn’t eat and fed me every day. I will never forget tea made with American lemon powder, which tasted like real lemon. I will never forget their kindness.

I was completely alone in Moscow. Mother was with my father in Siberia. When he died in 1954, I was already married. I went to Krasnoyarsk and brought her with me to Moscow; she had no place to live and no money . . . You know the rest.

✤ ✤ ✤ ✤

1. Translation is mine

2. When the December 1825 uprising against the monarchy in Russia (led by a group of aristocrats nicknamed Decembrists) failed, some of them were executed and some exiled. Several Decembrists’ wives heroically followed their exiled husbands to Siberia (e.g., Maria Volkonskaya, the wife of the revolt leader, Sergei Volkonsky). The expression “Decembrist wife” is a Russian symbol of the devotion of a wife to her husband.

3. “An enemy of the people” (vrag naroda) was a common designation of a person arrested and accused of an act of terror, espionage, or treason against the Soviet people. Although Stalin’s regime proclaimed that children are not responsible for their parents, the surviving children were designated as a son or daughter of “an enemy of the people,” a stigma which carried an obstacle for their social and professional development.

4.“For Motherland! For Stalin!” was a popular slogan cultivated by the Red Army, which soldiers launched into battle during World War II.

5. The invention of the Soviet legendary mobile artillery unit Katyusha is said to be inspired by the first “super-gun” called machine infernale, invented by Giuseppe Fieschi, the chief conspirator in the attempted assassination of King Louis Philippe of France in 1835. The rumor had it that Fieschi was honored in a secret religious service in 1942 in Moscow, at the request of Soviet General Kostikov, one of the inventors of the Katyusha rocket launcher.

Officially coded BM-13, Katyushas became military “stars” of World War II; their legendary glory was said to be a decisive force in the shift toward victory. Katyushas could deliver several tons of explosions to an extensive area in just a few seconds. The fire power of such a salvo was comparable to that of seventy heavy artillery guns combined, and their mobility gave the Katyushas an import-ant advantage (the rockets were mount-ed on ordinary trucks—after 1942, American Studebaker trucks). They remained top secret until the end of the war: each was supplied with an explosive for self-destruction, so that no single machine would fall into German hands.

Since they were marked with the letter K, for the manufacturer named after KOMINTERN, the soldiers nicknamed the weapons “Katia” (Yekaterina), a popular girl’s name, whose endeared diminutive is Katyusha. During the war, this name was stamped into the Russian national consciousness as a symbol of Russia itself, popularized in the form of a folk song based on a poem by the well-known Soviet poet Mikhail Isakovskiy. Easy to remember, sung by popular singers and choirs on the radio and in concert, and enjoyed at campfires and marches, the song was adopted by the whole country, featuring unassuming lyrics about a Russian girl’s love for a soldier who defended his country and who was expected at home with love.

The legendary Soviet rocket launchers carried a strong patriotic meaning with their lethal destructive force and was particularly feared by Germans. Because of Katyushas’ unmistakable wailing sound and their shape resembling an organ, the Wehrmacht ruefully dubbed the weapon Stalinorgel (Stalin’s Organ).

6. Balakovo, Post Road, No. 18, 2010

7. Translation is mine

8. Torgsins were state-run hard currency stores that operated in the USSR in the 1930s. Torgsin is an acronym of торговля с иностранцами (trade with foreigners).

9. The Battle of Stalingrad, 1942-43, was one of the deadliest battles of WWII, with 1.25 million casualties, which marked the turning of the tide of the war toward the Allies.

10. KP—kitchen police or patrol (U.S.), extra work in the kitchen or any chore assigned to junior military personnel.

11. There was an enormous competition to enter a Ph.D. program at the Department of Philology at Moscow University (the prestigious Philfac), which had an (unofficial) quota for Jews. On top of that, the chances were almost null for a “son of a traitor.”

12. SR (Es-er)—Socialist Revolutionaries, a political party, key player during the Russian Revolution, who were defeated by the Bolsheviks. During the subsequent years, as “the dictatorship of the proletariat” was established by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, all dissent (former SRs and the Mensheviks) was eradicated.

13. “Troikas” (trios) were “special commissions” of three judges, instituted by Stalin, to speed up indictments and sentences.

14. СМЕРШ, an acronym, literally Смерть Шпионам (Death to Spies), the Soviet Army counter-intelligence agency, which court-marshaled and shot thousands of military men.

15. In restaurants and bars in Russia, vodka is dispensed in grams

Natasha Lvovich

Natasha is a writer and scholar of multilingualism and literature. Originally from Moscow, Russia, she teaches at City University of New York and divides her loyalties between academic and creative writing. She is the author of a collection of autobiographical narratives The Multilingual Self and of numerous pieces of creative nonfiction and essays. Her work appeared in journals (Life Writing, New Writing), anthologies (Lifewriting Annual, Anthology of Imagination & Place), art reviews (Full Bleed) and literary magazines (Post Road, Nashville Review, Two Bridges, bioStories, NDQ, Epiphany, New England Review, Hippocampus Magazine, Jewish Fiction); one of her CNF pieces has been nominated for Pushcart Prize. She is Senior Reader for Hippocampus Magazine; her essay commemorating 9/11 is forthcoming in Massachusetts Review. She is founder and Editor-in-Chief of a new academic Journal of Literary Multilingualism, published by Brill.