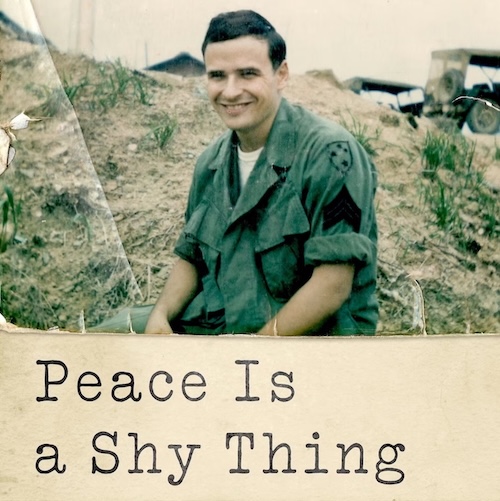

Peace is a Shy Thing: The Life and Art of Tim O’Brien

By Alex Vernon

St. Martin’s Press, 2025

Tim O’Brien’s thirteen-month deployment to Vietnam produced The Things They Carried, his indelible literary response to the war. He was a college student from Worthington, Minnesota, who opposed the war when he was drafted in the summer of 1968. He tried to desert but couldn’t go through with it, paralyzed not just by the fear of death or mutilation but by the prospect of social censure. “It was easy to imagine people sitting around a table down at the old Gobbler Café on Main Street,” he writes, “coffee cups poised, the conversation slowly zeroing in on the young O’Brien kid, how the damned sissy had taken off for Canada.”

In February 1969, he arrived at Chu Lai, his unit’s base in Vietnam. In March 1970, he returned to McChord Air Base in Washington state. O’Brien, who is now seventy-nine, has carried those thirteen months with ever him since, just as the US infantrymen whose wartime experiences he wrote about carried their steel helmets or iodine packets or condoms or letters from girls who didn’t love them.

Those thirteen months were a well of inspiration from which O’Brien drew again and again, as Alex Vernon illustrates in his new biography of the author, Peace Is a Shy Thing: The Life and Art of Tim O’Brien (St. Martin’s Press). The first biography of O’Brien, it’s a thorough and revealing disentanglement of the historical events that O’Brien reconceived in order to write his stories. In the process, Vernon’s book becomes a valuable window into the ways O’Brien metabolized life into art.

O’Brien’s writing on the Vietnam War derives its power from its extreme focus. Besides The Things They Carried (1990)—a staple of American high school classrooms and the undoubted pinnacle of his output on Vietnam—his major war books include the memoir If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home (1973) and the novel Going After Cacciato (1978). In these works, O’Brien applies his remarkable powers of observation with a focus as narrow as the booby-trapped Viet Cong tunnels in which many American soldiers lost their lives. O’Brien is one of literature’s keenest observers of the inner lives of infantryman drafted into an unjust war.

He decides to barely make contact with anything else: women of all nationalities, especially American women, who weren’t drafted; Vietnamese people, whether civilians or soldiers for the South or North; the American officers ranked slightly above the ones with whom he dealt directly; the political and social maneuvering that put the war in motion; ideological questions of containment, capitalism, and Communism. The focus of his writing has the effect of bringing the reader as close as imaginable to the experience of a grunt: a vulnerable cog in a vast, cruel, blind, and clumsy machine.

In a 2018 essay for The New York Times, the author and law professor Lan Cao identifies this as a weakness of the American response to Vietnam in general, while singling out O’Brien. “In The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien tells the interrelated stories of men from a single platoon and the things they took to war, down to the smallest details. . . . Encounters with the Vietnamese were barely worth a nod, and as far as allied Vietnamese soldiers were concerned, they were pithily dismissed by the narrator as ‘useless,’” she writes.

But Peace Is a Shy Thing shows that this was an aesthetic choice, not a moral failing. O’Brien the person is interested in the history and suffering of Vietnamese people and respectful of their interiority. O’Brien the author wrote what he knew. His Vietnam books are intentionally claustrophobic: there is a void where everything that exists outside the platoon is supposed to be. In theory, we know how brutal anti-insurgencies bring decent people to the dehumanization of others. O’Brien’s work forces us to feel the yawning absence of these others.

Cao’s criticism could more fairly be applied to Peace Is a Shy Thing. The biography is an impressive feat of research and reporting and gives valuable insight into O’Brien’s artistic process. But it makes the mistake of reproducing O’Brien’s extreme focus, giving the reader insufficient insight into the political, historical, or social context that formed the crucible in which O’Brien spent those formative thirteen months. That’s a shame, because Vernon could have helped his readers—especially younger ones who didn’t live through the period of the Vietnam War but recognize its contours of cruelty in Iraq or Palestine—to understand how decent men like O’Brien became so profoundly alienated from the people on whose part they were ostensibly fighting. In fiction, focus can be a virtue, even up to the very edge of solipsism. In a work of biography like Peace Is a Shy Thing, such a tight focus comes off as excessive and often reads like willful blindness.

In Going After Cacciato, a soldier deserts his unit with the intention of walking all the way from Vietnam to Paris. His comrades give chase, their journey becoming progressively more fanciful. Near the beginning, the narrator, Paul Berlin, meets a Vietnamese refugee named Sarkin Aung Wan. They begin a bloodless kind of romance in which Wan remains a profoundly elusive figure, down to such basics as her age. In this novel, she isn’t a real character and isn’t meant to be. Instead, she is a projection of the soldiers’ incomprehension of the Vietnamese, a symbol of the way war heightens the omnipresent unbridgeable gap between people. “Emotions and beliefs and attitudes, motives and aims, hopes—these were unknown to the men in Alpha Company, and [the people of] Quang Ngai told nothing,” O’Brien writes in the novel. “‘Fuckin’ beasties,’” says Stink, one of O’Brien’s characters, mimicking “the frenzied village speech. ‘No shit, I seen hamsters with more feelings.’”

Paul Berlin gets closer to Wan, but he never really comes to understand her. The war has robbed him of the ability to fully read people who are very different from him. And the experience is mutual: for a much longer time than necessary, Wan calls Berlin not by his name but by his rank, Spec Four. All the things O’Brien says the soldiers do not know about the Vietnamese—their “emotions and beliefs and attitudes, motives and aims, hopes”—are all the things an author needs to imagine when he wants to write a well-rounded character. Even the structure of the phrase mirrors the soldier’s diminishing interest in Vietnamese people: first three nouns, then two—one. In other words, O’Brien is aware of this but chooses to leave Wan a cipher because his focus is on the soldiers who remain walled off from people like her.

Such mimetic effects are hard to pull off in non-fiction. In Peace Is a Shy Thing, Vernon seems to replicate the indifference of O’Brien’s characters toward imaginary women with something similar toward a real woman. In 1990, O’Brien had an affair and left his wife shortly thereafter. Vernon promptly dispatches with Ann O’Brien, the author’s wife and partner of nearly twenty years, in just a few lines:

Ann had confronted him in the car about his emotional absence: You’re always distracted. If you don’t want to be with me, move out. It was all he needed. That very day O’Brien drove to his old neighborhood with a carload of essentials, found a building at the corner of Massachusetts and Chauncy, and asked the super to call the landlord. He signed the lease on the spot that night.

Perhaps that is how the end of the long relationship felt to O’Brien. But how did it feel to Ann? A biography is less dependent on the ruthless forward thrust that fiction requires. Vernon would have done well to linger with her feelings, which should have been possible even had she decided not to talk to him.

Vernon’s biography also reproduces O’Brien’s fictive indifference to the political context of the Vietnam War. This indifference is a powerful aspect of O’Brien’s writing. In If I Die In a Combat Zone, O’Brien invents a stunning comparison for war’s illogic:

Men are killed, dead human beings are heavy and awkward to carry, things smell different in Vietnam, soldiers are afraid and often brave, drill sergeants are boors, some men think the war is proper and just and others don’t and most don’t care. Is that the stuff for a morality lesson, even for a theme?

Do dreams offer lessons? Do nightmares have themes, do we awaken and analyze them and live our lives and advise others as a result?

For an infantryman, finding a lesson in war is like drawing rules for living from a nightmare. The comparison is instantly clear and emotionally honest. But it doesn’t absolve Vernon from examining the political context that made this particular war so nightmarish. Not all wars have felt as cruelly pointless as Vietnam—so what made this conflict different? Why was the sense of moral injury that Vernon rightly identifies as the core of O’Brien’s writing so prevalent especially among Vietnam veterans? This biography doesn’t help us understand.

That’s a missed opportunity, because Vernon, a West Point graduate, a combat veteran of the first Gulf War, and an English professor, certainly has insight into these questions. He’s also a gifted researcher who could have done great work describing the war’s history. A section on the nonfictional events behind a fantastical-sounding chapter from The Things They Carried shows his skill. The story, in which a soldier’s teenage girlfriend arrives in Vietnam to spend a few weeks with her sweetheart but takes to soldiering with a terrifying verve—she falls in with the Green Berets and takes to wearing a necklace of human tongues—sounds fanciful. Vernon shows that it was based, however loosely, on fact. In war stories, O’Brien writes in The Things They Carried, “there is always that surreal seemingness, which makes the story seem untrue, but which in fact represents the hard and exact truth as it seemed.” Vernon does well to capture this.

Vernon is excellent at showing the process of experience becoming art. The author Teju Cole has said, “When you’re doing fiction you give to the character something one or two steps to the side of what is your own core. Fiction works through all those distances.” Vernon untangles how O’Brien the soldier, in love with a faraway girl who didn’t love him back, recited an Auden poem to himself as he trudged through the jungle. In The Things They Carried, this poem becomes a pebble O’Brien’s character “carried in his mouth, turning it with his tongue.” It’s a memorable example of an artist smoothing a biographical detail into hardened emotional truth.

For a writer clearly possessed of deep insight into O’Brien’s work, it’s disappointing when Vernon sidesteps the opportunity to do literary criticism of his own. Describing a bad review in The New York Times of a later O’Brien novel, Vernon writes that “Maybe The Nuclear Age is simply a mediocre novel with an angsty protagonist not nearly as appealing as Huck Finn and Holden Caulfield.” Coming from a writer who by now knows O’Brien’s writing better than almost anyone—certainly better than a contemporaneous reviewer in the Times—that reads like a cop-out.

Vernon’s approach to detail and texture is hit or miss. The impact of his chapter on the real story behind “Sweetheart of the Sông Krông Nô” is blunted somewhat by labored, invented dialogue. (“I wonder how he pulled that off.” “Guess it can’t be too hard. Just balls and brains. Balls and brains.”) He squanders the biographer’s “must haves”—the conditionals which are essential when trying to enter another person’s brain, but should be used sparingly—on unimportant details. He speculates that O’Brien and his editor might have had “a pupu platter and some Navy Grogs” after the completion of The Things They Carried. He tells us what music was played at Ann O’Brien’s sister’s wedding (Pachelbel’s “Canon”). A house O’Brien bought in Texas “had previously been owned by Jimmie Connolly, one of the founders of the golf club. His last day in the home, Connolly sat forlorn, looking at the back window at his course.” (Connolly is not a character who reappears.) Although important parts of the biography seem too informed by O’Brien’s aesthetically productive solipsism, these less essential details could have used the fiction writer’s more brutal red pen.

Despite its flaws, Peace Is a Shy Thing is a valuable document about an important artist and the ways his experiences in peace and war shaped his writing. Well-versed in O’Brien’s full personality, it succeeds in the primary aim of any artist biography: to show the sparks that caught flame in the art.

Still, it would have been served by a wider view. Politics create the conditions in which American soldiers do immoral things, like summarily executing people in boats in the Caribbean. Some of those soldiers will experience the same moral injury O’Brien turned into great art. What if we found a way to stop subjecting soldiers to those violations on our behalf? A long shot, but one that would mean we have finally found the lesson in the nightmare.

Jeffrey Arlo Brown

Jeffrey Arlo Brown is a journalist based in Berlin. He has been an editor at the classical music magazine VAN since 2015. As a freelance writer, his work has appeared in The Baffler, The New York Times, Slate, Noema Magazine, Narratively, Atlas Obscura, TAZ am Wochenende, and other outlets. His first book, a biography of the composer Gérard Grisey, was published by the University of Rochester Press in 2023. He is currently translating a memoir by the composer Georg Friedrich Haas.