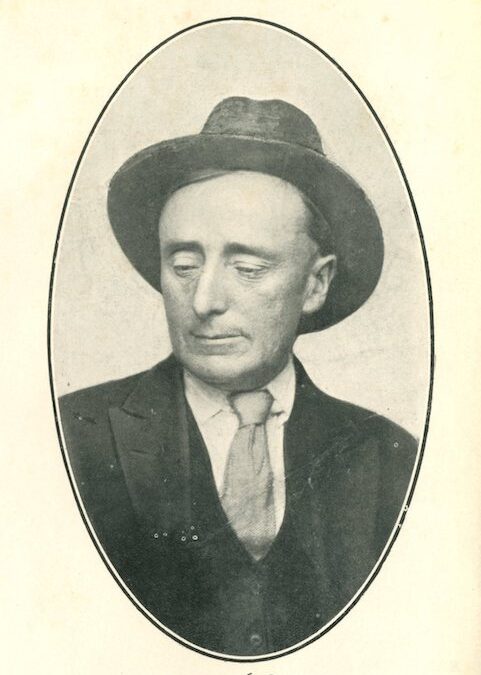

Pádraic Ó Conaire (1882-1928), a pioneering Modernist author with a bilingual mind and comic wit

(photo courtesy Galway City Museum, Ireland)

Pádraic Ó Conaire’s Enduring Art of Conflict Narration

It is a foggy day in March 1916, and British Resident Magistrate Robert Sparrow can’t quite believe why he’s been pulled from Londonderry to oversee a special court, in the seaside village of Rathmullan. Nestled on Lough Swilly, a meandering waterway poking into the North Atlantic in Ireland’s County Donegal, the tranquil spot is a world away from the Western Front. Yet the judge knows that the Great War is everywhere simmering, and that the British military and media fear the contagion might spread here, too.

“Who’s this defendant, Pádraic Ó Conaire?” the judge says, turning to Justice of the Peace John Deeny.

“He told the arresting officer,” recounts Deeny, surveying the unimpressive defendant, scraggly and hunched in a threadbare coat, “that he’s a journalist—”

“And I’m King George!” scoffs Magistrate Sparrow. “He’s a Fenian rascal and a spy—perhaps, one of those so-called ‘Irish Volunteers.’ We’ll be finished by lunchtime.”

Magistrate Sparrow begins his formulaic recitations, but is soon annoyed. When called, defendant Ó Conaire meekly gives a statement—in the Irish language. His solicitor sighs, then confers with Magistrate Sparrow. The Irish language is barely spoken (excepting a new fad among nationalists), and is relegated to a few rural enclaves. Centuries of British colonization have largely succeeded in modernizing the country—though some, like this bewildering defendant, disrespect all this progress, Sparrow thinks.

“Order!” the judge barks, striking his gavel as angry voices echo in the background. “I say—you are speaking to a British magistrate, Mr. Ó Conaire! Despite your manner of dress, I know you’re quite capable of speaking the King’s English—after all, these records attest you’ve been a civil servant in London—albeit of minor rank, from 1900 on.”

The defendant whispers to his solicitor, who stands and bravely speaks on the amused-looking Ó Conaire’s behalf. “Your Honor, my client says that finding himself presently in Ireland, and being Irish, he considers it sensible to speak the Irish language, though he wouldn’t wish it upon you—that is his observation.”

“His observation,” retorts Magistrate Sparrow, flipping the papers before him, “was of the coastal defenses—that’s what Royal Irish Constabulary Acting Sergeant Brady reported. What has Mr. Ó Conaire to say?”

The defendant whispers again to his lawyer who, red-faced, speaks. “Your Honor, my client cannot properly understand you, and wonders that it might not be impossible to find, from among our RIC, even one good man to provide translation into Irish.”

A small uproar ensues, but Magistrate Sparrow wants this matter finished quickly, lest it become protracted and wind up in the newspapers. A short search turns into a two-hour delay, however, until finally a single Irish-speaking RIC officer cane be dragged in from the Atlantic drizzle.

“Now—the arresting officer also discovered the defendant making suspicious sketches,” Sparrow continues, his new translator relaying these understood words into Irish for Ó Conaire’s amusement, compounding the trial’s ridiculousness. “Therefore, RIC District Inspector Reagan remanded you into custody, for having violated the Defence of the Realm Act—a most serious offense.”

Again, whispers between the defendant and his solicitor, Ó Conaire stands, speaking Irish. The dubious RIC translator-office carries on.

“Your Honor, Mr. Ó Conaire says he was merely touring Ulster to check on the health of the Irish language,” the RIC translator-officer states, swallowing his throat. “He says he isn’t to blame if the British Empire has introduced buildings and even Acts of such magnificence, that the Irish language may presently lack sufficient words to describe them, so long has it been neglected.”

Waves of tension ripple around the courtroom. Magistrate Sparrow ponders the pluck of this quixotic, bedraggled man. Clearly, he decides, Pádraic Ó Conaire is more an eccentric than one of those ‘wild Irish’ militant-types about which the authorities and newspapers have been warning.

“Sir,” wheezes the exasperated magistrate, “you should have simply answered that RIC officer in English, like a good man. You’d not be in your current predicament, had you not persisted in the farce of speaking in Irish.”

The RIC officer again translates the judge’s words to humor the smiling defendant, prolonging the surreal game of brinksmanship. Ó Conaire whispers to his solicitor, who stands and answers again in Irish. The disbelieving RIC officer dutifully translates for Magistrate Sparrow.

“Your Honor—he says he prays for your health,” translates the officer. “And that you will live long enough to see this very farce realized—for Mr. Ó Conaire thinks it will not be many years more, before Irish becomes official language of a free and independent Ireland!”

Amidst the uproar of protest, a tinny gavel rings out, seeking order.

*

This scene is how I imagine the real spring 1916 special court appearance of Pádraic Ó Conaire (Patrick Conroy, 1882-1928) might have gone. Indeed, the Irish-language Modernist writer was detained while touring the Gaeltachtaí (Irish-speaking areas) of Ulster, for the Gaelic League—the culture-oriented nationalist group that also paid for his lawyer in Donegal. Since 1915, when he’d left his wife and children in London, fearing conscription by the British Army, the writer had also become elevated to the League’s Executive Committee.

While Ó Conaire’s focus was always primarily linguistic, this participation brought him close to the revolutionary scene that would soon unfold in the confusing and chaotic Easter Rising, which occurred on Easter Monday, the 24th of April 1916, in Dublin.

Yet while the Donegal incident was certainly dangerous, it was fortunate for Ó Conaire, as he was still detained when the would-be revolutionaries briefly occupied Dublin’s General Post Office, before surrendering to British troops. Never a part of the secret military operations leading to the Rising, Ó Conaire would nevertheless immortalize it the following year, in a collection of Irish-language short stories. Importantly, his comic and broad-minded work, written in simple and straightforward prose, helped ordinary people come to terms with loss, while limiting tendencies to mythologize complex conflict events.

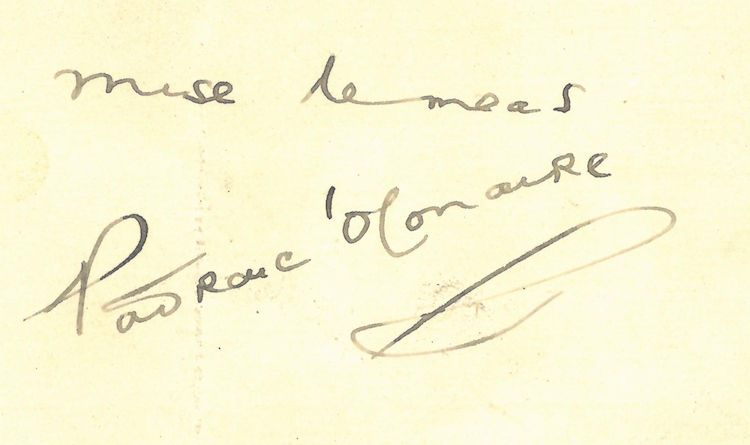

The preserved signature of Pádraic Ó Conaire (photo courtesy Galway City Museum, Ireland)

The preserved signature of Pádraic Ó Conaire (photo courtesy Galway City Museum, Ireland)

As the example of Pádraic Ó Conaire reveals, writers play vital roles as witnesses to war, and also in transforming collective consciousness and memory of conflict. Responsibility comes with this role. Writers’ specific narrative choices give them the power of influencing how individuals and whole populations internalize and respond to conflict; thus, writers play a vital role in how people understand and orient themselves to war, both in the moment and long after it. Often, writers amplify tendencies toward further violence, or immortalize semi-mythological narratives about combatants. In happier cases, writers who are both brave and principled can, however, recast conflict in a more honest light that defuses future tensions while soothing collective traumas, and advancing an honest narrative.

Pádraic Ó Conaire achieved this, and without diminishing the human cost of war. Rather, he used the art of narrative to establish something new and vital that honors both witnesses of war and those caught up in a confusing conflict—one that was even cancelled and forced through by its organizers, after the British intercepted a maritime arms shipment from Germany before Easter and were planning to arrest revolutionary leaders, whether or not they rebelled. In complex conflict situations that lack clear moral definition, this can also necessitates unique writing methods. Such conceptions emphasize the difficulty of ever ascertaining the full facts of a reality obscured by the “fog of war.” Here, Ó Conaire’s subtle storytelling itself exemplifies this aporetic concept.

A significant Irish-language writer, journalist and teacher, Ó Conaire believed in the Irish language’s expansion despite its political suppression and general disuse. However, he informed his Irish-language prose with international literary influences, making him among the first and best Modernist writers in Irish. This double-influence is explained by his dual life experience. Born in Galway on Ireland’s west coast, he was orphaned in 1893 and partly raised by relatives in a Gaeltacht village in nearby Connemara, a bleakly beautiful stretch of coastal bogs known for its peat, local firewater, and Irish-language tradition of folk stories. The young man was influenced by the people, stories, and nature of his native region, taking it with him to college in Dublin. Although he did not graduate, he was classmates there with Éamon de Valera, the future leader of an independent Ireland. (De Valera would also inaugurate Ó Conaire’s statue on Galway’s Eyre Square in 1935.)

Ó Conaire’s second influence—international Modernist literature—was furthered from 1900 in London, where he indeed worked as a minor British civil servant, like many others fleeing Ireland’s crushing poverty. Ó Conaire also joined the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge), which promoted the Irish language, and so began his publishing career. He wrote for the League’s newspaper, An Claidheamh Soluis (The Sword of Light), and his Irish-language fiction benefited from his insightful bilingual worldview. Ó Conaire employed a Realist style to explore the difficulties of life for Irish émigrés. Here, his major success was the 1910 novel Deoraíocht (Exile), which chronicled the harsh realities of urban poverty, in simple prose that avoided any temptation to romanticize Irish rural life (a fault for which other authors and playwrights of the Irish Literary Revival were and are criticized). The transplanted Galwegian thus inhabited an English-speaking environment, while bringing international influences into a new literature in an old language (Irish)—one having few actual writers, and less books in print. There was little literary market, and Irish-language knowledge did not enhance economic prospects even in Ireland, where less than one percent of people still spoke their ancestral tongue.

In London, Ó Conaire also had four children with common-law wife Mary McManus, who he would marry much later. After the First World War brought the threat of British conscription, Ó Conaire was sent to Ireland in 1915. Wartime England was, anyway, a more dangerous place for those associated with secret groups like the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood (IR), which had agreed one month after Britain’s August 1914 war declaration on Germany to launch an uprising. Ó Conaire was no fighter, and his presence in Ireland with the Gaelic League was instead for assessing the Irish language’s condition, teaching, and political activism.

The flammable events that would lead to both the author’s great short-story collection, and the 1916 Easter Rising had converged, partly due to a political conflict resolution statement, one exacerbated by Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination the summer previous. Since the 1870s, the political issue of “Home Rule” for Ireland had been championed by the Irish political party that sought a political solution to the colonial occupation short of independence. In the years just before the Great War, this issue had made the British government coalition unstable, with the House of Lords vetoing the third attempt at passing the Home Rule bill since its failed introduction in 1886. In opposing Home Rule, four hundred and fifty thousand Protestants in Ulster signed a “covenant” to resist in November 1912; soon after, a loyalist militia, the Ulster Volunteers, was created. In reaction, the pro-independence Irish Volunteers was formed in 1913 by Catholic nationalists. By the time the Lords’ obstructionism was overcome, war broke out in Europe—forcing Home Rule’s suspension, angering both moderates and nationalists demanding full independence.

On August 6, 1914, two days after declaring war against Germany, British Liberal Party Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith justified the decision to support Belgium in a parliamentary speech containing this line: “ . . . we are fighting to vindicate the principle that small nationalities are not to be crushed, in defiance of international good faith, by the arbitrary will of a strong and overmastering Power.” To Irish nationalists, this argumentation was hypocritical, as Ireland too was a “small nation,” but one mistreated by British colonial rule. More galling, though, was the subservient support for this pro-war position from the Irish governing coalition party leader in London, John Redmond of the Irish Parliamentary Party. Redmond supported the war and the “small nationalities” rhetoric, encouraging Irishmen to volunteer for the British military.

This could be dismissed as base politics, except that Redmond and his older brother, Willie (a parliamentarian who would die in battle for the British Army) seem to have sincerely believed in their martial rhetoric. Their argument was that the German “common enemy” would, after an inevitable final victory, transform the surviving Irish combatants into a unified domestic population. They argued this would prevent any future partition of Ireland. This was not to be, of course, though thousands of Irishmen did indeed volunteer for the British army—some for adventure, others for economic gain, and others for the cause.

After war’s outbreak, the organization that Pádraic Ó Conaire also secretly joined in London (the Irish Volunteers, forerunners of the Irish Republican Army) began preparations for the disastrous Easter Rising, in which Dublin was partly burned. Afterwards, the British executed sixteen of the Rising’s leaders and took thousands of political prisoners. The revolt had been presciently foretold by one of its ill-fated leaders, Patrick Pearse, in a November 8, 1913 article entitled “The Coming Revolution.” Published in the Gaelic League’s newspaper, Pearse’s theologically and nationalistically charged argument claims that while the Gaelic League had provided a good educative basis for future action, it was now “a spent force,” and its generation of leaders must yield to the next generation, for the common good, in undertaking ominous and unpredictable actions for the nation. Pease concludes by crediting the Protestant loyalists for setting an example; though he nowhere mentions the word, his rhetorical call for mass arming invites a tendency towards anarchy. Pearse writes:

I am glad, then, that the North has “begun.” I am glad that the Orangemen have armed, for it is a goodly thing to see arms in Irish hands. I should like to see the AOH armed. I should like to see the Transport Workers armed. I should like to see any and every body of Irish citizens armed. We must accustom ourselves to the thought of arms, to the sight of arms, to the use of arms. We may make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people; but bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing, and the nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood. There are many things more horrible than bloodshed; and slavery is one of them.

While Pádraic Ó Conaire himself never struck a symbolic blow against empire with the ill-fated volunteers, his arrest in Ulster documented above did reach the media, adding to his celebrity and the general cause of the Irish language. The very idea of an uprising was controversial among nationalists and moderates, as it seemed so unlikely to succeed—a certain suicide, many argued. Despite the IRB’s obsession with secrecy, they gave inadequate consideration to the risk that by seeking German aid, they would become vulnerable to leaks from the Germany side—as indeed happened, when the Royal Navy intercepted a message warning of the planned arms shipment to County Kerry in April 1916. The Rising had failed before it ever began.

A reasoned reaction to these conflict events came with Ó Conaire’s most intriguing work. He retold the Rising through seven peripheral stories, which present the strange tales of seven persons involved somehow in it, remarkably blending fact and fiction. Titled Seacht mBua an Éirí Amach (Seven Virtues of the Rising), it was immediately successful when published in 1917, but was not translated into English until the 1980s. Translated fully only in 2016, it is now available in a bilingual edition from Dublin’s Arlen House (with an identical US edition by Syracuse University Press). Readers today can thus understand, with the proper context, the great vision this now-obscure author actually achieved in responding to his country’s most controversial and tragic conflict event of that era. Here, Ó Conaire made a literary statement and fictional creation that would live on its own terms, as a story with universal application and relevance to the human condition generally.

While readers can enjoy these stories without context, even a little background adds significantly to understanding the stories as readers of 1917 Ireland would have. The story to be examined below, for example, alludes to a specific historical personality who is relevant to the above-cited conflict events. This personality was one of the few Irish clerics who criticized the Great War. Limerick’s Catholic Bishop, Edward O’Dwyer (1842-1917) supported Pope Benedict XV’s peace plea, and criticized John Redmond’s pro-war policy in newspapers. O’Dwyer opposed London’s suspension of Home Rule, warning correctly about a future partition. Historian Jérôme Aan de Wiel notes that O’Dwyer denounced the war “at every possible opportunity,” attacking Redmond’s call for Irish volunteers in the British military. Indeed, as the war worsened and Irish nationalist hopes remained unfulfilled, O’Dwyer “became the country’s most popular ecclesiastic.”

O’Dwyer’s pacifistic rhetoric would earn him a place both in the public and as one of the major characters in Seven Virtues of the Rising. For among the many complex moving parts of the local and world conflicts of the time was the reassignment of British General John Maxwell (1859-1929) to Dublin from Egypt. There, Maxwell had been relatively successful and capable (as is indicated in the war memoir of one Irishman in the British forces, Lewen Weldon’s 1926 Hard Lying). Reaching Dublin on April 28, 1916, General Maxwell arrived in time to take the surrender of Irish rebels. However, his reaction to the contained chaos resembled more the thinking of the conventional war from which he had come. Far from the multi-spectrum battlefield of the desert and Eastern Mediterranean, Maxwell was now in a congested, generally peaceful urban environment. In Dublin, the extraordinary war powers passed on August 8, 1914, by the British government (in relation to the World War) were now ripe for abuse by emergency military governance. Ironically, this heavy-handed reaction did more to advance Irish independence than anything the nationalists could ever have done.

General Maxwell’s controversial post-conflict actions thus fed future conflict. In hindsight, it was predictable conduct from a military officer emerging from a conventional war zone, ill-equipped to moderate his mandate to local realities. And, since the Royal Navy had just intercepted the German arms ship (disguised as a Norwegian fishing trawler), they doubtless feared another could be on its way. Paranoia was in the air, and the quick trials of revolutionaries like Patrick Pearse were (as a later Crown inquiry found) illegal, lacking defense lawyers. Maxwell arrested anyone possibly linked to the short-lasting and underwhelming Rising (over thirty-four hundred men and seventy-eight women). The highest-profile rebels were executed in a staggered fashion that sustained tensions and a simmering anti-British public sentiment.

Thus, even though the Rising had lacked mass participation or appeal, General Maxwell’s handling of it created more sympathy for the nationalists and their Sinn Féin party. This led to a landslide vote for the pro-independence party in 1917 by-elections, damaging Redmond’s IPP and his claim to speak politically for the Irish nation. Home Rule became untenable, almost guaranteeing a guerrilla war for independence, as would indeed occur under the Irish Republican Army of Michael Collins and de Valera, six years later.

The dramatic introduction of Bishop O’Dwyer nationally came with his letter to General Maxwell, who had pressured the fiery prelate into disciplining nationalist priests. O’Dwyer’s May 17, 1916 reply denigrated Maxwell as the “military dictator of Ireland,” Bishop O’Dwyer refused the general’s order, and criticized Maxwell’s suppression of the Rising as “wantonly cruel and oppressive,” citing the execution of surrendered revolutionaries and prisoner deportations. The bishop denounces Maxwell’s “regime” as “one of the worst and blackest chapters in the history of the misgovernment of this country.”

Given such rhetoric, one might assume that an Irish nationalist writer seeking to recast these conflict events would seize on the dramatic. Ó Conaire, however, took a different approach, one in keeping with the tragicomic and morally informed nature of his fictional exercise. In the collection’s relevant chapter, “The Bishop’s Soul” (“Anam An Easpaig”), he writes a comedic story-within-a-story, following the structure of an American author popular shortly before, O. Henry (William Sydney Porter, 1862-1910). He builds out from the concept of an unnamed (but nationally known) bishop who is inwardly timid, troubled by the difficult decision he must make: about whether to discipline a certain Fr. O’Donnell, for this young priest’s nationalism. The bishop is torn because, while somewhat hot-headed, the young priest seems essentially good and well-meaning. Still, the bishop considers the nationalist goal of independence an oft-tried and failed proposition; he considers his own stable life and good relations with high officials, which seem preferable.

Unlike the historical reality of Bishop O’Dwyer, the story is narrated on the night of the burning of Dublin, with the Rising not mentioned until near story’s end. Also, its fictional setting has nothing to do with the historical bishop’s movements on that night. Nevertheless, as the story evolves, it becomes clear that the author is gently lampooning Bishop O’Dwyer, by constructing a narrative that counters an alter-ego of courageous outspokenness. In the privacy of the fictional bishop’s mind, Ó Conaire creates a space for comic juxtapositions and a moral resolution, in which the bishop eventually discovers his courage through a transformative experience that takes him outside of his comfort zone, and finally, makes him a witness to conflict.

*

The story begins with a humorous sentence with dual meanings: “The bishop was asleep.” The story’s early part sees the bishop become separated from his driver in a rural area twenty miles from Dublin: while the cursing driver is laboring under the car to repair it, the bishop wanders off to keep warm, dressed not in his clerical garb but in an overcoat, weighing his moral dilemma about the young priest. At the same time, the driver fixes the car and leaves. He assumes, wrongly, that the bishop is still asleep in the back.

From this first comic misunderstanding, a cavalcade of others follows at regular intervals. Ó Conaire’s narrator chronicles two simultaneous stories. The first concerns the panicked driver, who searches for the bishop, but finds only a random Englishman, recently arrived in Ireland; the two have several comic misunderstandings, and end up getting thrown out of a country pub. The second story concerns the bishop, who eventually finds this pub, the only sign of civilization. Still timid in his coat, the bishop is unaware of his driver’s recent misadventures.

The concept of misrecognition is key to the storytelling here. Since the lost bishop is wearing an overcoat and cannot be recognized as a cleric when reaching the pub—a place he should never be at any hour, let alone after legal hours—he has to introduce himself carefully, and consider how to ‘be himself’ in front of the locals. His customary public image as a moral authority exists within a carefully organized social hierarchy and is now temporarily gone. But this new reality also means that, unrecognized by his flock, the bishop can for once actually see the regular people as they are, when not pretending on their part to pay obeisance to a famous religious figure. In this manner, Ó Conaire’s story subtly demonstrates that both the bishop and his parishioners are accustomed to playing fictitious roles to each other in daily life.

When the bishop attempts to enter the after-hours country pub, the suspicious locals peering through the keyhole fear that the shadowy “man in black” is from the Royal Irish Constabulary, accentuating the comedy of misperceptions. When the bishop tries again, they again misunderstand him after an identification request is met only by a timid voice: “‘It’s me,’ said the bishop shyly; and he said it so meekly anyone would think it was a man looking for drink out of hours.” Now mistaking the bishop for an earlier customer who had not paid, the pub’s landlady angrily tells him to go away, if he won’t clear his “slate.” Confused, the bishop wanders off, but returns when frightened by a dog, his inner courage still missing. Fright causes him to knock again, but in a certain way that is mistaken for the “secret knock” customary to an after-hours patron. The bishop is finally let in, hoping to learn whether anyone has seen his driver—while not disclosing his identity as a bishop, which makes things rather harder.

The bishop is again confused when asked if his driver was English, as an Englishman and “his friend” had been there. Failing to understand, he says no. He also declines the landlady’s offer of whiskey—instead, meekly requesting “hot milk.” This after-hours absurdity convinces the pub crowd that their strange guest must be already drunk. By the time the bishop gets his hot milk, he is under suspicion of involvement with the Englishman, who (in the pub’s overheard conversation) had mentioned looking for a bishop who’d abandoned his wife. The point refers to a similarly misunderstood conversation between the Englishman and the driver earlier, and the bishop and pub-goers alike remain comically ignorant of each other, or the events that have happened. This is a very effective, if peripheral, choice of narrative tactics around conflict situations.

The surreal comedy is only ended by more improbable news; the Rising is underway. Ironically, this actually liberates the bishop from the measured scrutiny of the pub crowd. A local enters, and the crowd follows him out to see a distant Dublin ablaze. The disbelieving bishop, who had been sequestered in a monastery for days and thus knows nothing, wanders out to join the others on a hill. In this scene, the bishop also finds his driver, injured from fighting the Englishman. The narrator describes the view of Dublin ablaze thus:

An amazing sight lay before the bishop then. Away off in the lowlands he could see a great fire. Flames leaped up from it, reddening the clouds. There was a large crowd around him; each man seemed to hold a secret . . .

A loud explosion was heard. Many took fright. All were too moved to speak . . .

Another tremendous explosion!

Something gave way in the bishop’s heart. His innermost being was filled with a great light. If Father O’Donnell was here now…

Two explosions, one after the other!

A youth by his side, his eyes shining in a way seldom seen, pressed the bishop’s hand to his own.

“If only we had guns . . .” said the youth.

“If only . . .” said the bishop, and he bowed his head.

This passage implies a mentioned early in the story of the young priest and the ‘sword of light’ motif, which is also an Irish-language play on words for the name of the Gaelic League’s newspaper. And since that newspaper also published Patrick Pearse’s famous 1913 call to arms mentioned above, it is quite possible that the author is here alluding to that too, in the youth’s comments about “if only we had guns.” Thus, Ó Conaire subtly demonstrates Pearse’s actual 1913 call for a generational shift, as if it was something destined in the national consciousness. And yet, he does not promote actual conflict, for the story is about the bishop’s inner dilemma.

*

This conflict-witness experience does, however, successfully steel the bishop’s soul. In the final (or, second ending), he summons Fr. O’Donnell to his office and reveals both the letter from the army requesting him to be disciplined, and the letter he will actually send. The priest’s teary and thankful reaction indicates that the bishop has decided to defy the military’s pressure and support the young priest. At story’s end, the narrator continues, the bishop tells the young priest his own version of the amusing story of his own misadventure just narrated.

“The Bishop’s Soul” is just one of the seven narratives of Ó Conaire’s Seven Virtues of the Rising. Of course, context enables the fuller enjoyment of these conflict narratives, though they do stand alone and are very readable without it. The brilliance of Ó Conaire lies in his succinct and playful prose, in which he imagines stories both entertaining and deeply moving.

Over a century removed from the conflict to which they ref, stories like “The Bishop’s Soul” may seem just vignettes of wars past. But in Ó Conaire’s own time they were significant for a nation in grief and confusion, seeking to process the chaotic events of spring 1916, as the country lurched toward open war. Given the situation’s flammable nature, Ó Conaire was careful not to write in a manner that would inflame tensions, or endanger himself in Ireland, or his family in England. He even made sure to delay publication until the Rising’s last political prisoners were released.

Pádraic Ó Conaire’s example as a witness to conflict thus remains useful to writers, both for these decisions and for his storytelling tactics, which repay repeated reading. His wit (involving puns and jokes in Irish) add meaning, and his style and structure reveal a professional author, informed by diverse international literary influences. In these pages, his irrepressible comic spirit shines through. Today, Ó Conaire remains an undiscovered master, whose ability to capture the effect of conflict on ordinary and extraordinary people remains of great merit to readers and writers alike.

Irish President Éamon de Valera presides over the Ó Conaire statue unveiling in Galway’s Eyre Square, on Easter Satirday pf 1935 (photo courtesy Galway City Museum, Ireland)

Irish President Éamon de Valera presides over the Ó Conaire statue unveiling in Galway’s Eyre Square, on Easter Satirday pf 1935 (photo courtesy Galway City Museum, Ireland)

Chris Deliso

New England native Chris Deliso is a professional writer who spent twenty-seven years in Europe, from Ireland and England to the Balkans and Mediterranean. He holds an MPhil in Byzantine Studies (University of Oxford, 1999), and has published articles and books widely with major global publishers. He manages a Substack on travel, history, and literature, and is engaged in writing a series of detective novels set in the Eastern Mediterranean at the turn of the 21stcentury.