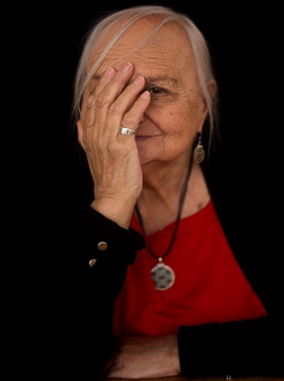

Photo of Svitlana in Berlin by Morris Weiss

Author’s Note: The core of this article was based on interviews with Svitlana Petrovskaya, a ninety-year-old Ukrainian woman currently living in Berlin. We had access to her collection of personal letters and memorabilia, including publications about her. All photos are courtesy of Svitlana unless noted.

* * *

A Berlin Apartment: Summer, 2024

Svitlana Petrovskaya remembered blocking out the pain. She had endured much worse than chronic arthritis and a back injury over the course of her life. Instead, she focused on the faded photograph she held in her hands. Her diminished eyesight was enough to make out the image of a former student dressed in an early nineteenth century military uniform. Oleg, like many of her other students, had been part of an after-school theatre group she directed at Klovsky Lyceum #77 in Kyiv. Each of those students triggered bittersweet memories.

Svitlana’s students loved her, and she in turn had stayed in touch with many of them over the more than fifty years of teaching at the school. Oleg was one of those students, but he had died in combat after serving two tours of duty for the Ukrainian army. All that remained of him resided in the faded photograph, along with other photographs from her teaching days, some of which included students who had been killed in the Russian invasion of 2022.

Photo of Oleg (1980) by Victor Popov

Photo of Oleg (1980) by Victor Popov

Svitlana put Oleg’s photograph back on her bookshelf. An international group of children from a local summer camp was waiting for her in downtown Berlin. Her memories of her students and the children she was about to meet hinting at a life that had been dedicated to helping the most vulnerable.

This is her story.

Bomb Shelter, Kyiv: February 2022

People rushed by the woman sitting on the Kyiv sidewalk. Most might not have noticed her presence, or if they did, mistaken her for a homeless person.

Svitlana outside bomb shelter in Kyiv | Zaborona Independent Media

Svitlana outside bomb shelter in Kyiv | Zaborona Independent Media

Kyiv’s residents didn’t linger on the streets after the full-scale Russian invasion. Air raid sirens warned of artillery and missile attacks that were coming closer to the city.

Like many Kyiv residents, Svitlana had sought safety in one of the repurposed bomb shelters across the city. Now she sat against the wall of a former school building. In the basement below the school, the shelter was crammed with families and people of all ages.

On this day she needed to be outside, not to get fresh air, but to send a message to history teachers in Russia. As she leaned her walking sticks against the wall, she waited for the film crew from Zaborona, the Ukrainian independent news channel, to signal her to begin speaking. Well known, both inside Ukraine and in much of Russia among educators as an exemplary teacher, she felt her words might carry some power. What she had to say would be seen by thousands of Ukrainians and Russians in this YouTube video message:

Please don’t let your children come here! Don’t let them kill our Ukrainian children and women. . . . Stop this war. Then, during the Patriotic War (World War II), we were able to stop the fascists together. We can do this now with your help. Help Ukraine!

Save your children! Take to the streets! Write petitions! Demand that the government immediately end the war. We believe in you! We count on you! We are waiting for your actions!

Svitlana and many Ukrainians shared the hope that a critical mass of the Russian people would rise up in protest. It never happened.

In the next days, the sounds of war became louder. Fear spread like a contagion in the bomb shelter. People muttered in hushed tones, “The Russians are about to enter the city.”

Those who could began leaving the bomb shelter to join relatives outside of Kyiv. Svitlana’s friends convinced her to leave the country because of her physical condition. When it was time to evacuate, she boarded a Budapest bound bus packed with women and children. As the bus pulled away from the station, she wondered if she would see Ukraine again. For the second time in her life, she would become a refugee. Her mind went back to the day when she fled the Nazi invasion of Ukraine.

Voyage to Kinel-Cherkassy, Russia: July 1941

Six-year-old Svitlana huddled between her older sister Lydia and her mother Rosa. They were squeezed next to other mothers and children on an open-air truck ready to leave Kiev (Kiev was legally renamed Kyiv after Ukraine’s independence from Russia). In June the Wehrmacht surprised the Soviet Union when they crossed the border in western Ukraine and began the first phases of what would be known as Operation Barbarossa. It was only a matter of months before they entered Kiev.

Their father, Vasily, a soldier in the Red Army, had arranged for a truck to evacuate them and other families. Hope for survival seemed to point east, toward the heart of the USSR. As the old Soviet truck lumbered out of the city, Svitlana said, “I knew I would be safe with my mother. She always protected children.” Rosa had been a respected teacher and principal at a school for the deaf community, just like Rosa’s parents had been.

With the Wehrmacht close on their heels, the truck finally crossed the border into Russia. Some of the Kiev women and children got off there, but Rosa and her daughters transferred to a cattle train heading deeper into Russia. She had heard from one of the women along the way that the village of Kinel-Cherkassy was a safe place for refugees.

Svitlana, Rosa, and Lydia eventually reached Kinel-Cherkassy. Two months had gone by since their evacuation from Kiev. Exhausted from the ordeal Svitlana and Lydia waited outside a refugee processing center while Rosa filled out a questionnaire about her professional background. The very next day, Rosa was told she would be employed as a principal at a new school that was opening up in the village. That decision would mark another dramatic turn in Svitlana’s life.

“Not a Single Child Shall Die,” Soviet ‘Orphanage’: 1941-1944

There were strings attached to Rosa’s new assignment. The new school was to serve two hundred refugee children from Leningrad. The Secretary of the local Communist Party made it very clear to Rosa that the children were highly valued and that “not a single child should die under your care.” The consequences of a child dying were not spelled out, but the meaning was clear enough in Stalin’s Russia.

Thus, Svitlana’s first rigorous school experience in a makeshift academy began while some of the bloodiest battles of World War II were fought less than a hundred miles away. In her music class she fell in love with the recordings of some of the great pianists and classical violinists of Europe. Practicing ballet while listening to Chopin enabled her to feel free and happy, psychologically buffered from the misery of warfare enveloping Europe and Russia. To this day she still remembers how Chopin’s Nocturnes transported her to a place of melodic refuge.

While Svitlana immersed herself in ballet and music, Rosa spent her days traveling to towns and military regiments begging for food and supplies for the school. Svitlana remembered with pride that “None of the children from the orphanage died under my mother’s care during the time we lived in Kinel-Cherkassy.”

In 1943, though, there was one death that devastated her. After the Soviet army liberated Kiev, a letter arrived from a relative. It stated that Svitlana’s grandmother and one of her daughters had been murdered in September 1941. The SS led Einsatzgruppen shot them and threw their bodies into the Babi Yar ravine outside of Kiev. Nearly thirty-four thousand other Jews were murdered in two days at that ravine. In the years to come, the pain of Babi Yar would dig ever deeper into her consciousness.

Palace of Hope, Life of Loss—Post-War Kiev: 1945-1948

By the summer of 1945, a year had gone by since their return to Kiev. The war was over, but the devastation in the city would last for years. With the help of Rosa’s brother, they found an apartment close to the Maidan, the central square in the city.

Rosa got a job teaching at a school for deaf children. Svitlana and Lydia enrolled in School #79, an all-girl’s school. Svitlana remembered that “the school offered free breakfasts for girls who lost their fathers in the war and whose families lived in poverty.” The meals were mostly hot potatoes and donuts, but they were a comfort during a time of chronic food shortages.

Months later Rosa received a letter from a Russian military doctor working in an Austrian hospital. The letter stated that Vasily had been captured by the Nazis in 1941. Until the end of the war he had been moved from one concentration camp to another. Finally, in May of 1945 he was liberated from the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. While Vasily was freed, his joy was short-lived. Soviet authorities arrested him and thousands of other Red Army prisoners as “traitors” because according to Stalin “true” Russian soldiers would never surrender in battle.

The NKVD (Soviet secret police from 1934 to 1946) transferred him to a “filtration camp” outside of Kiev. He was given one hour to see his family before being taken away into the vast GULAG system of Stalin’s Russia. Svitlana was alone when he knocked on their apartment door. “I didn’t recognize him. He looked like a ghost and barely spoke.” She remembered little else from her short time with him.

As the months wore on, Svitlana’s love for ballet intensified but so did the arthritic pain in her legs. By the time she was an adolescent she realized her dreams of becoming a ballerina were not to be. Dancing no longer brought the same kind of escape, only more excruciating pain.

Another career path in life began to emerge at this time. It was first manifested in her work with younger children in the Young Pioneers Club, a Soviet youth organization for creative work, sports, and ideological indoctrination. For Svitlana, the Young Pioneers’ Communist Party ideology held no allure for her. Rather, it was an arena where she could help younger children cope with the emotional ups and downs of the world around them.

Svitlana (far right, first row) in Grade 8 as a Young Pioneer mentor for Grade 4 children

Svitlana (far right, first row) in Grade 8 as a Young Pioneer mentor for Grade 4 children

Svitlana also recounted a traumatic incident that occurred during her years as a Young Pioneer and high school student. One day in her history class, five students arrived two minutes late for class because of delays in the school cafeteria. The teacher humiliated them in front of the class saying, “These so-called starving children finally decided to show up.” One of the girls singled out was Svitlana’s close friend who had lost five of her brothers in the war. The teacher’s body language exuded contempt toward the girls. Svitlana said, “That was the first time in my life I felt a deep, burning anger and didn’t know what to do. I was silent, frozen. I had loved that teacher, but at that moment she became a monster to me. I promised myself if I became a teacher, I would never treat children the way she did.”

Enemies of the People—Soviet Ukraine: 1950s & 60s

After graduating from high school Svetlana entered Kiev State University. Up until her last years in university, Svitlana’s focus was to become a teacher who treated all her students with respect. That quality would always be there, but until she met Miron Petrovsky in 1955 she had not questioned the very foundations of the Soviet system. Miron was a writer and literary critic who eventually married Svitlana. He introduced her to a vibrant circle of Ukrainian dissident poets, writers, and philosophers in the 1950s and 1960s.

This exposure to the works of banned or non-sanctioned Ukrainian and Russian writers and artists brought with it danger. Miron knew this full well. In 1959 someone reported Miron to the police, saying he was reading Boris Pasternak, who was banned from publishing his works in the Soviet Union. The KGB searched Miron’s apartment and found a small book of Pasternak’s poems. This led to a twenty-year ban on Miron being able to publish his own writing, and it also prevented him from holding any official position in a university or the government.

Life was not easy for Svitlana and Miron during these years. After their marriage in 1961 they had a baby boy, Ivan, the next year. With Miron banned from gainful employment and Svitlana’s meager high school teacher’s salary, paying bills and feeding a new family was a daily struggle.

From the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s Khruschev’s “political spring” provided a temporary respite from Stalin’s iron grip on independent cultural production. Some dissident prose and poetry could now be published.

In 1966 Svitlana experienced her own kind of intellectual spring when she, Miron, and their son spent the summer in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (now the independent country of Moldova). They rented a cheap cottage in a small village with one grocery store. There were very few food items in the store, but there were plenty of low-cost books that had been previously unavailable in Soviet Ukraine. She read about new pedagogical ideas that focused on a more humane ad student-centered learning, an approach that was absent from Soviet era schooling in Ukraine. This discovery would have a momentous impact on Svitlana.

When Svitlana returned to Kiev, she resumed her high school teaching with a new passion. While Svitlana’s intellectual spring was just beginning, the Soviet spring came to a crashing end in 1968 when Russian tanks rolled into Prague. As a form of protest against the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia, Jan Palach, a student at Prague’s Charles University, set himself on fire. His suicide became an international symbol of what totalitarian repression could do to the soul of its people.

Mass gathering in Prague commemorating Jan Palach’s Death (1969) | Radio Free Europe Archive

Mass gathering in Prague commemorating Jan Palach’s Death (1969) | Radio Free Europe Archive

Palach’s death and the Russian repression of independent thought and creative expression shocked Svitlana. This time it brought her to tears when she discussed the events with her history students. For weeks she felt nearly paralyzed with inertia. Miron encouraged her to seek psychiatric help. The doctor she saw didn’t just treat her; she warned Svitlana, “Don’t you know you live in a fascist state? The doctor then told me that I risked imprisonment if I continued to discuss the events in Czechoslovakia with my students. She convinced me to take a leave from teaching for several months and receive treatment at the hospital.”

When Svitlana returned to the school, she decided not to teach the history of the second half of the twentieth century. Instead, she switched to teaching English to primary school students. If she could not discuss ideas that cast doubt on the state’s official narratives, she would not teach at all about the world her students were living through.

From Silence to Activism—Steps Toward an Independent Ukraine

Breaking her paralysis from speaking out and her teaching of history changed for Svitlana in the 1980s. That was the time of Perestroika, Mikhail Gorbachev’s reform of traditional Soviet policies. There was a new opening for Ukrainian writers and artists to publish and discuss previously forbidden topics such as human rights and Ukrainian national identity. This was the spark that Svitlana needed.

She began teaching modern history again. Svitlana encouraged her students to explore and question Kremlin approved accounts of Soviet history. By the time Ukraine gained its independence from Russia in 1991, Svitlana had begun a museum dedicated to the life and philosophy of the pediatrician Janusz Korczak. He and the Jewish children under his care had been murdered at Treblinka, the Nazi death camp. Svitlana’s museum and Korczak’s pedagogy of “love the child” inspired her students to accompany her to local children’s hospitals. These hospitals were plagued by shortages of many basic necessities. Her students brought the children fruit, milk, and bread to supplement their meagre diets. They also provided informal school lessons for the children.

Svitlana also started a school history museum that focused on the human costs of war. Plenty of Soviet-era secondary schools had museums that glorified Russian military victories and heroism. Her museum did something else. As she told a Latvian reporter, “All Soviet propaganda made the message that we were winners. The price of so-called victory faded into the background.” Instead, she brought in personal accounts and poetry from soldiers who had been traumatized or lost their lives.

She explained, “Our museum was honest. It was also about what our students experienced. This is the truth about war. A museum with their faces facing us.” The words, “faces facing us,” had a powerful resonance for the students in Lyceum #77. Some of the school’s former students had died in the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, as well as during the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine. By using some of their letters, she was able to infuse an emotional and ethical dimension into students’ understanding of war’s costs.

Photo of Oleg (foreground) on the front lines before his death | Photo from Oleg’s Facebook Page

Photo of Oleg (foreground) on the front lines before his death | Photo from Oleg’s Facebook Page

Svitlana’s pedagogical activism had moved into the community and was reborn alongside the post-independence nationalism of Ukraine itself. In 2013 thousands of protesters stormed the Maidan Plaza. They came to denounce the growing influence of Russian oligarchs in Ukrainian politics, widespread government corruption, and the President Viktor Yanukovych’s broken promise to make a free trade agreement with the European Union. Svitlana and her students were out every day bringing food and water for young and old who remained camped out for ninety-three days until Yanukovych was forced out of office.

2014 Protesters on the Maidan | Reuters/Gleb Garanich

2014 Protesters on the Maidan | Reuters/Gleb Garanich

Before she retired from teaching, she also helped found the Ukrainian chapter of Memorial, a Russian-based human rights organization that was banned by Putin in 2022. Svitlana told us, “Together with my students we searched for the lives of those who were arrested and ‘disappeared’ during the Stalinist repressions.”

Journey to Budapest, Vienna, and Berlin: 2022

The bus took more than twenty-two hours to cross the border into Hungary. Svitlana looked around at her fellow passengers, women and children, crammed together. She recounted, “There was a young mother next to me who had a four-day old baby who cried all the time.” The baby’s tears and the faces of the other children on the bus brought back childhood memories of her flight from Kiev in 1941.

When they arrived in Budapest, Svitlana didn’t know what to expect. It was supposed to be a stopover for her before she continued her journey to Vienna and finally to Berlin where her daughter, Katya, would meet her. For the rest of the passengers, Budapest would be their last stop. She remembered saying to herself, “What would happen to the women and children?”

She found out the answer when the bus eventually pulled up to an emergency shelter. Everyone was confused, not knowing what came next. Many of the women had few clothes and little money. Svitlana recalled, “The children ran around crying and wanting to go home.”

Svitlana had her train ticket to Vienna, but she couldn’t leave without making sure the children were taken care of. Not knowing the language and being hobbled by her back pain and arthritis did not stop her. She first contacted the Hungarian Janusz Korczak Society. Volunteers from the society helped her organize clubs for the children and secure food and emergency supplies for the women on the bus.

On her own Svitlana managed to persuade the director of the local circus to provide free entry for the children. “Every day for two weeks I took the children to the circus as well as organized bus tours of the city for them. The children becoming calmer and more joyful.”

When Svitlana finally had to leave Budapest, the children begged her to stay. An older woman about to leave on another train saw the scene of the children hugging Svitlana. Svitlana remembered that the woman “silently took my hand to put a silver ring on my finger. The ring is still on my finger. I have never taken it off. The woman’s name was Irina, an old poet from Dnipro.”

At the Vienna station she noticed numerous humanitarian aid tables set up for Ukrainian refugees. One in particular caught her eye. Two young women wore face masks and had a sign in Ukrainian that read, Treat yourself to borscht. Svitlana found out that they were students from Taiwan who had volunteered to aid Ukrainian refugees in transit. To this day her eyes fill with tears remembering that day. “These young students wanted to warm us up with borscht but also with Ukrainian words. The Russians send their men to kill, but the Taiwanese girls, who never knew us, come to help us. They melted my heart.”

Svitlana eating borscht in the Vienna train station

Svitlana eating borscht in the Vienna train station

Coda

Berlin is not Svitlana’s home. Yet, she cannot go back to Ukraine, at least not now. Maybe never, given how the war grinds on.

Svitlana is attuned to the ongoing destruction of her own homeland. She told us, “My heart breaks with pain as I watch the news, recognizing familiar streets and buildings now reduced to rubble. It is unbearable for me to have experienced one war to witness this horror again.”

We wondered why she did not slip into a deep despair given these feelings. Svitlana told us she turned to Ukrainian poets for solace. In particular, she mentioned the life and work of dissident poet, Vasily Stus, who died in a Soviet labor camp in 1985. She said, “his poetry is full of unbroken resolve, moral resistance and spiritual freedom in the face of totalitarian oppression.”

Svitlana quoted one of his prison poems:

I am strong

I am invincible

I will endure everything

She then shared a line from a letter Vasily wrote in 1972 during his first imprisonment: “They can take everything away from a person except the ability to remain human.”

Svitlana concluded by mentioning one other poet who has meaning for every Ukrainian. She shared the words of the early Ukrainian feminist poet and activist, Lesya Ukrainka (1871-1913):

Без надії сподіваюсь!

Хочу жити! Геть, думи сумні!

(Without hope, yet I hope.

I want to live! Away, sorrowful thoughts!)

Photo of Svitlana today by Morris Weiss

Photo of Svitlana today by Morris Weiss

As a Russuan, living in the USA, I am shocked by President Trump still trying to support a criminal Putin, who continues that criminal war with Ukraine, Russia’s closest Slavic relative. Brothers kill brothers, and only because crazy Putin wants their former Soviet Empire.

My heart is crying for the Russian killing of the young (and not young) soldiers, and any people who died in that criminal war.

Mir —The World can only win if there were more people like Svitlana, who is now more than 90. I am very proud that people like Svitlana exist in this world and help others to survive.