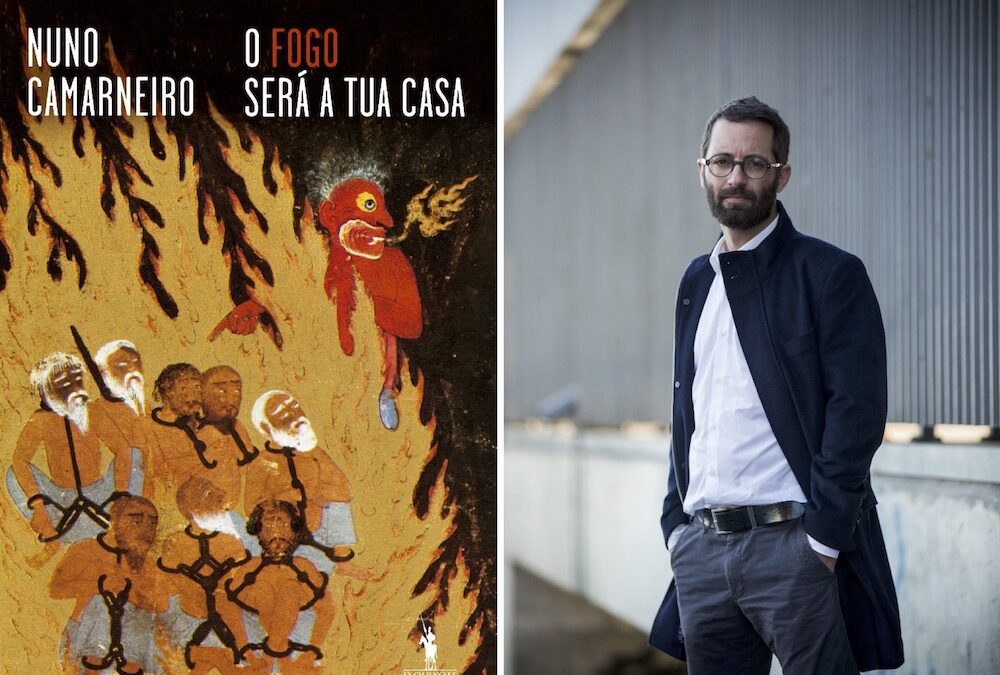

About the Novel: O Fogo Será a Tua Casa (Fire Shall Be Your Home) by Nuno Camarneiro was published in Portugal in 2018. It tells the story of an international group of hostages being held by rebels in an unnamed war-torn country in the Middle East and focuses on the day-to-day experiences of the main character—a Portuguese writer researching a project. Other captives include a Turkish journalist, a Belgian engineer, a Middle Eastern taxi driver, a Greek Orthodox nun, a US soldier, and a suicidal Frenchman. The hostages are being held for ransom, presumably to fund the rebel group’s activities, and each faces a different fate over the course of the novel. While the novel’s main storyline examines the idea of captivity in its most literal sense, the author employs flashbacks to moments in the lives of the characters before being kidnapped to consider how vices, excessive ambition, religious fundamentalism, and past trauma can create invisible prisons that, at times, may seem inescapable.

✺

If asked what I find most difficult about being in this prison, I wouldn’t know what to say. Whether it’d be the tense and violent moments, the moments of doubt, uncertainty, and fear, or the tedium that pervades every hour of the day.

We talk until we run out of things to say. We walk through the warehouse, we exercise—I agreed to only after they put me in confinement for not exercising—and we think a lot, invent games and competitions, and, otherwise, bore each other to death. Lying on the ground, not looking at anything, we wait and wait and wait.

I write, straining my eyes and hand so my handwriting takes up the least amount of space possible. I try to conserve my pad since I doubt they will give me another. I record the days and how each unfolds. I write letters that will never be sent, poems that are mediocre at best but important, and reflections that only make sense here. I think with the brain of an inmate who seeks to escape, imagining the outside world, remembering better days, making lists, lists of everything, of happy times, of all the people I’ve ever known, the places I’ve gone, all the movies I’ve seen. I think about what I need most, about what I hope to find again if I ever get out of here. I write:

I miss an actual bed. I miss going to bed late and finding it already warm, occupied by someone I want to smell and touch ever so gently so as not to wake her. I miss falling asleep completely absorbed in the sound of her breaths, combining with mine, becoming mine. I miss books, good ones, bad ones, and those in between. I miss reading before bed, reading while I eat alone, having last night’s dinner reheated in the microwave for lunch, reading in the bathtub, and reading a book while listening to the TV, not paying enough attention to either. I miss all children, those who scream and cry, those who are a nuisance, and those who laugh and wave goodbye with their little hands. I miss being with old friends, at one of those dinners or lunches I so often turn down thinking I can’t go, or I don’t have time, or the new novel, or whatever other lame excuse I come up with, but at which I have fun like when I was a child and didn’t have anything important to do. I miss not thinking about God. I believe a lot some days and barely at all others, with a scrupulously intermittent and irresponsible faith, accusing Him when necessary, thanking Him when I’m compelled to. I miss having an abstract God who doesn’t live on the other side of the world or speak a language so foreign to me. I miss the neighbors’ music coming through the walls, the sound of the neighbor above’s high heels, the vibrating pipes, the mailman who always chooses my bell—knowing full well I’ll miss him—the cars honking in the street because they’re carrying tired people inside, not letting me write in peace, the birds that sometimes sing, the dogs that also bark—poor dogs that bark—the stonemasons hammering away at the building next door, the older men and women who walk down the street and say in my window “ . . . he isn’t a drunk, he’s in AA . . . ,” and “I don’t want to change her, but I wish she were different . . . ,” conversations that come from behind and carry on to who knows where. I miss the men who drag their garbage cans out at 3:00 a.m. and say what they want because no one hears them, just me. I miss the neighbors who lock the front door and take a moment to complain about the weather and the Jehovah’s Witnesses who ask me if I’m scared of dying. I miss the wind and the falling rain; such a deep ache for the falling rain. I miss everything that irritates me and I later forget about. I miss Fridays at night, Saturdays in the morning, and Sundays in the afternoon. I miss nearly every day of the week.

Kerem interrupts my exercise and asks what I am writing. I tell him it’s not important. He laughs. “When a man senses death, he either feels like nothing matters or everything does. If he asks for paper and pencil, he’s not ready to die. You hungry?”

They barely fed us all day, so I’m grateful for the dates Kerem is offering. I take two, which I chew slowly so they last.

I distract myself from what I miss and accept Kerem’s gift and friendship. I know I’ll remember these moments if I survive. We are biased machines; we will always find some good in the bad and squirrel it away in our heads as precious material life cannot do without. Perhaps that is man’s greatest skill, to not see things exactly as they are but rather how we remember and feel them. We are clever creatures, but not so much so that we don’t fool ourselves when it’s in our interest.

We finish the dates Kerem had handed out to everyone and feel as if there is something religious about that act of sharing. We allow silence to fill the room but expect someone, or something, to break it.

Nuno Camarneiro (Author) / Michele Bantz (Translator)

Nuno Camarneiro was born in Figueira da Foz, Portugal, in 1977. He earned his undergraduate degree in Physical Engineering from the University of Coimbra and his PhD in Cultural Heritage Science from the University of Florence in Italy. Formerly a researcher in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Aveiro, he currently teaches in the School of Arts at the Catholic University of Porto and is a researcher at the Research Center for Science and Technology of the Arts. He is the author of No Meu Peito Não Cabem Pássaros (My Breast Can Hold No Birds) 2011 and Debaixo de Algum Céu (Under the Far Heavens) 2012 which won the LeYa Prize. In 2015, he published a collection of short stories entitled Se Eu Fosse Chão (If I Were Dust). He has also written three children’s books and has authored and co-authored multiple plays. His most recent novel, O Fogo Será a Tua Casa (Fire Shall Be Your Home), was published in 2018.

Michele Bantz is an American translator of Spanish and Portuguese. She attended the Middlebury Portuguese School as a Kathryn Davis Fellow for Peace and holds a BA in Hispanic Studies from Washington College and an MA in Translation from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. Her work as a literary translator has been awarded support in the form of funding, fellowships, and residencies from the American Literary Translators Association, Bread Loaf, The Granum Foundation, The Rona Jaffe Foundation, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She can be found at www.michelebantz.com.

Your blog is a constant source of inspiration for me. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and expertise. Your work makes a real difference!

Thanks, Ankara. Your comments are an inspiration to us.