*Translated into English by Peter Brown and Caroline Talpe. You can read Emmanuel’s original review in French here.

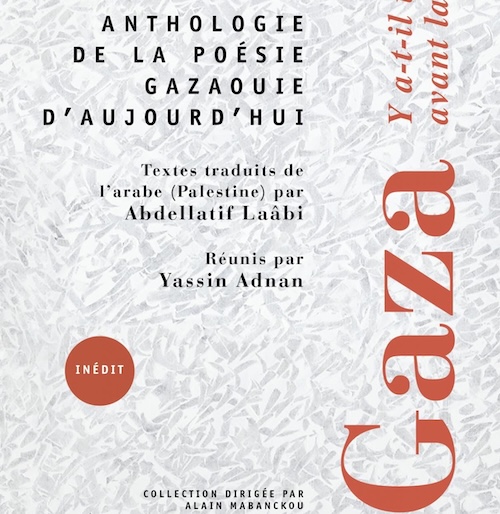

Gaza, Is There Life Before Death?

An anthology of poems, translated from Palestinian Arabic to French by Abdellatif Laâbi, collected by Yassin Adnan.

Editions Points, (France), 2025. 208 pages.

It’s a bit obscene to write commentary, to write criticism (even and maybe especially when such criticism is admiring) about a poem written at night, during the few seconds of silence before or after a bombardment with the expectation, unimaginable to those of us who haven’t lived it, of the end. It’s equally impossible to imagine a poem written by a woman who demands to search the rubble for her children, hoping to embrace at least one of them, knowing it’s pointless and forbidden:

Please let me see her

even only once!

—Alaa al-Qatraoui

At best, all I can say is how swept through I feel by the writings of the twenty-six poets in this anthology. Each utterance is like a cry. Although the words are very carefully rendered, they locate themselves outside of all conceptual discourse or intentional esthetic prioritization. They place themselves as close as possible to the wound. As close as possible to the wound, that is to say, to objectively locate themselves at the remains of a child, a woman, or an old man with words that cannot extract themselves from the horror:

I saw one body with a smashed head

another, scalped

I could see through the holes in his chest

the air passing between his bones

Each day a bone detaches from his rib cage

—Walid al-Akkad

Even if we have to acknowledge Apollinaire’s remarkable courage and lucidity during WWI (French poetry of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had little inclination to participate directly in war), his poems “at the front” were full of metaphor and lyricism. He took a semantic step back from the horror. There is no question of evasion in Gaza. On the contrary, this poetry is made of the simplest, most terrible realism, the clearest possible descriptions of the business of dismemberment as it’s carried out. This is poetry among the bones. It says what is, literally, without circumlocution:

The scraps of flesh flying in the air and a liver continuing to palpitate

—Shorouq Mohammed Doghmosh

With his maggots and his flesh

they presented him incomplete

with his broken bones

his mutilated skin

—Walid al-Akkad

Nothing, o Gaza, will permit the reconstruction of entire bodies

from scraps of flesh.

—Yahya Achour

Debris, remains, scraps, fragments, gashes: the bodies are split apart, reduced to waste, to nothing. And what’s most terrible, what’s most eloquent, is how these poems are not soaked in tears. The words are simply stated.

Upon reading the words, I’m forced to return to the question posed by Hölderlin: “What good are poets in times of suffering?”1 What is the value of a poem in the midst of war?

I can write a poem

with flowing blood […]

with human remains […]

with mutilated cadavers […]

I can write a poem

with naked silence

a declaration of powerlessness

What can a poem truly do?

—Yousef al-Qidra

Or again:

O my God

I don’t want to be a poet in wartime

—Hind Joudeh

The contents of this anthology oblige us to reconsider Hölderlin’s question from a new angle. It’s our incomprehension before the mind-boggling phenomena—horrific grief, hunger, thirst, relentless fear, bombs, stupefaction—and how someone manages to write a few coherent words, to affirm that I am still here. Or to record, in the midst of the kind of rudimentary survival formed by fear, that I am already no longer truly alive.

Being a poet privileged to live in a country at peace, I can’t imagine the strength (is it a matter of strength?) or the inconceivable courage required to write under such circumstances (but is it a question of courage? Aren’t I imposing two romanticized concepts on an activity I cannot possibly describe?). I can’t imagine because I’m not in a war, a condition which would absolutely put any question of writing poems, as well as my motivations that sustain such writing, in doubt. In effect, these texts leave poets living outside of Gaza without a voice. In Gaza, they know the likelihood of dying is greater than that of surviving and are pulling the string that weaves their existence together one last time, bringing them to the totality of what they’ve lived, what they hope for, how they hope to continue living:

Well, I’ll begin.

I am Noureddine Adnan Hajjaj, Palestinian writer. I’m twenty-seven and have many dreams […]. I refuse to accept the news that my life will go unnoticed, without you having said that this man loved life.

Hajjaj was killed by an IDF strike five days after writing his letter.

Here’s another:

My name is Adham al-Akkad

My father is a man who loves God very much.

These texts truly are poems. None of them represent a victory over fate or a final scene poignantly suggesting that “You can kill us, sure, but you cannot take away our souls,” something to represent a kind of victory of words over weapons and cruelty. This isn’t a story that ends well. To expect it might would be to assign these authors the kind of tearful compassion that we, as spectators, are no doubt bound to feel. They refuse, and a terrible sense of humor emerges:

I know all the victims of war

all the victims

even these five fingers here

I know who they belong to […]

I’m thinking about God

who created these limbs and assembled them

and I tell myself:

Now there’s an artistic genius

—Walid al-Akkad

Often, it’s anger that arises, the certainty that no one outside Gaza would ever hear about or understand their hell, that the rest of the world is only an impotent voyeur or an accomplice:

Good morning, Madness, o world!

What do you believe, since you just watch in silence,

purporting to understand everything?

—Hind Joudeh

Or:

We want nothing more from you

your booming voice

stops our cries from reaching the sky

We want nothing more from you

We simply want to die

in peace

—Husam Maarouf

The truest meaning, the inestimable value of these declarations, is that there is (or had been) someone there, an individual irreducibly alive in the world and this presence, however short, was true and nothing can put that presence in question, despite hatred, violence, or death. I think of Rilke’s poem:2

Everything once, only once.

Once and never again. And us as well

Once. Never again.

But this, having once been—even if it were only once—

To have been of this earth, that seems irrevocable.

Irrevocable. At last, despite enormous distress, facing the promise of imminent death, these poets affirm a vital persistence whose intensity of language is unequaled except by the fragility of its witnessing.

*

Yves Bonnefoy denounces all exterior transcendence in our world (it is striking to note that the poets in this anthology rarely refer to a divinity, whether to beg him to act, to rely upon such action, or to deny that he has any power). For Bonnefoy—for him it’s obvious—no discourse comes close to capturing the shifting complexity of even the least object. Everything, here below, is subject to time, which condemns any effort at adequate or enduring definition. Language always falls short of a full, transitory experience of reality. These Palestinians confirm this poetic deficiency; nothing can really be said about their suffering, no words could approach the horror of their situation. The intentional, coordinated, rationalized violence has its distinct objective reality and that violence torments the other real objects: human beings dismembered by bombs, homes demolished, farms and crops methodically destroyed. How would these Gazans be able to understand and recognize from now on what constitutes their reason for continuing to live, to recognize what is, moment by moment, being disfigured for all time. This kind of violence represents the ultimate degree of reality, a reality that imposes itself through such intense, brutal, and cruel events that nothing can be said that would correspond to it. At this level of intensity, speech itself is stunned:

This war is not a

This one

This one

(I don’t the find the suitable word)

—Shorouq Mohammed Doghmosh

Or:

We can hear nothing more, the rain and me, since together we’ve

discovered that the sky has no defining face

that the earth is capable of observing total silence to the last day of its

existence and the existence of the universe in its entirety

—Ashraf Fayad

In his book, Le siècle ou la parole a été victime3 [The Century in Which Language Was a Victim], Bonnefoy analyzes the distinguishing feature of Nazi willpower during WWII: the inversion of values through the corruption of language in Germany (Arbeit macht frei) and the eradication, through objectification of human beings in extermination camps, of any further possibility of imagining hope: “[…] it’s clear it wasn’t only a matter of killing, either quickly or slowly, but to push the prisoners to stop believing—before their deaths—in the prospect of political representation, in values, in the memories which, whatever they were, would otherwise have made it inconceivable for them to snatch a morsel of food from a starving loved one.” This same intention is at work in Gaza, to banish all hope before death. In the accumulation of ruins, through the disappearance through bombardment of all concrete realization of human community (the determined destruction of cultivated fields, water supplies, energy sources, where food-distribution points become shooting ranges and lotteries of death, where any prospect of joy or empathy is transformed to hatred and stupefaction for generations to come). In Gaza, we are witnessing an abominable “ethnic cleansing” at least, although that expression, for its suggestion of displacement and deportation, would only be a euphemism for an ongoing genocide during which the displaced are condemned to move from one refugee camp to another within their own country):

As for us

we must

give up our lives

to gain a country

just to get buried there.

—Ashraf Fayad

But Bonnefoy also observed that Nazism “did not triumph,” since “as much as through the body of its practices, a culture in persecution can hold its own against an enemy through an incessantly critical, living language in search of truth.” For the Jews in the camps, “the most bloodless speech gave no consent to its dismissal.” Not that they were rescued from death, but their own sense of language remained intact even in the worst quarters of the camps, even in awaiting death. Robert Antelme and Primo Levi recounted that, come what may, the inmates continued to recite poetry in Auschwitz, so that “the demonic would not enter the house of meaning.”4

This is what is happening in Gaza, where despite death, the meaning of words, of language above all, that which speaks of humanity, hasn’t disappeared. It’s there, at the point of writing that it’s no longer possible to have faith in humanity, where we must claim our humanity:

My tomb will be the open air and my headstone a cloud in whose shade the children will grow. They haven’t cut off the air, o God […]. I am not free if I cannot choose my death. It’s only at the moment of death that I’ll be free. So, go on! Destroy me even more, dynamite even more, and dig up more of the earth to welcome the dead.

—Haydar al-Ghazali

This is a poem, since poetry is the first and the last word. Thanks to poetry language is not lost. If what is taking place defies language and prevents all adequate transcription, the words will however have been uttered. “Unspeakable” doesn’t mean one cannot speak. In Images malgré tout [Images in Spite of Everything], Georges Didi-Hoberman presents four photos taken by a member of the Sonderkommando in 1944 Auschwitz. “They are,” Didi-Hoberman writes, “for us—for our eyes today—the truth itself, to know what remains of it, its poor rags: this is what remains, visually, of Auschwitz.”5

These images and these Palestinian verses are the true witnessing of a genocidal reality and must not be dismissed as fragmentary or imperfect in comparison with standards observable in times of peace and comfort. “In order to know, we must imagine,” says Didi-Hoberman. In the same way, Imre Kertész explains that “only the esthetic imagination allows us to conceive an idea of what the Holocaust was.”6 We have to acknowledge that this Gazan poetry invites us to “imagine” in this way through language (though it remains impossible for us to understand) and however they might fail, however terribly honest and true they might be, they must not be inaccessible to us, to remain in a kind of black hole.

It’s wrong to say that “writing poetry after Auschwitz would be barbaric,” as Theodore Adorno asserted7, even if we understand why he said it, even if, years later, he himself wrote that, in the end, it was in fact possible to write poems.8 And it’s not true that we cannot write poetry after Gaza. Kertész corrected the record, affirming that from now on we cannot write poetry but “after” Auschwitz. In my case, I have to understand that I can only write poetry “after” Gaza because, there, in Gaza, human beings lived and continue to live. The poems in this book tell us that these people have been present in the world.

*

I began to write this on October 13, 2025, as I saw the retransmission of speeches by Netanyahu and Trump to the Knesset on BFMTV, the continuous news channel here in France. Twenty Israelis and 1,950 Palestinian prisoners had been released. In an address made knowing he was supported by the most powerful man on earth, Netanyahu gave thanks to Trump for his intervention but carefully omitted mentioning the tens of thousands of deaths caused by the IDF. Trump’s speech, as always, was frightfully erratic, full of self-satisfaction, combining remarks about peace, his family, and the glorious quality of American weapons. Confident he could say whatever nonsense came to mind, he had the gall to ask the president of the Knesset to extend amnesty to the Israeli prime minister.

We know that nothing with respect to the Palestinian question will be resolved as long as the Palestinians have no real participation in the larger negotiations. Nothing will be resolved as long as the Palestinians have no legitimate representation and are absent from the talks. In the meantime, their humanity is being continually denied. Gaza remains a concentration camp under an open sky.

As for what remains? A gesture, the kind of written witnessing the poet Rifaat al-Aareer composes with a gasp, with a breath:

If I must die

It means that you

You have to live

To tell my story

A short time later al-Aareer, along with his family, died during a bombardment.

~

1. Friedrich Hölderlin, “Bread and Wine,” 1800.

2. Rainer Maria Rilke, “Ninth Duino Elegie,” 1923.

3. Yves Bonnefoy, Le siècle où la parole a été victim (Mercure de France, 2010).

4. Ibidem.

5. Georges Didi-Huberman, Images malgré tout (Éditions de Minuit, 2004).

6. Imre Kertész, L’Holocauste comme culture (Actes Sud, 2009).

7. Théodor Adorno, Prismen (Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft, 1955).

8. Théodor Adorno, Negative Dialektik (Suhrkamp Verlag, 1966).

Emmanuel Merle

Emmanuel Merle was born in 1958 in Grenoble, France. He has published around thirty books of poetry with various publishing houses (Gallimard, Voix d’encre, L’Escampette, La Passe du vent, Jacques André éditeur, La Rumeur libre, among others). He regularly collaborates with visual artists on artist’s books. He translates American poets from English (United States). Finally, he is president of the cultural association L’Espace Pandora (Vénissieux). Some of his titles include: Redwood, Amère Indienne, Un homme à la mer (Gallimard), Ici en exil, Dernières paroles de Perceval (L’Escampette), Pierres de folie (La Passe du Vent), Le Chien de Goya, Les mots du peintre (Encre et Lumière), Démembrements, Habiter l’arbre (Voix d’Encre), Schiste, Tourbe, Anthracite (Alidades), Avoir lieu (L’Etoile des limites), Leurs langues sont des cendres (La Crypte), Brasiers (La Rumeur libre). A collection of his poems, Elsewhere On Earth (Guernica), translated by Peter Brown, appeared in English in 2014.