Editor’s Note: This publication marks the launch of Consequence Forum’s newest series, the Young Writers & Artists Project. The follow three pieces are in collaboration with Teens in Print (TiP), a writing program directed by Mohamed Barrie that encourages and celebrates the marginalized voices of Boston’s eighth- to twelfth-grade students. TiP is also part of WriteBoston, an org focused on fostering deep learning for youth and educators.

These posts were coordinated by TiP’s Youth Leader, Grisha Leyfer, and are interviews (or essays based on interviews) by young journalists with individuals who were or are part of Harvard University’s Scholar’s at Risk (SAR) program, a program that helps scholars and artists from around the world escape persecution by providing academic fellowships at Harvard. The Director of SAR, Jane Unrue, is also a Contributing Editor for Consequence Forum.

✶ ✶ ✶

A Conversation with Sima Samar

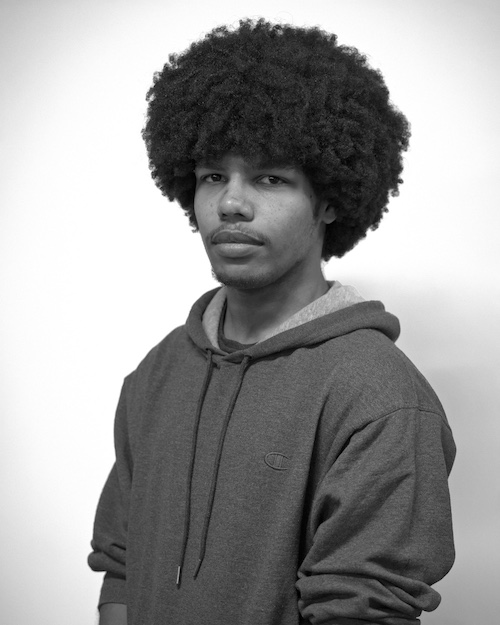

By Sandro Tavares Jr.

Personal Statement from Sandro:

When I saw that I would have the opportunity to speak with such a high profile person like Sima Samar, I was very surprised. After all I’m just a teenager who writes stories about what books I like to read and about local events. I was very worried because I don’t know much about anything that happens overseas, unless it’s something that everyone is talking about, but a lot of this happened when I was younger or before I was born.

I tried to get a basic understanding of the situation before my interview, but I was still worried; after all I’m talking to the former Deputy President and Minister of Women’s affairs of Afghanistan. Once I got the chance to talk to Dr. Samar, though, she was actually very easy to talk to. Maybe that should have been obvious, since her job revolves around talking to people, now that I think about it.

Getting to talk to someone who actually lived through this also put into perspective for me that everything I read about while researching happened to actual people. These things aren’t just words on a page or an interesting story but the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

*

For the past forty-five years, Sima Samar has been using education to fight against the cycle of hatred that has been perpetuated in Afghanistan. Since graduating from university in 1982 as a medical doctor, she has been doing humanitarian work to aid women in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In my research I learned that Afghanistan has been dealing with the aftermath of a proxy war between the US and the Soviet Union since the 1980s, when the Soviet Union launched an invasion of Afghanistan in order to defend the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA) from the Mujahideen, a US-backed, conservative, guerrilla group which was trying to overthrow their pro-communist government. After her husband was arrested by the DRA, Samar and her son sought refuge in Pakistan. “I moved to Pakistan because I had to,” Samar explained. “I had a son, and there were no possibilities for education other than being a refugee in Pakistan.”

Dr. Sima Samar with a group of young women in Daykundi in 2003.

Dr. Sima Samar with a group of young women in Daykundi in 2003.

While in Pakistan she worked in a hospital helping refugees, and witnessed firsthand the discrimination that Afghani refugees faced. “A doctor who was my colleague . . . was always saying ‘these dirty Afghans,’ and I [would argue,] ‘Yes, but we are forced to come here. We did not come here for a picnic.’”

In 1989 she established a girls’ clinic for Afghan refugees in the Pakistani city of Quetta, where she trained medical staff, provided healthcare to the women, and educated them about reproductive health. She tried to publish a book she wrote for the girls to learn from but was stopped by a UN worker. “He said, ‘We do not print any religious issues.’ I said, ‘There is no religion in this book. It’s just health education, it’s really simple.’ He replied, ‘Sima can you leave the book here and come [back] next week? I will ask . . . my Afghan colleague to read it and see if we can help you.’” When she returned, he told her, “We cannot print it . . . because you’re talking about contraception and family planning. . . . We cannot do that because the fundamentalist Mujahideen group will bomb our office.”

The Mujahideen eventually won; in the early 90s they overthrew the DRA which created a power vacuum which led to four years of civil war between various groups including Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin (later the Taliban and Al-Qaeda), Hezb-e Wahdat, and Junbish-i Melli. The four-year civil war in Afghanistan ended with the Taliban taking control of Kabul along with most of the country. This lasted until 2001 when, following the 9/11 attacks, US president George W. Bush ordered the US invasion of Afghanistan in order to stomp out Al-Qaeda, the group responsible for the attacks.

For the next twenty years, while the US fought the Taliban for occupation of Afghanistan, an interim government was established where Dr. Samar served as deputy president after returning to Afghanistan in 2002. She later served as the first Minister of Women’s Affairs, a government position dedicated solely to advocating for the protection of women’s rights and wellbeing in Afghanistan. From 2002-2019 she led the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), an agency which sought to defend and promote human rights as well as looking into human rights violations.

Having had the opportunity to speak with Sima Samar, it’s clear that she places great value on education, and the role that the lack of it plays in the violence in Central Asia. She told me, “Put yourself in the shoes of someone [with] a daughter [who] is not allowed to go to school. And then at the age of twelve, she’s already given [in] marriage to someone because there’s not anything else. And then the impact that from [the] age of fourteen, she [gives birth to] children [until] the age of fifty. . . . Uneducated, unemployed, young men are frustrated. They join the terrorist groups, the girls are victims of domestic violence and forced marriage, child marriage. And the whole cycle continues repeatedly.”

This leads Dr. Samar to the conclusion that, in order to create peace, it is vital to protect the rights of women not only in Afghanistan but around the world, because the organizations that form in places where citizens aren’t treated with dignity have effects far beyond the country where they formed. “If you hear [about] the people who are killed [at] the border between Iran and Turkey, the majority are Afghan; if the ship sinks, close to Greece or Italy, the majority are Afghan. [This is] because women [don’t] have access to reproductive rights. First, they don’t have the information because they don’t have education. Secondly, they don’t have access to contraception.”

In August 2021 the US pulled their military troops out of Afghanistan. When this happened it was made painfully obvious that, on top of Osama Bin Laden (the leader of Al-Qaeda) not even being in Afghanistan, our reconstruction efforts also were a resounding failure, as the Taliban was able to retake the country within ten days of our withdrawal despite twenty years of pouring money into their infrastructure and military. To me this means that we basically went there for no reason.

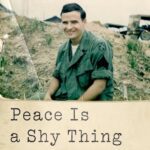

When the Taliban retook power in Afghanistan, Sima Samar was visiting family in the US. Since then she has remained in Massachusetts and worked with Harvard’s chapter of Scholars at Risk. This program at Harvard and at universities across the country supports scholars who are unable to safely continue their work in their own countries, by giving them research and teaching opportunities in the US. Since coming to the US, Sima has been working on a book that has since been published (in February). It is a memoir detailing her life as a doctor and public official, her advocacy for women’s rights, the founding of schools and hospitals, as well as giving the reader a view into her life during the war. “I have gone through a lot of difficulties in my life and suffered a lot during these forty-five years of war in the country and being in danger.”

Dr. Samar makes clear that the situation in Afghanistan still hasn’t been resolved: women haven’t gained equal rights, the Taliban hasn’t been taken out of power, and we seem to have stopped talking about the situation very quickly. But the US is still probably the most capable of doing something about the situation, and it is largely our responsibility due to over forty years of funding and intervening in their government. So what should be done moving forward? Dr. Samar says, “I think it should be a clear, clear message to the Taliban, for accountability on [the] commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including [what we call] gender apartheid, discrimination against women. . . . It should be clear that they should not negotiate on [the] principle of human rights. If you do not respect human rights, what are we fighting for? . . . I think the strongest tool for sustainable peace is the respect for implementation of human rights principles in any country, not only in my country, in any other country, including all these wars going on around us. . . . We should look at the mistakes that we’ve [made] in the past and learn from those mistakes. And denial of the problem in Afghanistan is not helping anyone. . . . If you deny the problem, we cannot find a solution for it.”

✶ ✶ ✶

A Conversation with Beeken Erena

Personal Statement from Fiona:

Before talking to Beekan Erena, I didn’t know anything about what was happening to the Oromo people in Ethiopia. I wasn’t aware of it due to the news I watch, and the social media I consume has never spoken about it. Recently, I’ve only heard of a select few major conflicts, all of which are important, but what’s also important is sharing and discussing the other conflicts in the world that happen more quietly. That’s why I’m grateful that I was able to learn about Beekan’s story. It opened my eyes to what I don’t know about this world and encouraged me to learn about it. I hope it does the same for you, too.

*

“Growing up as an Oromo person in Ethiopia has been a testament to resilience and an unwavering commitment to my identity and dreams.” This thought is shared by many Oromo people but especially by Beekan Erena, an Oromo advocate. The Oromo people have been oppressed for decades despite being the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia. Oromo land has been seized at times by the Ethiopian state and dominant ethnic groups. This led to widespread displacement of the Oromo people and conflicts over land rights. The Oromo language, Afaan Oromo, has also faced suppression, limiting opportunities for Oromo people. One of these limited opportunities is schooling. Due to the language barrier and prejudice that Oromo students face, it is difficult for them to get their education.

Beekan Erena told me that he has personally been a victim of this oppression. But he works endlessly to fight it through writing and teaching. He currently is living in the United States pursuing a graduate certificate in Learning Design and Technology with the goal of becoming an expert in technology and digital skills, focusing mainly on online teaching and iCLOUD technologies. At Harvard, he is working as a Pathways Assistant where he manages inquiries of graduates, alumni, and employers. He also provides support to staff members and deals with issues on Salesforce and Hub. When he is not doing either of those, he does literary writing.

But before living in the United States and working at Harvard, he grew up in Nunu Kumba, a small village in Oromia. He had a joyous childhood despite the limited access to modern amenities and fearing the presence of the government and its security forces. But he was determined to rise above these challenges which only “fueled [his] determination to succeed. Education became the beacon of hope, offering a way out of the cycle of poverty and discrimination.”

He went on to attend prestigious universities in both Jimma and Addis Ababa. His university life “ushered in a series of cultural adaptations and challenges” due to the change from a small, familiar village to an environment crowded with over 20,000 students from different ethnic groups. Despite this, he formed lifelong friendships while remaining true to his Oromo identity. Afterwards, he became a university teacher in order to “empower other Oromo [students] through education.” This also proved to be difficult due to security forces trying to silence his voice, but he continued to teach in the Oromo language and to preserve their culture and heritage.

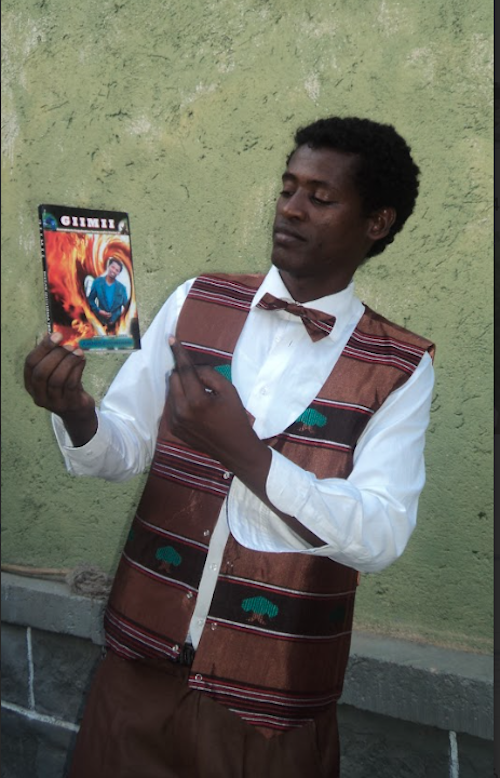

Beekan began to advocate for the Oromo people through literature. In March 2012, he published a book titled “GIIMII.” This book was a collection of narratives that used farm animals to represent the harsh realities faced by the Oromo people. His effort to advocate did not go unnoticed by the Ethiopian government, and in April 2012, he was abducted by Ethiopian authorities and taken to a secluded office near Ambo University. Here he was subjected to interrogation in order to extract information about his literary works. Despite this, he remained determined to “be the voice of the voiceless Oromo population.”

His advocacy started to get attention, but not in a good way. His works were censored by the government and a few even got banned. The Ethiopian government went even further to silence Beekan through physical and psychological torture and constant threats. Due to the government’s relentless interference in his studies, Beekan was terminated from his positions and had to abruptly end his doctoral studies. In 2015, Beekan came to the conclusion that there was no future for him in Ethiopia.

During this time, Beekan received information from a friend studying at Harvard, which led him to discover the Scholars at Risk program, a fellowship that allows scholars facing persecution to continue their studies in a safe environment. After many interviews, he got accepted into the program with the guidance of the program’s director, Jane Unrue.

When he arrived in the United States, he was greeted with “warmth and genuine hospitality” from the team at Scholars at Risk and the community at Harvard. His goal while in this program was to continue to advocate for the Oromo people at a larger level. He wanted to achieve this by preserving the Oromo culture and language from marginalization, which he was able to do by teaching it through the Harvard University League. He also continued his research by being a visiting scholar, carrying out his own work in association with a faculty member. Beekan’s research revolves around the struggles of Oromo students who fought for justice despite the violence the Ethiopian government inflicted upon them.

Beekan shared that the program has played a “paramount role” in his life. He was able to do his studies safely without the constant fear that he had while in Ethiopia. He also enjoyed that he was able to meet people of diverse backgrounds and participate in academic discussions. Despite the sense of safety the program gave him, he always carried the weight of fearing for his family, friends, and the entire Oromo community. But he took comfort in the fact that he was in a better position to advocate for the Oromo people.

After Beekan finished the Scholars at Risk program, he applied and was accepted into the Global Inclusion & Social Development PhD program at UMass Boston in 2017. He was unable to attend for financial reasons—and the need to support his family—and opted instead to work while pursuing graduate certificates in technology at Harvard. He is still optimistic and believes the graduate certificate courses “serve as a valuable stepping stone towards [his] future pursuit of a doctorate in Educational Technology.” When he is not pursuing a graduate degree, he works on literary writing.

Beekan shared that he has not returned to Ethiopia since becoming a research fellow. This is due to the threats he faces on social media, where he advocates for the Oromo community on a larger scale. After all of the work that Beekan has done and continues to do, he hopes that it changes the world—especially the relationship between Ethiopia and the Oromo people—for the better. He also hopes that his work inspires others to take action and fight for justice and equality.

In the future, Beekan hopes to create an online digital teaching platform. Through it, he could reach millions, making quality education available to all. He also wants to motivate generations by drawing inspiration from biblical scriptures. Similarly, he wants to provide guidance that aids people coping with stress, depression, and anxiety, while simultaneously preparing them for spiritual enlightenment.

Beeken is just one of the many Oromo people who faced oppression by the Ethiopian government. But, in recent years, the Oromo community has begun to protest for recognition of their rights and redress of historical grievances. This led to the appointment of Oromo Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, in 2018. He aimed to make the government more inclusive and address historical injuries the Oromo people faced.

Even with all of the improvements in how the Oromo people are treated, they still face challenges over land disputes and political and cultural representation. But people like Beekan are working to someday change this relationship between the Oromo community and the Ethiopian government. Despite this relationship being long and difficult to understand, Beekan says, “In understanding the complexities of this connection, young dreamers and future leaders can draw inspiration from the resilience and unwavering determination of the Oromo people, using their experiences as a foundation for advocating for justice, equality, and positive change in the world.”

✶ ✶ ✶

A Conversation with Mastora Shafahi

Reflection from Sivan:

1. What was the most memorable moment of the interview for you? Learning about Mastora’s backstory regarding gender inequality under Taliban rule was inspiring, as well as learning about how she escaped from prison. It was meaningful being able to empathize with Mastora in a women-to-women conversation, learning about the Hazara genocide’s impact on the lives of women and her ability to speak so powerfully about her experiences after living in a country where the voices of women are silenced.

2. How much did you know about the situation(s) your interviewee described before doing this interview? Why do you think you did/didn’t know what you did? Before interviewing Mastora, I was aware of the situation in Afghanistan and the treatment of women under the Taliban. From Mastora’s words, I was able to better comprehend the effects of the Hazara genocide, and the firsthand experiences of having your identity taken away from you, after living a fairly well-balanced life of freedom.

3. What was the emotional experience of conducting the interview like? Conducting the interview felt like I had the power and responsibility to build and comprehend someone else’s story, in this case Mastora. There has never been a moment where I felt genuinely more comfortable and proud to be a woman. Mastora drove me away from my egos of daily life and helped transport me into her shoes, each moment revolving around the past, present, and future.

4. Has your perspective on anything changed? Is there anything new you plan to do/something you plan to do differently now? After hearing a brave Afghan-Hazara midwife’s incredible story, I cannot look away from human rights issues happening around the world, especially stories about Afghan women and families. Since Mastora’s story gave me a clear and defined understanding of my power as a free woman, I feel motivated more than ever to hear the stories of other people firsthand. As a journalist, I will analyze their experiences, take them into account, and use the pen to others to build awareness.

5. Did you find similarities with your own/your family’s experiences? Alternatively, if you found primarily differences, what makes you think about your own/your family’s experiences? As a seventeen-year-old girl living in America with the right to education and freedom, I could not make out Mastora’s and my experiences to be similar. However, despite our different experiences, we were interested in each other, and learning from one another. She is Hazaran and is a minority in the Afghanistan population. I am Jewish and my ancestors in Europe were targeted for their cultural beliefs and ethnicity. Genocides, like the Hazara genocide, and the Holocaust, are driven by hate, and I’m lucky that I have never experienced genocide or military rule. However, being lucky and grateful to be free, does not give me the privilege to not help women in Afghanistan. Both Mastora and I have dreams and have always had dreams since we were young, and right now we are pursuing what we can.

*

Nearing the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, Mastora Shafahi, a renowned Afghan midwife, ran for her life as she fled her home, now occupied by the Taliban. She needed to reach somewhere safe, even if that meant crossing the Taliban-controlled border by foot. The strength of the mountain wind caused her headscarf to wave. Nonetheless, her eyes trailed the red-marbled mountains as she walked. Freedom was guiding her. The next minute an unsettling sound erupted, and she was faced with armed soldiers. Their faces were completely enveloped with jet-black face-scarves. In assaulting voices, they demanded her personal information. Their eyes narrowed in disapproval, and she was detained to a cold and inhospitable prison cell.

All at once, Shafahi was desperate, belittled and scared. Yet she did not lose hope.

For Mastora Shafahi, Bamyan Province, filled with blue streaming waters and orange-marbled mountains, is home. A childhood with strong and hardworking women made Shafahi appreciate the occupations reserved for women in Afghanistan. She saw mothers and grandmothers deliver babies with their bare hands. Childbirth at home or in small local hospitals was how most births were conducted in Afghan villages. She wanted to help women in her country actively by aiding them in completing their families and ensuring their right to health.

Once she completed her primary school education, she left her small province for the University of Kabul where she studied pharmaceutical research and midwifery for four years. Once she received her Bachelor of Pharmacy, she earned her master’s degree in rehabilitation sciences at the University of Dhaka in Bangladesh. “I did this so that I could specifically support women in Afghanistan,” said Shafahi.

Her advanced experience in the medical field led her to serve as the general manager of the Afghan Ministry of Public Health, a UN-based establishment focused on providing advanced medical care to Afghan citizens. Shafahi informed the ministry about providing safe births through using the midwifery techniques she learned and strived to make the community of midwives in Afghanistan more unified in their methods. She also advocated for equal access to educational opportunities and worked to provide scholarships for Afghan women pursuing a career in the medical field.

She put detail into each one of her ideas, especially when ensuring proper access to medicine and health products for all genders. Most of all, she wanted people to feel the changes she implemented.

Despite having a high position in the medical field, she identified the various flaws within her country’s medical setup. Her unique perspective allowed her to see how women in less powerful positions were limited in midwifery and other medical fields. According to Shafahi, in Afghanistan, women are traditionally discouraged by their husbands from working, which means that hospitals and medical facilities were mostly male-dominated. Since she was not married, Shafahi lived in a “widowed facility,” a shelter that housed unmarried and widowed women. Shafahi did not feel at home or respected during her time there. “All the time, most of the people punished me because I was a woman who wanted anything.” They often ridiculed her, questioning: “’Why do you work outside? Why do you continue your education?”

Strict Islamic law worsened as soon as Kabul fell to the Taliban on August 15th, 2021, following the US military withdrawal from Afghanistan. The Taliban, a Sunni Islamist nationalist group, occupied province after province in Afghanistan, continually regrouping until they achieved full control of the country. With the Taliban taking over, resources for healthcare, employment, and educational resources significantly diminished, putting Shafahi and other doctors in positions where they were severely restricted and understaffed. Since the takeover, the Taliban have released fifty-four edicts restricting the rights of women. Two years on, they have succeeded in prohibiting women from visiting most public spaces, including parks, gyms, and beauty salons. Most importantly, girls over twelve are prohibited from pursuing education, and women have been banned from most careers. Every day, Shafahi worries about her sisters and family members living in Afghanistan. “It is really hard for girls. For more than two years [my sister] hides. She is not allowed to go outside.”

Shafahi’s family was under increased danger due to their Hazaran ethnicity. The Hazaras, an ethnic group native to Afghanistan, have been subjected to genocide and exclusionary acts barring them from living in the region. The climate of ethnic nationalism leading to the Taliban’s takeover drove a hate campaign, resulting in increased threats toward the Hazara people. “Most Afghan people try to kill a lot of people [Hazara] because they think they are not Muslims. We are different. We are not from Afghanistan. . . . They are killing Hazara, they are killing men as well as they are killing women Hazara, they are killing educated Hazara . . . six months ago sixty-eight Hazara girls were killed, because Hazara people, they like freedom, they like to respect all people.” Shafahi was among the Hazara who took a strong stance on these values and feared the possible risk of persecution.

Shafahi’s family still in Afghanistan do not feel safe leaving the house, due to uprisings and hazardous incidents. Three years ago Hazara’s younger sister was a victim. Due to her passion and support of Hazaran values she was abducted by an unknown person. It has been almost three years, and Shafahi and her family still do not know the location of her sister. Shafahi highly believes the abduction of her sister was due to her sister being a Hazara woman.

Even before the Taliban takeover, amid turmoil, extreme sexism, and harassment due to her profession, Shafahi had an exit plan in mind. She knew her country could be in a shaky and unstable situation at any time.

Before the uprising, she had found the Scholars at Risk program.

“I applied and, because of my background and education,” including her work for the Ministry of Public Health and her activism on social media, “they accepted me,” said Shafhai. Now she needed this opportunity more than ever.

Shafahi spent the whole day at the border in a room with a hard-rock floor and a thick white plastered wall. Luckily, there was still an electronic item with her that they had not taken away.

It could help. The phone.

Shafahi scrolled through her contacts list until she found Jane Unrue, Scholars at Risk’s program director at Harvard, and called, hoping for a response.

After a single tone, Unrue answered. In an urgent situation, Shafahi didn’t even have time for “Hellos” and “Where are yous.” She informed Unrue of her current location, saying that she feared for her life. Unrue, who had experience with such high-stakes situations, called an Afghan friend who managed to bail Shafahi from prison. The plan worked smoothly. Shafahi rushed to reach safety in Pakistan. She took temporary refuge in Dubai until everything was set up for her arrival in Cambridge. In May 2022, she began her job at Harvard as a part-time research fellow.

Unlike the typical job setup, Shafahi’s work takes place during the night. Every day after sunset, she works for UN WOMEN. She represents a vibrant voice for the cause of women’s rights in Afghanistan. Shafahi says that most people know about her support, as she is “married” to the organization. There are different working set groups separated based on occupation, in sponsoring these projects, including a midwifery and physician set group. As of right now, Shafahi is advocating for equal pay for women in Afghanistan. She is planning to achieve this goal by sending in resolutions to the UN that urge organization leaders to bring new policies into businesses and organizations in Afghanistan. Along with a friend from Canada, Shafahi is working on a project for International Women’s Day, with help from the United Nations, to raise awareness of the harsh realities of how the Taliban rejects the autonomy and freedom of women, and to bring together women impacted by the situation. Shafahi also works with other women in the same group to set up programs that work toward creating a movement in line with her Women’s Day project.

Shafahi makes it clear when talking to the UN and various human right organizations that “the men in Afghanistan, the Taliban, do not respect women. They treat women like they are all the time at home. They do not treat them like human beings.”

So far, Shafahi feels at home and welcomed in the Harvard Scholars at Risk community. “It has been very good for me. When people move to another country, everything is strange; for me everything was easy. Everything was very straight and lovely.” Shafahi has learned a lot through the support of her colleagues and mentors. She is especially grateful for Jane Unrue, who helped rescue her when she was under arrest. Now that they have finally grown to know one another, Shahafi describes Jane as simply “amazing.”

America is a safe haven for Shafahi. It is different from Afghanistan, as both women and men are encouraged to pursue their own professions. She feels safe and secure and enjoys her colleagues and friends who keep her going every day. Most importantly, she is pursuing the ability to experience her education freely without repercussions.

Despite living in an accepting and free country, she has never stopped thinking about her family and the terrifying environment for women in Afghanistan under Taliban rule. She knows it is in her hands to guide the Western world to understand what women in Afghanistan are forced to endure every day. Through her work, she knows that she is leading change for women across the globe, building a better world not only for herself but on behalf of all the women out there with dreams of living in a free world.

Teens in Print

Teens in Print (TiP) is a writing program created to amplify the marginalized voices of eighth to twelfth grade Boston students. We strive to give students the tools to share their experiences and perspectives through writing, the platform to reach decision-makers who can act on their ideas, and the knowledge to become thoughtful consumers of media. @teensinprint

The Scholars at Risk (SAR) Program at Harvard is dedicated to helping scholars, artists, writers, and public intellectuals from around the world escape persecution and continue their work by providing academic fellowships at Harvard University. Risk may be related to the scholar's work, but it may also be a consequence of other factors, including the scholar's ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, identity, or political opinions. Founded in 2001 as an independent member of the International Scholars at Risk Network, SAR at Harvard relies on the generosity of private donors and the Office of the President to carry out its crucial and often life-saving mission.

Consequence Forum’s Young Writers & Artists Project is supported by a grant from the First Parish UU church in Cohasset, MA.