Young Writers Nonfiction Project: 2025 Journal

About Consequence Forum

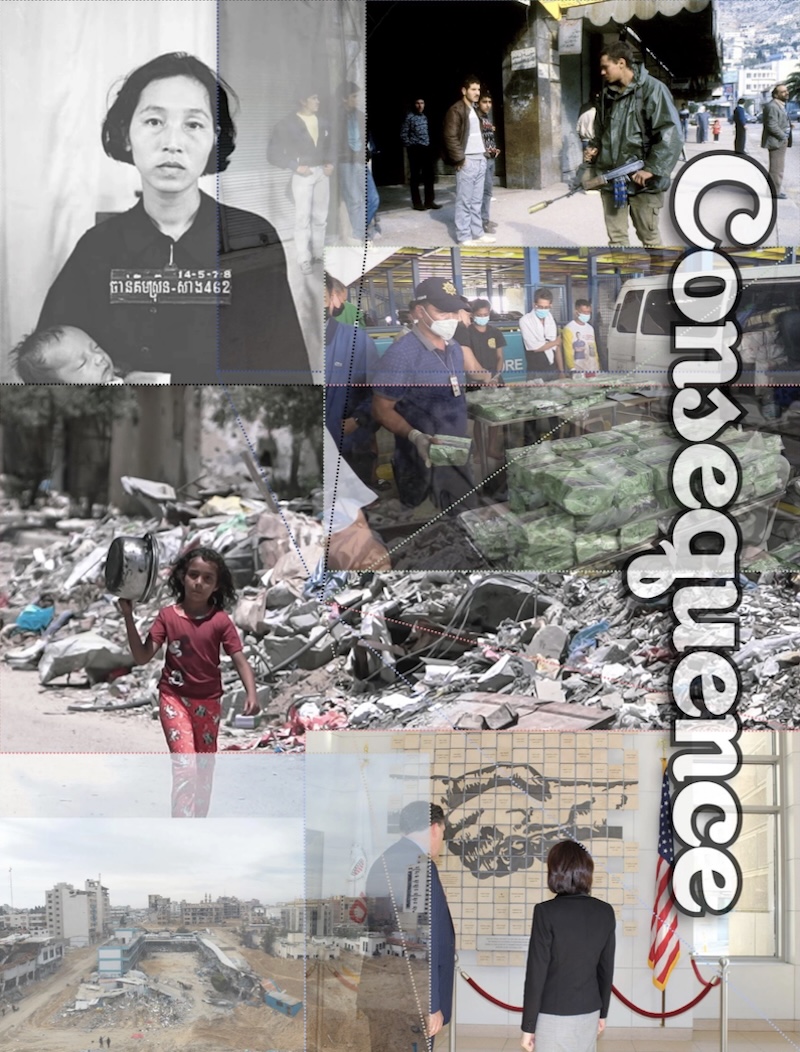

Consequence Forum is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit addressing the human consequences of war and geopolitical violence through literature, art, and community events. Since 2009, we’ve published fiction, poetry, nonfiction, translations, and visual art from combatants, victims, and witnesses worldwide—work that continues to earn recognition through anthologies and prizes. In a culture where war-making is obscured and its costs rendered invisible, we make them visible.

What is the Young Writers Nonfiction Project?

An annual mentorship initiative pairing emerging writers ages 15–24 with experienced editors to develop essays on war, trauma, and witness and publish them in digital e-magazine format. Our inaugural volume features writers from Gaza, Canada, the Philippines, and the United States—with some writing from active conflict zones.

How do I attend the January 31 reading?

The reading takes place online Jan. 31st at 6 PM EST. It’s free and open to the public. Please use the registration form on this page to receive the link.

Is Consequence Forum a magazine or an organization?

Both. Consequence is our biannual print journal and online publication. Consequence Forum is the 501(c)(3) nonprofit that publishes the magazine and also hosts readings, panels, workshops, and community programs like the Young Writers Nonfiction Project.

How can I support this work?

Donations directly fund programs like the Young Writers Nonfiction Project and ensure writers—including those in conflict zones—are compensated for their work. You can donate here or subscribe to Consequence journal.

The project was made possible by a grant from the Ellen Abbott Gilman Trust.